Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

No Change in Numbers of Women Faculty

C&EN's annual survey shows that women remain underrepresented in top chemistry departments

by CORINNE A. MARASCO, C&EN WASHINGTON

September 27, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 39

There has been little change in the percentage of women faculty members in the top 50 chemistry departments in the five years that C&EN has examined this topic, and what little progress there is continues to be unevenly distributed. Women are still underrepresented among the full professor ranks, despite slow and steady headway overall.

C&EN surveyed schools identified by the National Science Foundation as having spent the most on chemical research in 2002, the latest year for which data are available. The schools were contacted by e-mail and telephone and were asked to provide the number of male and female tenured and tenure-track faculty holding full, associate, and assistant professorships with at least 50% of their salaries paid by the chemistry department for the 2004–05 academic year. These numbers exclude emeritus professors, instructors, and lecturers. The response rate was 100%.

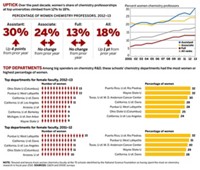

In academic year 2004– 05, women represent 12% of the total chemistry faculty at the top 50 institutions. This is the same percentage as in 2003–04 (C&EN, Oct. 27, 2003, page 58) and 2002–03 (C&EN, Sept. 23, 2002, page 110) but up from 11% in 2001–02 (C&EN, Oct. 1, 2001, page 98). In absolute terms, the total number of faculty positions increased from 1,592 last year to 1,594.5, and the total number of positions filled by women increased from 196.5 to 197.

A COMPARISON of this year's list to last year's shows some differences in the schools included. Schools added to the list in 2004 are the State University of New York, Buffalo; SUNY Stony Brook; the University of Virginia; and Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University. Both Virginia schools were on the list in 2002 but not in 2003. Schools that were on the list in 2003 but dropped off in 2004 are Columbia University, the University of Chicago, the University of Georgia, and the University of Southern California. Together, those schools had nine female chemistry faculty members, whereas the four schools that replaced them have 12.

Among the schools with the highest proportion of women in the total faculty, Rutgers University maintains its first-place spot: 10 women, or 25% of the faculty. The University of California, Los Angeles, is next with nine women, or 23% of the faculty. Purdue University follows with 10 women who make up 21% of the faculty. This year, there is a three-way tie for fourth place between Florida State University, SUNY Stony Brook, and the University of Colorado, where women make up 19% of the faculty. Tied for fifth place are Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Arizona, which both have six women who make up 18% of the faculty.

At the other end, three schools on the list this year--Emory University, the University of Georgia, and the University of Virginia--have just one woman on their faculty. Eleven schools have two women, and 10 have three.

Women continue to be concentrated in the assistant and associate professor ranks. Women make up 20% of assistant professors, which is down one percentage point from last year but still higher than the 18% share in 2000, the first year of the survey. Women's representation among associate professors has hovered around 20% since the beginning of the survey; this year, it's at 19%. By comparison, women currently account for 8% of full professors, the same as last year. The 2000 baseline was a 6% share of full professorships.

These numbers are consistent with a 2004 report from NSF, "Gender Differences in the Careers of Academic Scientists & Engineers." The report uses data from the NSF biennial Survey of Doctorate Recipients to examine gender differences for four outcomes that reflect successful progress in an academic career: tenure-track placements, achieving tenure, promotion to associate professor, and promotion to full professor.

NSF finds evidence to suggest that among academic scientists and engineers, women are less successful in their academic career paths than men. Some of the disparity may be related to family characteristics: Married women and women with children tend to be less successful by those measures than men who are married and have children. NSF determined that the estimates of success rates were insensitive to either primary work activity or the characteristics of academic employers.

IN ANALYZING tenure-track positions, NSF found that women with eight or nine years of postdoctoral experience who are employed full time in academia are less likely than men to be tenured.

NSF's analysis suggests that women's chances for earning tenure are influenced by family characteristics: Opting to have children later--rather than earlier--in their careers is positively related to women's chances for earning tenure.

Women with 14 or 15 years of experience since earning their Ph.D.s who work full time in academia are more likely than men to be found in the junior ranks and less likely to be full professors. Furthermore, women are less likely than men to be promoted to senior ranks.

Although the NSF research focuses on a limited number of outcomes, there are other questions worthy of exploration when considering this topic. For example, do women face greater mobility constraints than men when selecting jobs, especially when they must find new employment after failing to receive tenure? What gender differences exist between full-time and part-time employment?

The assumption that women science and engineering faculty lag behind their male counterparts in achieving academic career milestones is reinforced by five years' worth of data collected by C&EN, combined with the NSF analysis. That women's share of full professors and total faculty increased just two percentage points in both cases over five years suggests that there are gender-related factors impeding their progress, compared with that of their male counterparts.

MORE ON THIS STORY

Women In Academia

Table 1 - Women In Academia Only 8% of full chemistry professors at top 50 universities are women

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter