Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Scientists beefed up the antibiotic arsenal

Researchers synthesized new molecules, turned to nature to find others

by Bethany Halford

December 13, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 49

The battle between infectious bacteria and humans continued to rage in 2016, with the humans possibly coming out ahead as two groups of researchers managed to revitalize our antibacterial armaments—one by making new macrolide compounds, and the other by mining for them in our noses.

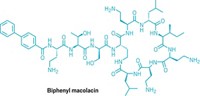

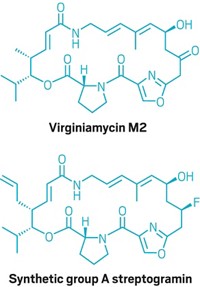

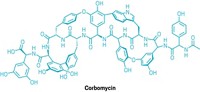

Chemists in Andrew G. Myers’s group at Harvard University figured out how to multiply macrolide munitions with a fully synthetic approach that allows them to make previously inaccessible versions of these compounds characterized by a central ring of typically 14, 15, or 16 atoms (Nature 2016, DOI: 10.1038/nature17967). The Harvard chemists, in collaboration with Macrolide Pharmaceuticals, have used the strategy to make nearly 1,000 fully synthetic macrolides so far. Many of these, Myers tells C&EN, have unprecedented activity against Gram-negative pathogens, including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella that are resistant to several antibiotics currently in use.

Meanwhile, a team led by University of Tübingen microbiologists Andreas Peschel and Bernhard Krismer sifted through the bacteria in our nostrils and discovered a compound that kills Staphylococcus aureus. The molecule, a novel thiazolidine-containing cyclic peptide named lugdunin, is made by another Staphylococcus bacterium, S. lugdunensis, which prevents S. aureus from colonizing about 70% of human noses. Lugdunin represents a new antimicrobial class and is the first to come from a bacterium that lives primarily in people (Nature 2016, DOI: 10.1038/nature18634). The finding could spur scientists to look elsewhere in our bodies for new weapons to fight bacterial invaders.

C&EN's YEAR IN REVIEW

Top Headlines of 2016

- Hawaii explosion cost a researcher an arm

- TSCA reform crossed the finish line

- U.S. elected Trump as president

- The periodic table got four new elements

- Post Dow-DuPont, chemical deal-making waned as 2016 advanced

- Labs made advances in Zika research

- Four ag giants to rule them all

- 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry at a glance

- Brexit bomb exploded

- Focus returned to Iran's chemical industry

- Overtime pay limit doubles under Obama administration

- The CRISPR craze continued

- Perfluorinated compounds got increased scrutiny

- From the lab to the market

- Paris Agreement to curb climate change took off

- World chemical production at a glance

- Flint's water woes lingered

- As China's economy slowed, chemical makers adjusted

- Mostafa A. El-Sayed won the 2016 Priestley Medal

- ACS members on average fared better than young graduates in employment surveys

- ACS invests internationally

- Spun-off firms found their footing in 2016

- Remembering the Nobel laureates we lost in 2016

- ACS proposed chemistry preprint server

- Berkeley College of Chemistry avoided reorganization

- Fight against opioid epidemic continued in 2016

- Noble gas shortages averted, for now

- The shale gas boom by the numbers

- Crop protection products in the crosshairs

- ACS launched new journals

- Website search terms of the year

- Biobased materials hit the big time

- No better deal emerged for Mossville, La.

- U.S. prepares for national food labeling standard

Top Research of 2016

- Mini factory made drugs on demand

- World's first PET-munching microbe discovered

- Liquid metals went to work

- Methylene activation reached new heights

- Biological structures of the year

- Wearable sensors were 'the' fashion accessories of 2016

- Scientists beefed up the antibiotic arsenal

- An enzymatic route to carbon-silicon bonds

- Single-atom catalysts gained a toehold

Revisiting Research of 2006

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter