Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

How plants release their fragrant molecules

Petunias actively pump out volatile odor compounds with the help of protein transporters, study finds

by Michael Torrice

June 29, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 27

Plants synthesize and emit volatile molecules as signals for pollinating insects to come hither, for nearby plants to ready defenses against hungry herbivores, and for many other purposes. Now scientists have discovered that plants actively release these volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with the help of protein transporters in their cell membranes (Science 2017, DOI: 10.1126/science.aan0826).

“It’s pretty huge,” says Jonathan Gershenzon of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, who was not involved in the work. “For years, people thought that plant volatiles just passed through membranes and that there was no active mechanism for getting them out of cells.” This discovery, he says, suggests plants have invested a lot of resources in emitting VOCs, in part to control the timing and rates of their release for certain functions.

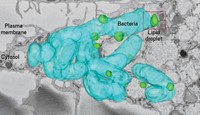

Researchers at Purdue University, led by Natalia Dudareva and including Joshua Widhalm and John Morgan, started to question the diffusion mechanism a few years ago. They calculated that for plants to release VOCs at the rates scientists had observed, cells would have to accumulate high millimolar concentrations of the molecules in their lipid membranes. Such concentrations would be toxic to the cells, Widhalm says.

So in the new study, the team examined gene expression patterns in petunia plants (Petunia hybrida) to find proteins that might actively release VOCs. The researchers looked for genes with high expression levels two days after flower opening—the peak VOC emission time—and low expression levels at the budding stage, when there is little VOC release.

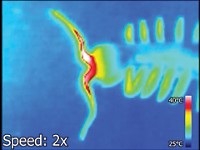

One gene that fits that description is PhABCG1, which encodes for an adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter. When the researchers used RNA interference to lower expression of PhABCG1, the petunias’ VOC emission rates dropped and the volatile molecules started accumulating inside the plants’ cells, indicating that the transporter protein controlled the release of the compounds.

Gershenzon says the work raises many new questions about VOC transport, including how cells move VOCs from where they are synthesized to transporters and how the compounds get through the hydrophilic cell wall.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter