Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Ultrasound implant safely opens blood-brain barrier in patients

New method could help anticancer drugs reach brain tumors

by Michael Torrice

June 17, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 25

The cells lining blood vessels in the brain form tight, tough-to-penetrate junctions that prevent toxic molecules from slipping into the brain.

Unfortunately, this blood-brain barrier also blocks cancer drugs from reaching tumor cells in the brain, creating a significant drug-delivery problem.

Now, preliminary results from a Phase I/II clinical trial suggest that a small implant that emits ultrasound waves can safely open the blood-brain barrier in people, potentially allowing drugs in (Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6086).

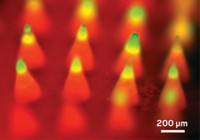

Scientists have previously tested ultrasound methods in animals and found that the techniques can aid drug delivery to the brain. These methods often rely on injecting microbubbles—typically fluorinated gases encapsulated in lipid spheres. The sound waves cause these bubbles to expand and compress. That mechanical energy helps loosen the junctions between endothelial cells lining blood vessels.

To translate such a treatment into people, the company CarThera, founded by Alexandre Carpentier, a neurosurgeon at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, in Paris, developed SonoCloud, an 11.5-mm-diameter ultrasound transducer that surgeons can implant in a hole in patients’ skulls. Carpentier envisions a brain-cancer patient receiving such an implant after a tumor biopsy or a surgery to remove parts of a tumor.

In the new study, the team reported data from 15 glioblastoma patients who had received the implant. Before these patients were treated with the cancer drug carboplatin, they received a 2.5-minute ultrasound session.

By using magnetic resonance imaging to watch a gadolinium contrast agent enter the brain, the researchers found that these sessions opened the blood-brain barrier. And the patients didn’t experience adverse effects from the ultrasound—no signs of hemorrhaging, no complaints of pain, and no indications that speech or motor control was disrupted.

CarThera will start a Phase III trial in 2017 to assess how ultrasound treatments can improve chemotherapy for brain cancer patients. Also, Carpentier is interested in determining if the device can help treat Alzheimer’s disease. Some studies in animals suggest that ultrasound can clear out toxic protein plaques from the brain, in part, by temporarily opening the blood-brain barrier.

Nathan McDannold of Harvard Medical School says the clinical trial data are an impressive milestone for the ultrasound therapy field. He is working on similar methods that don’t rely on an implant and instead use an external array of 1,000 ultrasound transducers to focus on a target in the brain. So, he says, although the SonoCloud is more invasive, it is a simpler system.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter