Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Polyladderenes unzip to form semiconducting polymers

Molecules could report mechanical stress in materials

by Bethany Halford

August 4, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 32

Using mechanical force, rather than light or heat, to transform molecules from one form to another has gained traction in the past decade, creating the field of polymer mechanochemistry. Stanford University chemists have made a polymer that transforms from a nonconducting form to a semiconducting one in response to mechanical force. One day, such a material could find use in mimicking the sense of touch or hearing, in which a mechanical force is converted into an electrical signal.

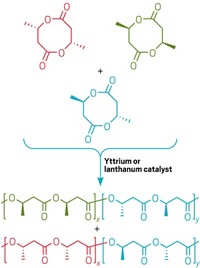

Yan Xia’s group spent two years trying to design the polymer without success. One day Xia was chatting with his Stanford colleague Noah Z. Burns, when Burns showed him the ladderane lipids his group had been synthesizing. The two realized these ladder-like fused cyclobutanes would be a great motif for the polymer Xia envisioned. When subjected to mechanical force, they imagined that the σ bonds in the cyclobutanes would unzip to form continuous π bonds as in polyacetylene (shown). Their colleague Todd J. Martinez joined the collaboration to study the mechanism of this transformation via computer modeling.

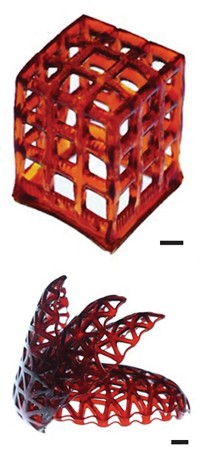

When sonicated in solution—a common technique for applying mechanical force—the polyladderene structure they made goes from colorless to blue in a matter of seconds. With longer sonication, the material darkens and transforms into an insoluble mesh of semiconducting nanowires (Science 2017, DOI: 10.1126/science.aan2797). The polymer could be used, for example, to report on physical stresses in a material.

“It’s a creative work of mechanochemical beauty,” comments Jeffrey S. Moore, a mechanochemistry pioneer at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. “I wish we’d have thought of this ourselves.”

Next, the chemists hope to create simpler structures that accomplish the same task. The polyladderene synthesis currently yields decent amounts, Burns says. “But if we ever wanted to do commercial applications, our synthesis, as it stands, would not be viable,” he says. “So we are actively making simpler monomers that take less steps to get to.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter