Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Neuroscience

Psychedelic compounds like ecstasy may be good for more than just a high

Scientists are testing whether drugs that alter consciousness can treat intractable mental health conditions

by Jyllian Kemsley

March 28, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 13

While studying alkaloid natural products and their derivatives, Sandoz chemist Albert Hofmann had to leave the lab early one day in 1943 because he’d accidentally been exposed to one of his products, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). As he wrote in his memoir, “LSD—My Problem Child,” he later reported to his department director: “I was forced to interrupt my work in the laboratory in the middle of the afternoon and proceed home, being affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed … I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.”

In brief

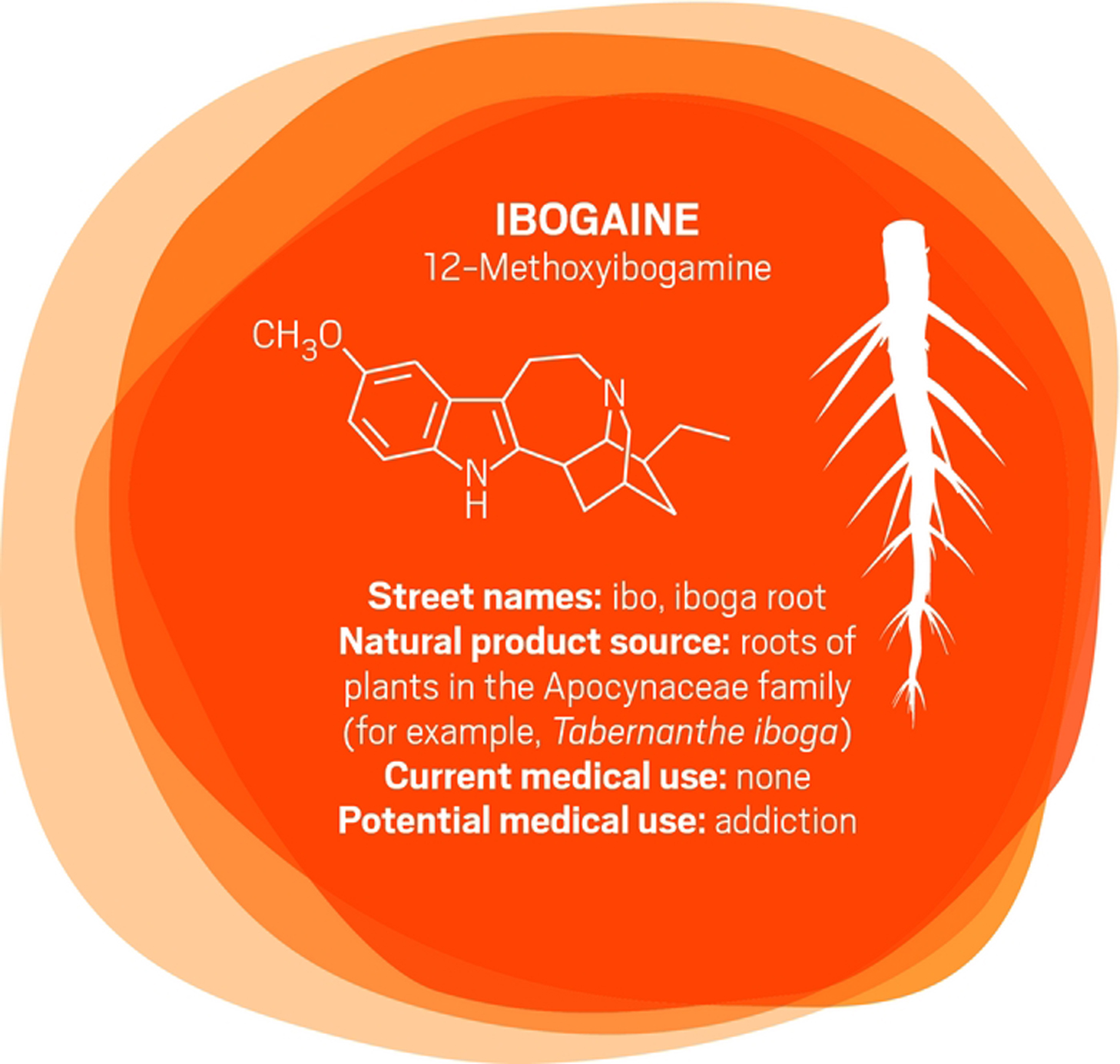

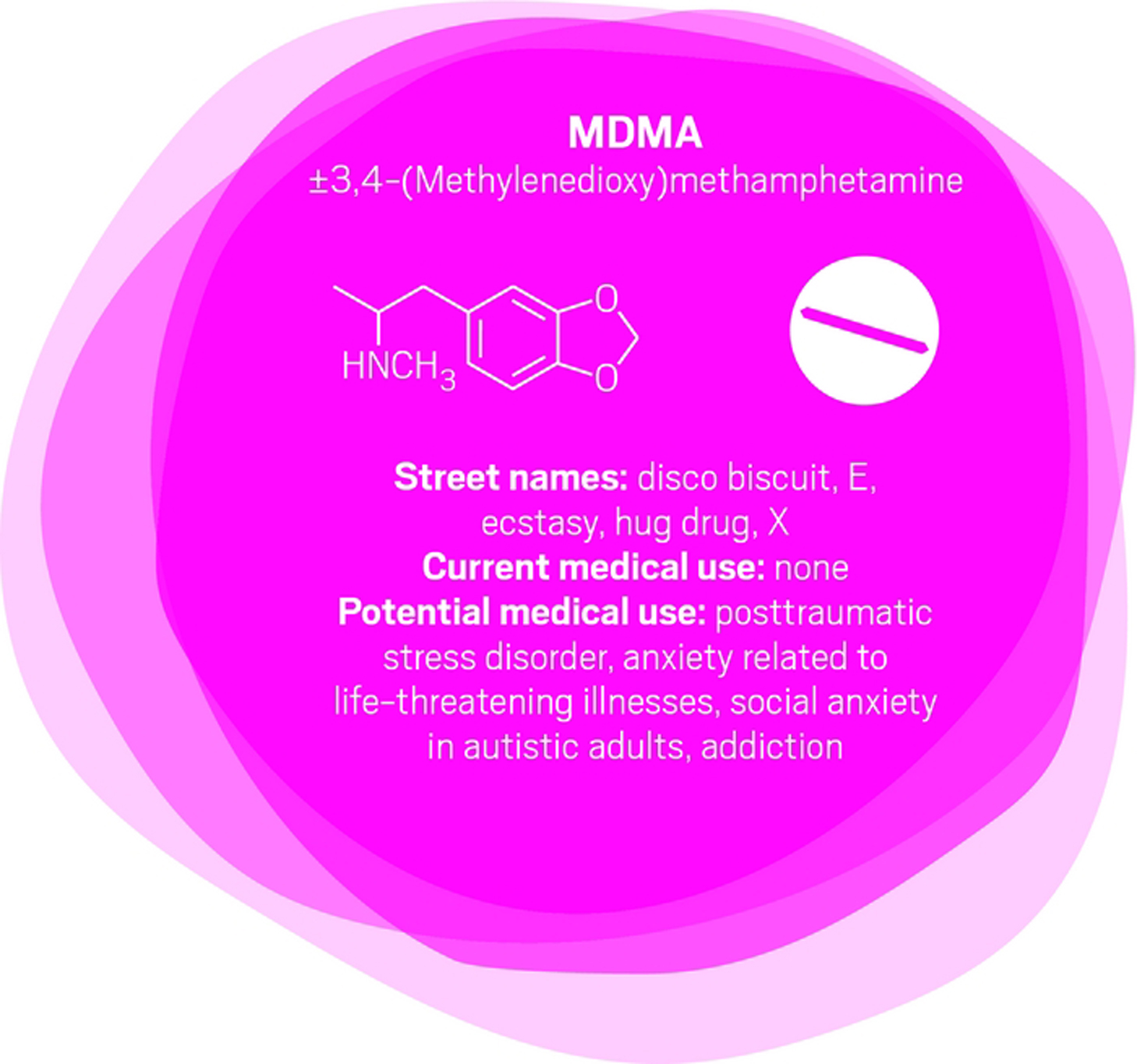

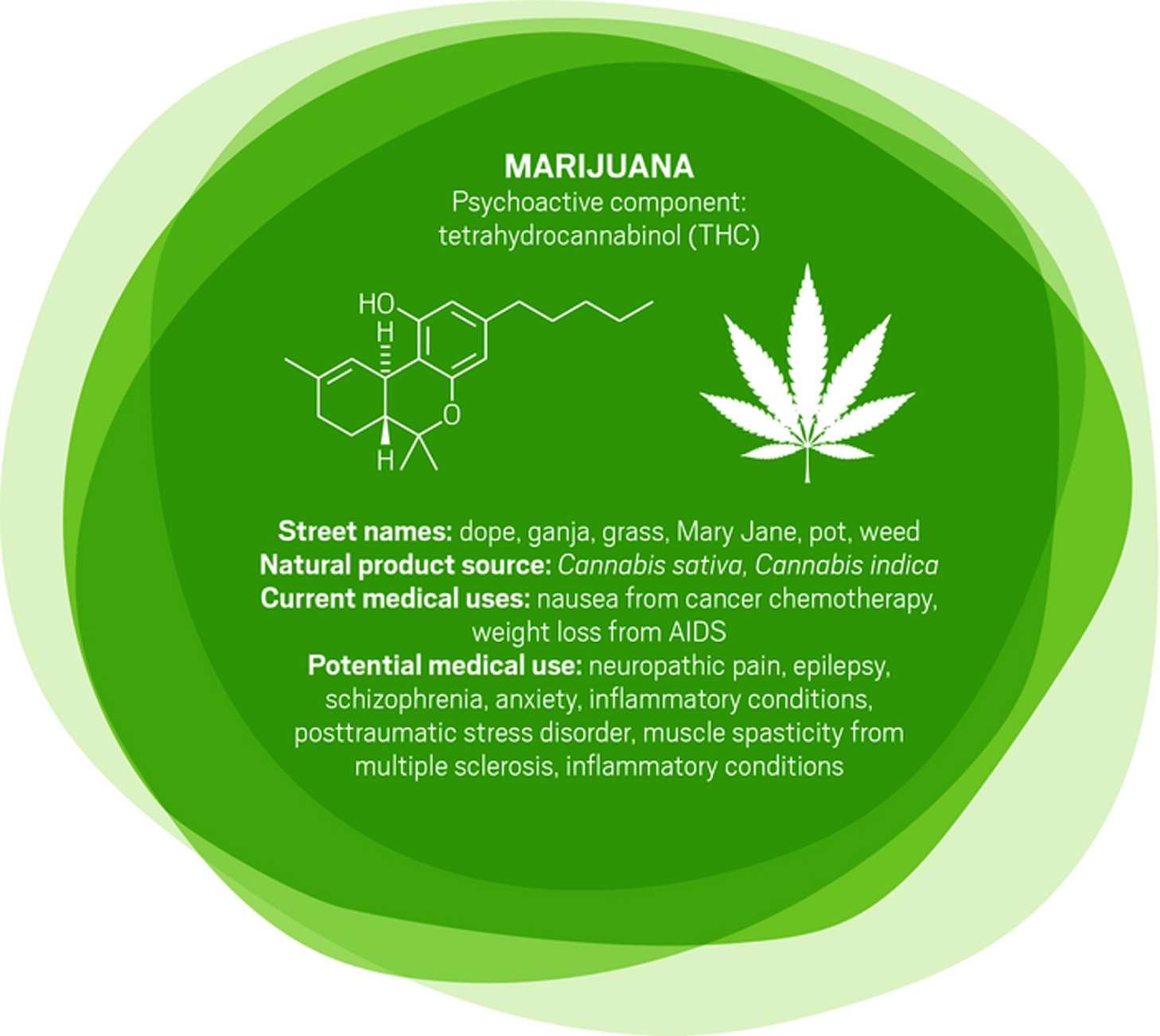

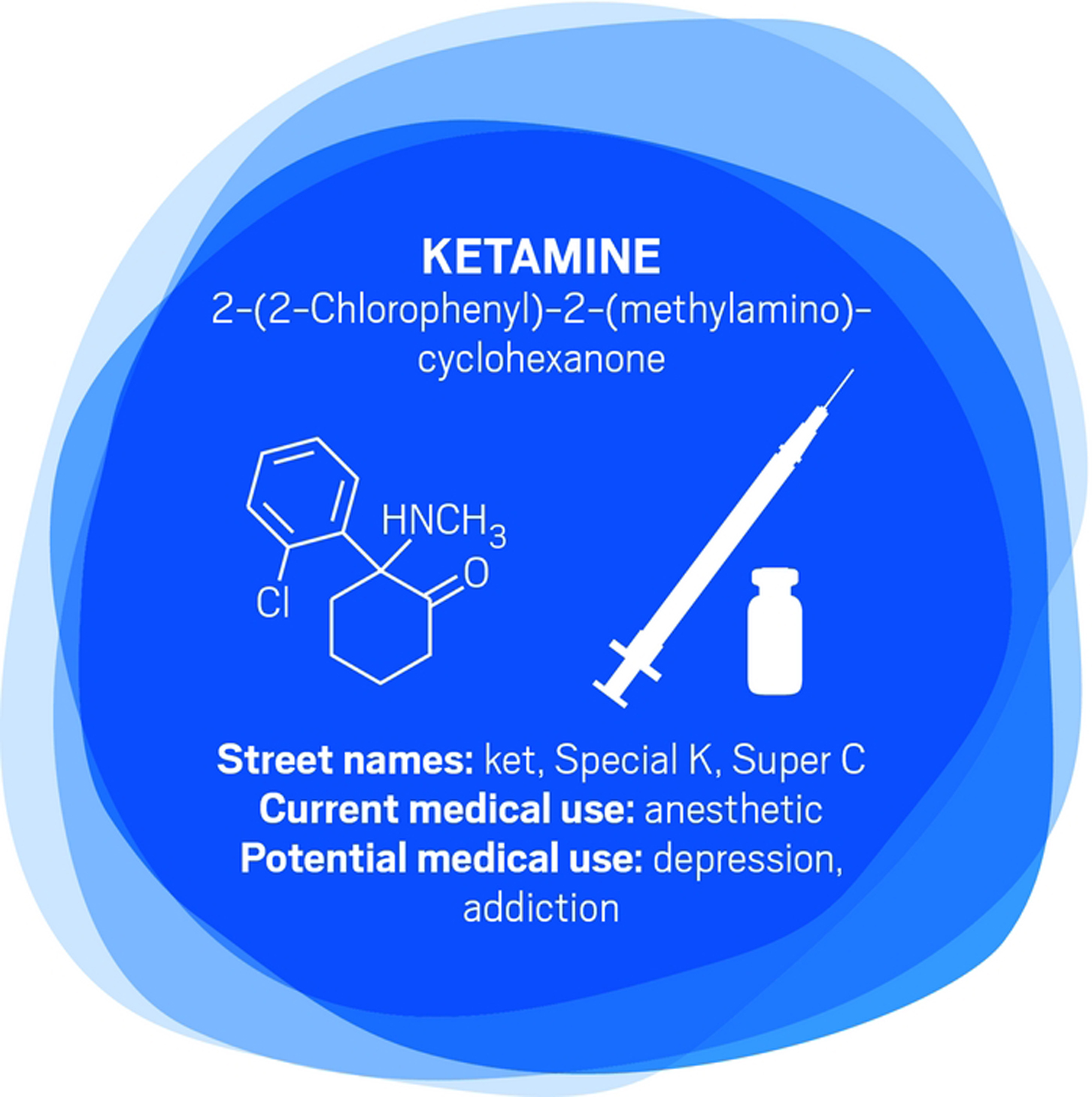

Conventional psychiatric and other therapies often fail to help people with mental health conditions. Some researchers are now turning to promising treatments from the 1950s and 1960s: psychedelic compounds that were largely banned in the 1970s as reaction to cultural and political turmoil linked to recreational drug use. Here, C&EN examines how ibogaine, MDMA, marijuana, ketamine, and psilocybin might be used clinically.

In the decades that followed, various researchers pursued LSD and other psychoactive compounds for medical uses, looking to use them to treat mental health disorders such as schizophrenia and depression.

Then the 1960s arrived, with the baby boom generation embracing an antiestablishment ethos as well as recreational drug use. Governments responded, in part, with the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, a United Nations treaty that led to bans on psychedelic compounds. “It was a reaction to cultural and political turmoil that was thought to be in some way tied in with youth culture getting involved in psychedelics,” says Charles Grob, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine and chief of child and adolescent psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. Contrary to scientific findings, the compounds were branded as having no medical use and a high potential for abuse.

Now, however, as clinicians find that conventional treatments for mental health conditions fail many patients, Grob and others have resumed research on psychedelics despite the barriers. With depression, for example, “there are some people that respond well to standard antidepressant medications but a lot of people who don’t, even through many trials of different medications and combinations of them,” says David Feifel, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. “There’s a big need for something more.”

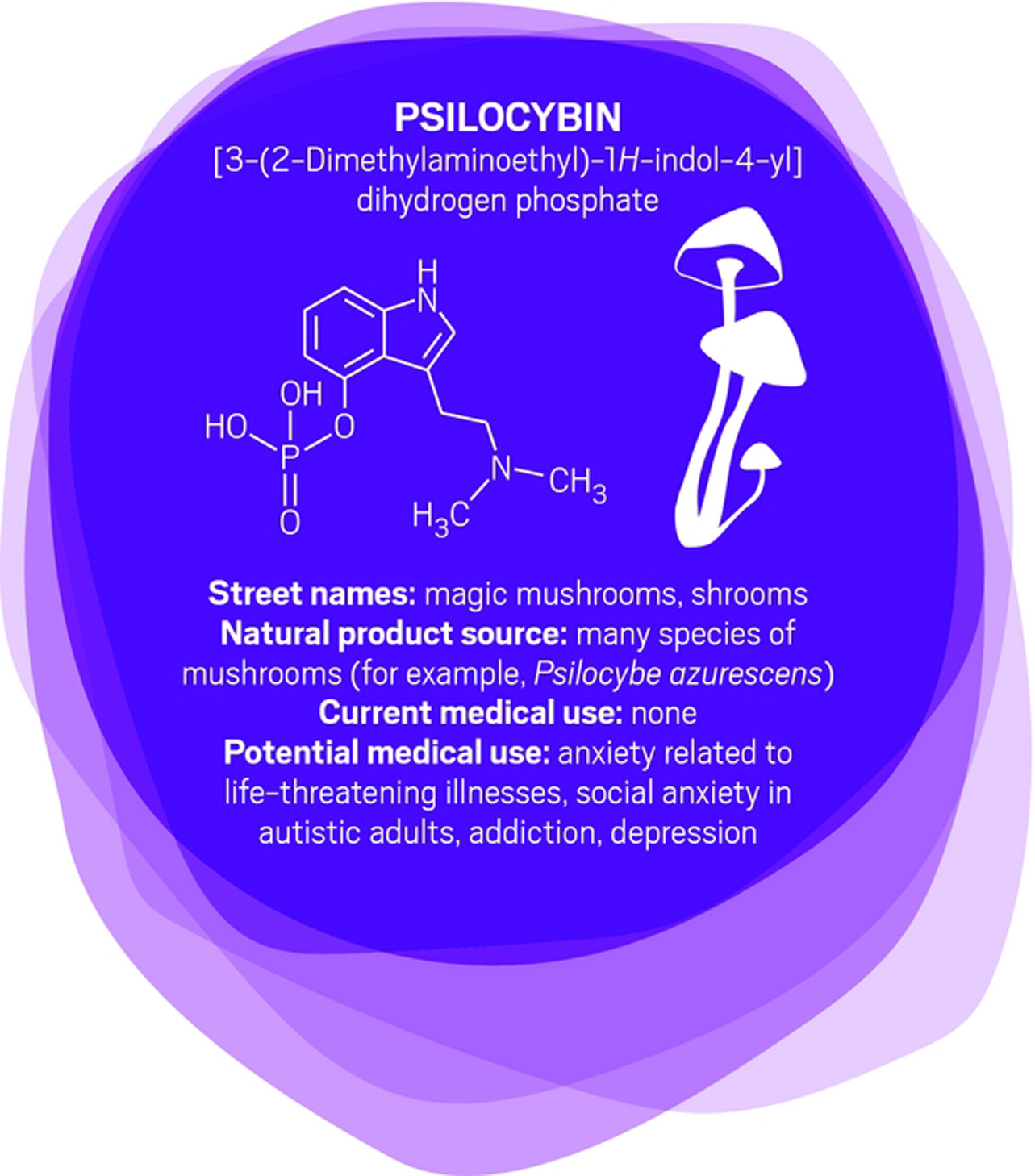

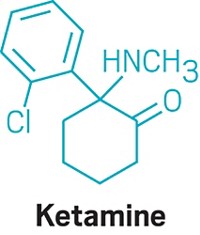

Feifel and other scientists are looking for that “something more” in compounds such as ibogaine, MDMA, ketamine, and psilocybin (the psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms). Researchers are also investigating beneficial uses for marijuana and its natural cannabinoids. Potential applications include treating addiction, posttraumatic stress disorder, neuropathic pain, epilepsy, and anxiety caused by diagnosis of a life-threatening illness such as cancer.

Research into using these compounds as medicines is in early stages, and the legal environment surrounding them makes studies difficult to conduct. U.S. researchers and their suppliers must obtain a special license from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Licensing requirements might include storing a drug supply in a safe that’s inside a room equipped with alarms, plus careful record keeping as compounds are dispensed to ensure none has gone missing.

Obtaining funding for clinical studies of psychedelics is also challenging. Pharmaceutical companies are generally uninterested in pursuing the compounds because their potential uses are already well-known, limiting companies’ ability to patent them and gain market exclusivity, says Rick Doblin, founder and executive director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which finances clinical trials. Donors to MAPS, which has a $3.5 million budget this year, include the social justice organizations Libra Foundation and RiverStyx Foundation, cleaning and personal care product manufacturer Dr. Bronner’s, the online community Reddit, and “aging baby boomers and tech millionaires,” Doblin says.

Then there is the societal concern that making psychedelic compounds available as pharmaceuticals will increase drug addiction and abuse. “I understand the concerns, but most classic psychedelics, such as psilocybin, don’t fit the conventional profile of a drug of abuse,” says Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University. He has spent most of his career funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse to study psychoactive compounds and the properties that make them addictive. He is also now running clinical trials using psilocybin to treat anxiety and depression in cancer patients.

The pharmacology of many psychedelics is different from opiates, which are highly addictive. People build up a tolerance to psychedelics that can’t be overcome with a higher dose, and they also don’t show withdrawal symptoms. What’s more, Griffiths says, the altered consciousness of a psychedelic trip can be “fantastically interesting” but also psychologically difficult to handle and unpredictable. He and others say that although their patients appreciate the psychedelic experiences, people don’t typically ask for more doses than necessary. Some of Feifel’s patients even postpone a repeat dose if they’re still doing well after the previous one.

As for adverse events, those are rare for pure drug material such as that used in clinical trials, researchers say. Negative reactions typically happen when people use recreational products that have been adulterated by questionable sellers.

That’s not to say that psychedelics are perfectly safe. As with all approved or potential pharmaceuticals, “we’re dealing with a cost-benefit analysis,” says Igor Grant, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and director of California’s Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research. “No drug is harmless. We need to really establish from a medical standpoint what the uses and limitations are.”

The following are several compounds being studied.

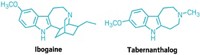

In the early 1990s, University of Miami neurology professor Deborah C. Mash traveled to Amsterdam to see ibogaine treatments firsthand. “A single dose of ibogaine could completely block the signs and symptoms of opiate withdrawal,” says Mash, who has spent her career studying the effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain. She and others are now studying ibogaine as a treatment for opiate, cocaine, alcohol, and nicotine addiction.

Ibogaine was first isolated in 1901. It interacts with glutamate receptors in the brain that are involved in learning, memory, and creation of new neural pathways. The receptor interactions are likely the source of ibogaine’s consciousness-altering effects.

But ibogaine is metabolized within 24 hours: A hydroxyl replaces ibogaine’s methoxy group, producing noribogaine. Noribogaine binds to serotonin transporter, opioid, and nicotinic receptors and is cleared from the body slowly. Consequently, noribogaine is likely the compound that’s responsible for reducing patients’ withdrawal symptoms and cravings over the long term, as well as the accompanying anxiety and depression (Neuropharmacology 2015, DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.032).

Mash has patented noribogaine and related compounds, as well as their formulations. She founded a company, DemeRx, to bring them into clinical treatment. DemeRx is currently running a Phase II clinical trial to evaluate noribogaine’s use as an alternative to methadone or Suboxone to help opioid addicts transition to sobriety in combination with support for behavioral changes.

Even if the noribogaine trials are successful, ibogaine could still have a role in addiction treatment because the “waking dream” experience it offers seems to help patients as well. “We work with people who have been hard-core addicts, abusing drugs and alcohol for more than a decade,” Mash says. As with other psychedelics, ibogaine induces an experience that patients report helps them gain insight into their destructive behaviors. That new awareness helps them be more open to therapy and lifestyle changes. “A combination protocol of a dose of ibogaine followed by noribogaine for maintenance could be optimal,” Mash says, “although more work is needed to determine whether that is the best approach.”

“After 100 years of modern psychiatry, our current best treatment for trauma-related disorders is only effective for 50% of people,” says U.K. psychiatrist Ben Sessa.

The cure for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is psychotherapy—talking through and processing the trauma with a mental health specialist. “About half of people will talk and, over weeks or months, will overcome their high level of distress and get better,” Sessa says. For others, talking about their experience is overwhelming. “They drop out of treatment and use dangerous drugs such as alcohol to mask their symptoms. They have high levels of self-harm and high levels of completed suicide,” Sessa says.

MDMA interacts with a transporter in the brain that causes the release of serotonin, which in turn causes the release of other neurotransmitters and hormones. For people who might otherwise flee psychotherapy, MDMA reduces fear and increases trust and empathy. MDMA is also mildly stimulating rather than sedating. The overall effect is to calm patients and help them engage with a therapist about difficult experiences. Sessa likens MDMA to a life jacket.

U.S. psychiatrist Michael Mithoefer leads clinical trials studying MDMA for PTSD. In an initial trial, Mithoefer and colleagues worked with patients who had PTSD for an average of 20 years, mostly from sexual trauma. The patients had undergone previous psychotherapy for an average of almost five years and were not helped by conventional antidepressants. They received MDMA or a placebo two to three times, with doses one month apart, as part of eight-hour sessions with two therapists followed by an overnight stay at the clinic for continued monitoring (J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, DOI: 10.1177/0269881110378371).

Going through the psychedelic experience, patients could focus inward and stay quiet as they wished or talk with the therapists. They also had extensive preparatory and follow-up psychotherapy sessions. Of 12 patients who received MDMA, 10 of them (83%) showed significant relief of their PTSD symptoms. In the placebo group, only two out of eight patients (25%) showed improvement with the same psychotherapy support.

Other studies show similar positive results, although “it is hard to have an effective ‘blind’ with this type of substance,” Mithoefer concedes, because patients can usually tell whether they’ve been given a placebo or the real thing.

Nevertheless, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies aims to start Phase III trials for PTSD next year, with MDMA synthesized by an unnamed U.K. contract manufacturing company following current Good Manufacturing Practices.

“There is a very, very broad range of medical conditions for which cannabis or its constituent chemicals could find applications,” says Daniele Piomelli, a professor of neuroscience and pharmacology at the University of California, Irvine. However, few good clinical studies have been completed.

Mammals naturally make some cannabinoids, including anandamide, which likely plays a role in stress response and social behavior, and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, which is involved in modulating activity at the brain’s nerve cell junctions.

Other cannabinoids, such as those produced in marijuana, can target the same neurological receptors as endogenous cannabinoids. Tetrahydrocannabinol is the one that generates a psychoactive response. It is already approved as dronabinol to treat nausea in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy and appetite loss in people with AIDS. “It’s a poor drug,” Piomelli says. It has poor bioavailability and has a complex metabolism, he adds.

Researchers are studying another cannabis compound, cannabidiol, to treat seizure disorders, schizophrenia, and other conditions. Cannabidiol is not psychoactive, but unraveling its pharmacology is difficult because it interacts with a variety of receptors beyond the endocannabinoid system.

And some scientists are testing whole plant material. California’s Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research, for example, has studied smoked or vaporized cannabis to treat neuropathic pain, which originates in damaged nerve fibers (J. Pain 2015, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.008). Short-term pain studies indicate that cannabis relieves the pain, “but what we haven’t answered is whether it works forever,” says Igor Grant, director of the center and a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. “Does the efficacy remain, or do people get used to it and it no longer works as well? Is it possible that after a year you see side effects that you don’t see after a few weeks?”

Advertisement

With broadening legalization of medical and recreational marijuana in the U.S., “a lot of people are self-testing for a number of different conditions,” Piomelli says. “We typically hear about positive favorable effects because those tend to surface, but we don’t have studies that are done appropriately for all these different uses.”

Compared with conventional antidepressants, ketamine is “remarkable,” says David Feifel, a professor of psychiatry and director of a center specializing in advanced treatments for depression at the University of California, San Diego.

Starting in 2004, Carlos A. Zarate Jr., chief of the Experimental Therapeutics & Pathophysiology Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health, led a study in which his team used ketamine to treat 17 patients who had already been through an average of six antidepressants. They observed 12 patients (71%) improve within 24 hours.

That speedy response time contrasts with conventional antidepressants such as sertraline and fluoxetine, which target serotonin pathways in the brain and typically take weeks to work.

Ketamine binds to the same glutamate receptors as ibogaine. Its half-life in the body is two to three hours. But ketamine’s relief of depression lasts an average of around seven to 18 days, with some patients improving for as long as five months, Feifel says.

Zarate is conducting a range of studies—including neurological imaging, proteomics, and metabolomics—to unravel ketamine’s effects in the brain. He points to dehydronorketamine as a particularly interesting metabolite. Zarate and colleagues have found that it may play a role in alleviating depression by interacting with a nicotinic receptor involved in long-term memory (Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.023).

A racemic mixture of ketamine enantiomers is currently approved and manufactured for use as an anesthetic. Doctors administer it for depression off-label as an injection or intravenous infusion, at a dose low enough to avoid unconsciousness. Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen R&D unit has an intranasal formulation of the S-(+)-ketamine enantiomer, known as esketamine, in clinical trials. In both cases, patients are dosed in clinics and monitored until the altered consciousness effects dissipate. Allergan is developing a related compound, rapastinel, that targets the same glutamate receptors but does not induce altered consciousness.

None of the compounds provides a single-dose cure for depression—they all require continuing treatment. Nevertheless, they could be a much-needed help for people who have otherwise lost hope. Says Feifel, “Were it not for the ketamine treatments that they receive, it’s highly likely that several of our patients would not be around today.”

“It was unlike anything I’ve seen in psychopharmacology before,” says Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, of his first trial examining the safety of psilocybin in healthy volunteers.

Those volunteers had positive effects that could last for years. “People had increased satisfaction and quality of life,” Griffiths says. “They felt more generous, centered, optimistic, and caring toward other people in their lives.” Patients’ friends, family members, and work colleagues confirmed the differences.

Griffiths has since conducted trials of psilocybin for tobacco addiction, anxiety, and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer.

Like MDMA, psilocybin targets serotonin receptors. Also like MDMA, the effects of psilocybin seem to stem from patients’ experiences when their consciousness is altered. But instead of undergoing psychotherapy during the acute psilocybin experience, researchers encourage patients receiving psilocybin to focus inwardly and have a deeper experience described as mystical or spiritual by doctors such as Griffiths. Processing with a therapist comes later.

“The best treatment outcomes are with those subjects who, during the course of the psilocybin session, had what they described as a profound psychospiritual epiphany,” says Charles Grob, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine and chief of child and adolescent psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011, DOI: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116).

Cigarette smokers given psilocybin report that the drug helps them understand their nicotine craving. That makes them able to quit more successfully when they’re also undergoing a cognitive behavioral therapy program for tobacco addiction, Griffiths says (J. Psychopharmacol. 2014, DOI: 10.1177/0269881114548296).

For people diagnosed with cancer and struggling with the existential fears associated with dying, “it’s harder to say what the nature of the attitude shifts are,” Griffiths says. “But it seems to be an increased sense of wonder and openness to the mystery of life and death. In spite of the tragedy that they’re dying, they might see that there’s something beautiful and organic about the process.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter