Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Vibrations Power Vehicle’s Exhaust Filter

Materials Science: A car’s vibrations and exhaust flow generate charged surfaces inside a filter that captures air-polluting particulates in the exhaust

by Melissae Fellet

November 30, 2015

A car’s vibrations can power a new filter that captures air-polluting particles from the car’s exhaust (ACS Nano 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06327). The researchers plan to develop the filter for commercial use in diesel and gasoline-powered vehicles.

Vehicle exhaust contains particulates that are linked to heart and lung disease. Particles with diameters smaller than 2.5 µm, called PM2.5, are linked to the strongest health effects. To meet air quality regulations that restrict emissions of PM2.5, diesel vehicles have exhaust filters to capture these particles. However, typical filters that work by passing the exhaust through a porous material can lower engine performance and fuel efficiency. As particles gather and begin to plug the pores, they restrict the flow of exhaust gases through the filter, generating a back pressure that causes the engine to work harder and consume more fuel. Another type of filter contains charged surfaces that attract oppositely charged exhaust particles. Although less pressure builds up with these filters, they require electricity to generate the charged surfaces.

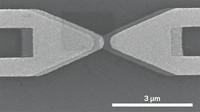

Zhong Lin Wang, of Georgia Institute of Technology and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his colleagues wanted to develop an electrostatic filter that collects particles without requiring external power. The researchers designed their new filter to operate using the triboelectric effect, which generates electricity when different material surfaces rub together and build up a static charge.

The new filter contains 2-mm-diameter polytetrafluoroethylene beads sandwiched between two aluminum electrodes, each slightly larger than a typical passport. First the researchers tested it in the lab, by measuring the charge built up as the filter jostled up and down. As the beads bounce between the two plates, they grab electrons from the metal as they make contact. As the beads fall away from the plates, the separation between the positively charged plates and the negatively charged beads generates a pair of electric fields between the layer of beads and the two plates. When the researchers sandwiched enough beads between the electrodes so that their surface area equaled that of the electrodes, the filter generated 3,000 V of potential difference between the two plates.

Next, the researchers attached the filter to the tailpipe of a gasoline-powered car and funneled the exhaust gases through the filter. The car’s vibrations and exhaust flow bounced the beads to create the electric fields. These fields attract charged particles in the exhaust, causing them to stick to the plates and beads inside the filter. Attached to the car, the filter removed about 95% of PM2.5. After 50 hours of operation, the collection efficiency for PM2.5 fell to about 82%.

In 2017, the Environmental Protection Agency will begin to implement stricter emissions standards that specify a 70% reduction in PM2.5 emissions from passenger cars. Adding particulate filters may be one way to reduce those emissions, says Greg Schroeder, an engineer at the Center for Automotive Research, in Ann Arbor, Mich.

André Boehman, a mechanical engineer at the University of Michigan, thinks this filter is an innovative way to reduce the fuel economy problems that typically impact engines with exhaust filters. For commercial applications, he adds, the filters would need to withstand thousands of miles of use in a variety of weather conditions.

Wang says they’ve now created a version of their filter that fits inside the tailpipe.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter