Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

A mother’s immune system could influence sons’ sexual orientation

Antibodies produced from carrying multiple male fetuses could help explain why having older brothers increases a man’s likelihood of being gay

by Michael Torrice

December 13, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 49

The greater number of older brothers a man has, the more likely he will be homosexual. Researchers have observed this so-called fraternal birth order effect across societies and over time. Now scientists report a possible biological mechanism behind it.

They found that mothers of gay men with older brothers have elevated levels of antibodies against a male-specific brain protein (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1705895114). The findings support the hypothesis that a mother’s immune response could shape brain structures in male fetuses that are involved in the development of sexual orientation, the researchers say.

The fraternal birth order effect is one of the most robust correlations uncovered in sexual orientation research, and this study is an important first step in understanding the biology underlying the effect, says Qazi Rahman of King’s College London, who was not involved in the work.

Anthony F. Bogaert of Brock University and Ray Blanchard of the University of Toronto first observed the phenomenon in a Canadian population in 1996. Since then, researchers have replicated the findings in societies across the globe. The two psychologists even went back through data collected in the 1940s and 1950s by Alfred Kinsey of Indiana University, who conducted some of the first research on human sexuality, and observed that the effect existed then.

Despite its ubiquity, the effect is modest, Bogaert points out. About 2-3% of men without older brothers are gay. Having four or more older brothers increases that rate to about 6%. So the vast majority of men with multiple older brothers are heterosexual.

About 10 years ago, Bogaert reported data pointing to a biological origin for the phenomenon, instead of a social one. The findings showed that growing up with older step or adopted brothers doesn’t increase a man’s likelihood of being gay, but having older biological brothers who grew up elsewhere does. “It really suggested that there was a before-birth effect and that childhood or adolescence was not playing a role,” Bogaert says.

He and Blanchard had a hypothesis about the biology underpinning the phenomenon. They thought that mothers’ immune systems might treat a specific protein in male fetuses like a foreign invader and this response would grow stronger with each boy born to the same mother. Eventually, the immune response would influence the developing brain of a son born later among a line of male siblings.

To test the hypothesis, the psychologists teamed up with some immunologists and collected blood samples from 54 mothers of gay sons, 72 mothers of straight sons, 16 women with no sons, and 12 men. They were looking for antibodies that target male-specific proteins.

One of the ways our immune systems remember foreign proteins is through antibodies circulating in our blood, says Brock University’s Adam J. MacNeil, who was one of the team’s immunologists. Detecting these antibodies basically gives us a glimpse of what the immune system bumped into in the past, he adds.

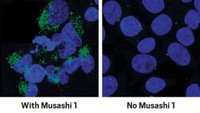

The team was interested in two proteins encoded on the Y chromosome—protocadherin 11 Y-linked and neuroligin 4 Y-linked. Both proteins are expressed in the fetal male brain and both have parts that stick out of cells, making them possible targets of a mother’s immune system.

The researchers found that mothers of homosexual sons had higher levels of antibodies for the neuroligin protein than did mothers of heterosexual sons, and mothers of gay sons with older brothers had even higher levels. There was no trend for antibodies targeting the protocadherin protein.

Not a lot is known about the function of the neuroligin protein except that it helps form connections between brain cells and facilitates communication between them, MacNeil says.

Because the study’s sample size was small and the observed effect was modest, Rahman thinks the experiment should be replicated on a larger scale to confirm the results. Bogaert also hopes other groups will try to replicate it: “One study just won’t cut it,” he says.

Also Bogaert says it’s important not to think of this mechanism as a disorder—as something pathological caused by a mother’s immune response. “An atypical biological process creating a trait doesn’t mean that the trait it produces necessarily needs fixing,” he adds.

In general, he says, work on uncovering the biological basis for sexual orientation has helped the gay rights movement. “It suggests that sexual orientation is not a choice,” Bogaert says. “It also resonates with gay people’s lived experience—that they have felt different from early on in their lives.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter