Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Research on chlorofluorocarbons designated a chemical landmark

Rowland and Molina’s groundbreaking discovery changed the way humans saw their impact on Earth

by Linda Wang

June 12, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 24

With concerns about climate change dominating the news (C&EN, June 5, page 14), it’s fitting that the American Chemical Society awarded one of its most recent National Historic Chemical Landmark designation to the 1974 discovery by F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario J. Molina of the University of California, Irvine, that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) can lead to ozone depletion. Atmospheric ozone helps absorb potentially damaging ultraviolet radiation. Without it, human life cannot survive.

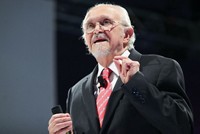

The ceremony and presentation of the plaque took place on April 18 at UCI where, at the time of their discovery, Rowland was a chemistry professor and Molina was his postdoc.

“ACS is deeply committed to communicating the value of science in our everyday lives,” ACS President Allison A. Campbell said in her remarks during the ceremony. “As part of that mission, ACS created the Landmarks program 25 years ago to enhance public appreciation for the contributions of the chemical sciences to modern life and to encourage a sense of pride in its practitioners.”

Until Rowland and Molina’s discovery, CFCs had been widely used as refrigerant gases and as propellants in aerosol sprays. Being chemically inert, they were a welcome alternative to the toxic and flammable compounds previously used in refrigeration and air-conditioning systems, such as ammonia, chloromethane, propane, and sulfur dioxide.

Rowland’s interest in studying CFCs originated with a 1972 talk he attended where the speaker discussed results obtained by British scientist James Lovelock that suggested that practically all the trichlorofluoromethane (CFC-11) ever manufactured was still in the atmosphere. Curious about the fate of CFCs in the atmosphere, Rowland decided to devote part of his research to answering this question.

What Rowland and Molina discovered would change the way humans viewed their impact on Earth. “Chlorofluoromethanes are being added to the environment in steadily increasing amounts. These compounds are chemically inert and may remain in the atmosphere for 40–150 years, and concentrations can be expected to reach 10 to 30 times present levels,” Rowland and Molina wrote in their 1974 paper published in Nature (DOI: 10.1038/249810a0). “Photodissociation of the chlorofluoromethanes in the stratosphere produces significant amounts of chlorine atoms, and leads to the destruction of atmospheric ozone.”

Initially, critics dismissed Rowland and Molina’s hypothesis, arguing that few alternatives existed to using CFCs in refrigerators and air conditioners and it didn’t make sense to take action against a class of highly useful chemicals on the basis of unproven scientific hypotheses.

Over time, however, the evidence in support of Rowland and Molina’s hypothesis grew. For example, in 1985, British scientists who had regularly taken ground-based measurements of total ozone reported in Nature that stratospheric ozone had decreased greatly since the 1960s (DOI: 10.1038/315207a0).

Together with Rowland and Molina’s trailblazing work, the mounting evidence eventually led to the phasing out of CFCs worldwide through the 1987 Montreal protocol, in which 46 countries agreed to cut CFC production and use in half.

In 1995, Rowland, Molina, and Paul J. Crutzen of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, who is another pioneer in stratospheric ozone research, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Rowland died in 2012.

ACS has so far designated more than 80 landmarks, and the program is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year (C&EN, Nov. 21, 2016, page 39). The recognition program celebrates seminal achievements in the history of the chemical sciences and provides a record of their contributions to chemistry and society in the U.S.

To read more about the chemical landmarks program, including previously designated landmarks, visit www.acs.org/landmarks.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter