Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

ACS News

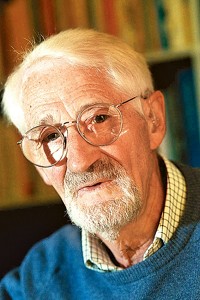

Nobel Laureates Paul D. Boyer and Jens C. Skou die at 99

Biochemists were two of three who shared 1997 prize for work related to adenosine triphosphate

by Stu Borman

June 12, 2018

Two laureates who shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Jens C. Skou and Paul D. Boyer, died less than one week apart, on May 28 and June 2, respectively. Both men were 99.

Skou discovered the first molecular pump, the ion-transporting enzyme Na+,K+ adenosine triphosphatase. And Boyer determined the mechanism of action of the enzyme adenosine triphosphate synthase. Both discoveries involved adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal energy currency of cells.

Skou was born in 1918 in Lemvig, Denmark, to a wealthy family of timber and coal merchants. After graduating from high school in 1937, he studied medicine on the advice of a colleague. He earned his M.D. at the University of Copenhagen in 1944, while Germany was still occupying Denmark during World War II. After an internship, he joined Aarhus University in 1947 to study the mechanism of action of local anesthetics. He married Ellen M. Nielsen in 1948 and earned a Ph.D. in physiology at Aarhus University in 1954.

Skou remained at Aarhus for the rest of his career. In 1957, while continuing to study the mechanisms of anesthetic drugs, he discovered Na+,K+ adenosine triphosphatase in crab nerve cell membranes. The enzyme helps maintain proper salt balance across neuronal cell membranes, setting up voltage differences that cause nerve impulses and muscle contractions.

From then on, “my scientific interest shifted from the effect of local anesthetics to active transport of cations,” Skou wrote in his Nobel biography. He retired in 1988 and later shared half of the 1997 Nobel Prize for his 1957 discovery.

During his career, Skou was a strong advocate of non-targeted funding, support for basic research that scientists receive routinely, without having to file laborious applications. “His tireless struggle to tell politicians and the outside world about the importance of non-targeted funding for research has had a huge impact on the research environment,” said Lars Bo-Nielsen, dean of health at Aarhus University. “He has been a cornerstone and a beacon for research.”

Skou is survived by his wife Ellen, their two daughters and sons-in-law, four grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

Boyer, who shared the 1997 chemistry prize for determining the mechanism of action of ATP synthase, died a few days after Skou. Boyer “had outstanding character,” says David Eisenberg, who Boyer recruited to the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1968. “Everyone liked him and admired him. He was a modest and thoughtful leader.”

Boyer was born in 1918 in Provo, Utah. “You have proven yourself a most outstanding student,” Provo High School chemistry teacher Rees Bench wrote in Boyer’s yearbook, foreshadowing the Nobel Committee’s judgment. Boyer earned a B.S. degree in chemistry from Brigham Young University in 1939 and married Lyda Whicker that same year.

After earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin in 1943, Boyer participated in a war-related research project at Stanford University to stabilize serum albumin for battlefield treatment of shock. He then returned to the University of Wisconsin and built a home nearby largely by himself, serving as contractor, plumber, electrician, and carpenter.

Advertisement

Boyer was chair of the Biochemistry Section of the American Chemical Society from 1959 to 1960. In 1963, he moved to UCLA, where he remained for the rest of his career. He was founding director of UCLA’s Molecular Biology Institute, to which he recruited Eisenberg and others. He managed the construction of the institute’s building, which was later named in his honor. And from 1969 to 1970, he served as president of the American Society of Biological Chemists, forerunner of the American Society for Biochemistry & Molecular Biology.

In the 1970s, Boyer developed a set of mechanistic proposals that described how the enzyme ATP synthase converts adenosine diphosphate and inorganic phosphate into ATP. For this work, Boyer shared the other half of the 1997 Nobel Prize with the researcher who experimentally verified his ATP synthase mechanism, John E. Walker of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Boyer donated a majority of his prize money to fund chemistry postdoctoral fellows at UCLA and two other institutions.

Eisenberg recounts that after securing key funding for the Molecular Biology Institute building, in 1973, Lyda and institute faculty members brought music, champagne, flowers, and a 20-foot sign to the airplane door at Los Angeles International Airport to celebrate Boyer’s return from Washington, D.C. But Boyer didn’t disembark and instead showed up behind the group. He had taken an earlier flight. “It was typical of Paul to be in a hurry,” Eisenberg says.

Boyer is survived by his wife Lyda, two daughters, eight grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren. A son, Douglas, died in 2001.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter