Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Cost Control Reigns

European producers focus on economies of scale and on more sophisticated products

by Patricia L. Short

March 15, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 11

COVER STORY

COST CONTROL REIGNS

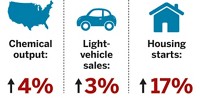

Coming off what most executives considered a challenging year, the European petrochemical industry is looking forward to a better couple of years ahead.

Indeed, the final months of 2003 held a first glimmer of improvement. For Danish petrochemical maker Borealis, for example, the year as a whole was difficult, but the fourth quarter was positively impacted by stronger demand, lower costs, and higher margins. "It was encouraging to end on such a robust note," Chief Executive John Taylor says.

European producers see predictions of continuing growth for the coming year--a welcome sign for an industry that is in the throes of reshaping itself to maintain its presence in the global marketplace.

As Andrea V. Borruso, senior consultant at the Zurich offices of SRI Consulting, observes, the European industry is suffering because of modest market growth. "This is not because there is a lull in economic growth, but because, relatively speaking, it is a mature market," he says. Regardless of what the overall economy is doing, the growth of the petrochemical industry will be lower in Europe than it will be in developing countries.

What that means, adds Koos van Haasteren, managing director for polyolefins at SABIC EuroPetrochemicals, is that the industry in Europe is having to change the way it looks at life.

"We have three very difficult years behind us," van Haasteren says. Roots of those difficulties lie in the 1990s, he suggests, when "the industry was doing particularly well and capacity was overbuilt. But after the euphoria in the mid- to late-1990s, there was an oversupply, with reduced demand, caused by an adverse economic climate."

Now, he adds, the industry is going into a new era, marked by "a huge drive for scale and a focus on internal processes. Companies are becoming bigger, with acquisitions and mergers going on. I'm coming from DSM--we were part of that," he says, referring to SABIC's 2002 purchase of DSM's petrochemicals business.

Moreover, companies have become more bottom-line oriented, van Haasteren says. "There is an increasing focus on core competencies, key application segments, and markets for the players in this field."

Bill Colquhoun, vice president for lower olefins at Shell Chemicals, agrees that, for European petrochemicals, "what we see is primarily consolidation and efficiency. Certainly, there will be growth, but it will be satisfied by debottlenecking investments and imports from the Middle East."

According to van Haasteren, one of the challenges facing the industry is to reduce the cyclicality of polyolefin prices. "Our industry is increasingly cyclical, with volatile prices. A lot is driven by sentiment in the European market, causing large fluctuations in demand."

PRODUCERS, he adds, will have to better understand buying patterns and fluctuations--and also cooperate well with customers--to create a more regular demand. "We want to reduce the effects of speculative buying so customers concentrate less on reducing the cycle and more on producing good products for their own customers," he says.

Over the medium term, van Haasteren predicts, there will be capacity expansions in Europe, but not many. Expansions "will go hand-in-hand with players closing old capacity. There is a lot of old, less competitive capacity in the industry, especially in polyethylene. Polypropylene is a lot younger industry, so there is less old production capacity to go. But we have seen some initial moves in this, and I anticipate more will follow," he says.

A case in point is Borealis, which has begun building a new polyethylene plant in Austria to feature its Borstar technology, to meet what the company sees as rapidly growing demand for high-performance linear low-density polyethylene. The plant will replace three old polyethylene lines when it opens toward the end of 2005.

However, SRI's Borruso maintains that the historical European industry structure of many smaller plants is, ironically, a potential strength.

"We have in Europe a certain asset--the petrochemical asset structure," he explains. "You cannot just wipe it out simply because the market is growing slowly. But this is survival of the fittest, which are the most integrated plants. Nonintegrated, smaller, and older plants will disappear--or they could convert to highly sophisticated specialty products."

A large, commodity-oriented plant, he adds, is limited in what it can produce: Economies of scale keep it churning out a limited number of product grades. On the other hand, if a producer has several small polymerization lines, these could be converted to very specialized product runs, while maintaining a cost-competitive position.

"My theory," Borruso says, "is that we should start defining a threshold growth of the market. Below a certain value, there is a declining market and obsolescence. Above a certain value, that sector can survive. For example, polyvinyl chloride and low-density polyethylene in Europe now are below that threshold. Polypropylene and linear low-density polyethylene are above. Polystyrene is in between, as is acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene.

"If you have a market with no growth, you cannot justify new investment," he adds. "If you want to scrap and build, because of economies of scale, you are going to have to scrap a lot. Some producers don't have that much excess--they can only revamp. But if producers are just revamping, they cannot justify improvements leading to economies of scale. And that dilemma leads to obsolescence."

Therefore, he concludes, "high-growth products will remain competitive, and low-growth products will suffer more. If you look at the European market, there is a high sophistication of products, a high level of technology, and a high per-capita purchasing power. The combination of these factors will sustain a certain kind of market."

For commodities, however, control of costs remains crucial. According to Jeroen van der Veer, the recently named chairman of Royal Dutch/Shell, Shell Chemicals' philosophy is to ensure that all its plants match or better the lowest production costs of its competitors.

When the company makes a capital investment, van der Veer adds, "part of the investment is to ensure our machines stay competitive." However, he sees the day approaching when Europe will no longer be exporting petrochemicals. "It won't be too long before all areas are importing, with only the Middle East exporting," he predicts. "The feedstock cost advantages [of projects in the Middle East] more than compensate for any logistical costs."

Feedstock costs are, of course, important--but perhaps not as much as once thought, suggests van der Veer's colleague Colquhoun. Take oil, for example. According to Colquhoun, Shell has worked on a number of scenarios in which one of the parameters is the cost of oil.

Historically, the firm has worked with a scenario of $18 per barrel. With that assumption, he says, leading Western European crackers will be competitive, to the extent that there is an economic disadvantage for Middle Eastern producers to export into Europe. Middle Eastern producers, however, do have an economic incentive to export into Asia, he says.

If oil increases to $25 per barrel, the trade impact on Europe doesn't change that much, he says, because while there now would be an advantage to exporting to Europe, the profit in exporting into Asia would be even greater.

Colquhoun's conclusion: Shell's scenario on the impact of imports into Europe doesn't really change despite higher oil prices.

"If a company has a leading cracker in Europe, it has a reasonable life ahead," he concludes. "There may be some closures, but lots of reasons why there may not. A producer must continually look at ways to contain costs, looking at scale and feedstock flexibility." And producers must continually improve logistics--"It is the delivered cost we are competing on."

There will be a continuing role for smaller producers on a regional basis, Colquhoun believes, but "they must work out their own strategies. They can't ignore costs."

As Jacques Autin, European Chemical Industry Council executive director and head of the Association of Petrochemicals Producers in Europe, puts it, the cost, research, and regulatory issues that affect the overall chemical industry are magnified for the petrochemical segment. However, he sees one strong underlying support: the fact that the industry is, in essence, a by-product industry.

"PETROCHEMICALS are a consequence of the oil-refining industry in Europe," he points out. "We represent a very small proportion of the output--only 7 to 9% of total refinery output in Europe. Because Europe is not an oil producer, we are dependent on the processes using oil. The main users are energy, transportation with gasoline, and heating, so we still have a good story. We start with naphtha, from refining."

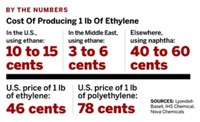

Until recently, naphtha has been a higher cost starting material than the ethane used in the U.S. and the Middle East. However, in the U.S. in particular, liberalization of energy prices has skewed the price of natural gas and consequently of feedstock ethane.

As Shell's Colquhoun sees it, what characterizes the U.S. has been its historical advantage over ethane. "The U.S. was the supplier of choice into Asia for many years," he points out. "But that advantage has been reduced, as prices have gone up for ethane. Prices are more in line with ethane's calorific value compared with oil. It is not uncompetitive, but the export capacity of the U.S. has been reduced by about 75% already." The upshot: "The U.S. won't be an export player of any importance in the future. That's quite a switcharound."

There is no room for complacency, of course, but as Autin puts it: "The whole of the basic petrochemical industry in Europe cannot be replaced at once by imports. Europe can't let it die off. If we do our homework--and if we have an integrated pipeline network through Europe--we can restructure our industry and strengthen it. We can continue to develop our chemicals."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter