Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Art & Artifacts

Video: This chemist is helping save ancient history with X-ray tools

Researchers at Shumla are fighting against time and the elements to document some of North America’s oldest rock paintings in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

by Manny Morone

July 10, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 28

Because of dams built on the Rio Grande and an increase in flash floods in Southwest Texas, the nonprofit Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center has embarked on a quest to document more than 350 ancient rock paintings near the Lower Pecos Canyonlands before they’re irreparably damaged. Among Shumla’s archaeologists is a chemist, Karen Steelman, who is incorporating new X-ray fluorescence techniques to help rediscover the painting techniques of the people who once lived there. In the latest episode of Speaking of Chemistry, we talk to Steelman about one of the stories that Shumla’s team thinks it has uncovered peering beneath the surface of the rock paintings—among the oldest known in North America.

Subscribe to C&EN’s YouTube channel for more Speaking of Chemistry and news videos.

The following is the script for the video.

Manny: In the small town of Comstock, Texas—near the US-Mexico border—there’s a team of archaeologists fighting against time to study these, some of the oldest rock paintings in North America made by the native people who lived there between 1,500 to 4,000 years ago.

Karen Steelman: In the last, say, 60 years, we’ve seen elevated levels of deterioration at the sites. And whether that’s due to climate change or raised humidity levels, we’re not exactly sure. But we do know that we are starting to lose these panels.

Manny: That’s Karen Steelman, the science director at Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center, a nonprofit that researches the paintings of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

She’s a chemist working among those archaeologists studying more than 300 sites.

And using high-resolution photography and X-ray technology, Steelman and her team are trying to uncover and record history that could soon be lost.

Heavy rains and dams built on the Rio Grande can drive water levels high enough to touch rock paintings and wash away the history that’s been sitting there for thousands of years. And lately, flooding is becoming more common.

That’s why in 2017, Shumla embarked on the Alexandria Project to get baseline documentation on these panels by making panoramic photos and 3-D models of the paintings and getting what data they can about how the panels were painted. It had to be fast, and it had to keep the paintings in as good condition as possible.

So why does Shumla need a chemist like Karen Steelman to do that? Well, beyond the radiocarbon dating and spectroscopy that she does in the lab, she’s hiking out to the painting sites with the archaeologists to help them using portable analytical equipment.

One obstacle archaeologists have is that there’s a thin layer of minerals that’s built up over time on the paintings. That makes the colors and figures harder to see with the naked eye.

For a more thorough inspection, archaeologists like Shumla’s founder, Carolyn Boyd, have often used digital microscopes to look at chunks of these walls that fall off over time, and they can see layers of paint—sometimes several on top of each other—under that mineral buildup.

But they don’t want to hack off a piece of the wall every time they want to see how exactly the paint’s layered. After all, they’re trying to preserve the paintings, not destroy them. So that’s where Steelman comes in.

Karen Steelman: A lot of the people will say the paintings look faded, but it’s just really that they’re obscured by maybe a 50–100 micron accretion of mineral growth. And when we’re using the X-ray fluorescence technology, we’re able to penetrate that and see those underneath layers.

Manny: She and the researchers at Shumla saw an opportunity in X-ray tech and came up with the method of documenting paint layers that they use now, which takes advantage of new portable X-ray fluorescence instruments, or pXRF instruments for short. You can just hold them up to the wall and get an idea of what’s under the surface.

The way XRF works is basically “Let’s shoot X-rays at something and see what comes out.” It starts with the X-ray radiation knocking low-energy electrons off of atoms in the paintings. With those electron holes left behind, higher-energy electrons swoop in and fill the gaps, emitting photons in the process. These photons have specific energies that correspond to the atom that spit them out. So by measuring all the photons’ energies, you can figure out what elements are in your sample.

So that’s what the pXRF instrument’s readout tells you after just a minute of holding the detector up to the painting, no wall chipping required.

Knowing what elements are present behind the layers of paint and buildup has helped support a theory that Shumla archaeologists had about paint layering.

In several of these murals, the entire black portion had been painted first, before any other color was put down. Then the red portion, then yellow, then white.

That layering order might seem like just a small fun fact, but archaeologists found the pattern held across several other sites in the region. And they think it means something big. Like that each of these panels was made deliberately as a meticulously planned work that tells a cohesive story.

Some archaeologists, like Carolyn Tate of Texas Tech, are drawing on Shumla’s work to see if these images represent something more like a written language.

Carolyn Tate: So it holds this whole discovery of the layers of paint, which led to the compositions, which led to the conventionalized symbols, which leads into the development of graphic communication systems and writing, that’s just huge in terms of the cultural history of the Americas.

Manny: The hope is that the paint-layering data can tell researchers more about what the paintings meant to the people that made them.

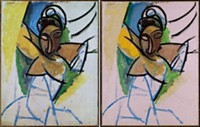

So in the White Shaman Mural, which stands near the US-Mexico border, Shumla looked at this spotted deer painting with a digital microscope. It looked like it had 11 black dots under its red outline.

But look here. Is that black region nestled under the red paint a 12th spot, a dark bit of rock, or something else? Shumla researchers couldn’t tell even with digital microscopes.

But using pXRF instruments, Shumla confirmed the presence of manganese, which is found in black pigment, and that it was—in fact—a 12th black spot.

Karen Steelman: As a chemist, you know, I’m like, 11 dots, 12 dots, does it matter? But it does because these were intentionally painted and intentionally put on the wall. It wasn’t just randomly put up there.

Manny: Specifically, archaeologists at Shumla think the number 12 could link the deer to a Mesoamerican deity called the Lord of the Dawn, and it would follow that the people who made these paintings could’ve shared a core belief system with the people who eventually became the Aztecs and the Huichol.

That potential link was brought to light with XRF data after the rock painting sat there for thousands of years.

So Shumla is still chipping away—figuratively—at this cultural history. And Karen tells us that with changes to landscape, the climate, and border policy threatening the paintings, the time to document these sites is now, before the region’s stories are lost forever.

She also told us that they’re always looking for interns. So if you’re interested in carrying a backpack full of cameras and X-ray equipment and hiking out to sites in the southwest, we’ve got more info on Shumla in the description.

Huge thanks to Karen Steelman for helping out with this video. And to Carolyn Boyd, Shumla’s founder, who’s been studying these paintings—and people—since before pXRF data even existed for them. And thanks to you for watching. If you liked this video, then please subscribe. If you didn’t like this video, then also click subscribe. Why not?.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter