Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Depression

by Sophie L. Rovner

February 9, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 6

“I never really tried to commit suicide, but I came awfully close because I used to play matador with buses," said Paul Gottlieb, a publisher in the art world who suffered from depression. "I would walk out into the traffic of New York City with no reference to traffic lights, red or green, almost hoping that I would get knocked down."

Living with depression, Gottlieb said, feels "as if your inner core is being squeezed in such a way that it hurts. You feel as if your tissue has been wounded."

Rodolfo Palma-Lulión, who recently graduated from college, recalled his own battle with the disorder: "I didn't feel any emotions. My real feeling was just pure numbness. It was almost like I was under water with my eyes and my ears all shut off, and I was just there."

Rene Ruballo, a retired police officer, said: "It started with my loss of interest in basically everything that I like doing. I just felt like giving up sometimes. Sometimes I didn't even want to get out of bed. I am thinking there's got to be something wrong because I'm waking up and I feel like nothing matters. My children, my family ... nothing matters."

These are the experiences of men who have wrestled with depression. Their comments are featured in an educational campaign sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Through its "Real Men. Real Depression" campaign, NIMH hopes to encourage men--who are less likely than women to recognize that they are depressed or to seek help for the condition--to get the assistance they need.

More than 12 million women and 6 million men in the U.S. are affected by depressive illnesses in any given year, NIMH estimates. Another 2.5 million have bipolar disorder (BPD). The tragedy is that fewer than half of people with depression seek treatment. With appropriate treatment, however, more than 80% of people with depressive disorders improve.

Symptoms of depression include a persistent sad, anxious, or "empty" mood; hopelessness, pessimism, guilt, worthlessness, and helplessness; social withdrawal and loss of interest in hobbies and activities that were once enjoyed; decreased energy; difficulty concentrating and making decisions; sleeping difficulties; physical symptoms, such as headaches, digestive disorders, and chronic pain, that don't respond to routine treatment; and thoughts or attempts of suicide, according to NIMH.

DEPRESSION CAN INCLUDE any of these symptoms to varying degrees of severity. It can last for just a couple of weeks or drag on for months, even years. The symptoms of clinical depression--also referred to as major depressive disorder (MDD) or unipolar depression--are severe enough to interfere with daily functioning and with relationships. It may occur just once or recur periodically throughout a lifetime. Dysthymia, or dysthymic disorder, is a chronic but less serious form of depression.

Another form of depression is seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which strikes during winter and afflicts approximately 6% of Americans, according to the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD). The condition may be linked to melatonin, a sleep-related hormone secreted by the pineal gland. "This hormone, which may cause symptoms of depression, is produced at increased levels in the dark," according to the website for the National Mental Health Association (NMHA). The long nights of winter therefore boost melatonin production. Therapy with bright lights or sunlight reduces melatonin secretion and can ameliorate SAD symptoms. Antidepressants can also work.

Postpartum depression (PPD) engulfs 10 to 20% of new mothers. PPD resembles clinical depression but "may include specific fears such as excessive preoccupation with the child's health or intrusive thoughts of harming the baby," NMHA notes.

Possible causes of PPD include hormonal fluctuations (including a drop in levels of estrogen and progesterone) and the stress associated with childbirth and any other concurrent events. Thyroid levels can plunge after giving birth, causing depression-like symptoms that can be corrected with thyroid medication.

Unlike unipolar depression, bipolar disorder affects men and women equally. And it tends to run in families. Also known as manic depression, this severe mental illness generally begins in late adolescence. BPD combines episodes of depression with mania, an elevated mood in which a person is highly energetic and prone to risk taking, poor judgment, and grandiose delusions. A patient in the grip of mania needs less sleep and tends to be irritable. If untreated, mania can develop into psychosis. As many as 20% of those with BPD who aren't treated take their lives, according to NIMH.

Depression often occurs with other psychological disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder, according to NIMH's "Men & Depression" booklet.

People with other serious illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes are more prone to depression than is the general population, reports NMHA. Depression may, in fact, exacerbate the harm caused by these other conditions. Among patients who have had coronary artery bypass surgery, those who suffer from moderate to severe depression or persistent depression are more likely to die after the surgery [Lancet, 362, 604 (2003)].

Alcoholics are nearly twice as likely to suffer from major depression, and more than half of people with BPD have a substance-abuse problem. Depressed people smoke cigarettes more than others and have a harder time quitting. The habit may represent a subconscious effort to self-medicate with nicotine--a hypothesis supported by research conducted by Howard University associate pharmacology professor Yousef Tizabi and colleagues. They studied rats that serve as a model for depression and found that the rats' symptoms improve when they are given nicotine. When the rats are given mecamylamine, a nicotinic receptor antagonist, the beneficial effect of nicotine is blocked. The researchers believe that nicotinic receptor agonists could prove useful in treating depression.

Traumatic brain injury is also associated with an increased likelihood of major depression [Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 61, 42 (2004)].

And depression can arise as a side effect of medications for other conditions. As these examples show, the term "depression" encompasses several different conditions with a range of causes. What unites them is an interaction between genetics and environmental factors such as stress and substance abuse.

Although researchers don't entirely understand the mechanics of depression, they have amassed tantalizing clues to explain the disorder.

THEY KNOW THAT depression interferes with the balance of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine--though this is only part of the story. They have determined that the medications used to treat depression "work by increasing the availability of neurotransmitters or by changing the sensitivity of the receptors for these chemical messengers," as the mental health support and advocacy organization known as NAMI explains on its website.

But what upsets neurotransmitter balance in the first place? One theory is that depression shrinks particular regions of the brain. For instance, the hippocampus is smaller in patients who suffer from recurrent major depression than in comparison subjects. The hippocampus plays a role in learning and memory and is part of the limbic system, which is involved in emotion and motivation.

Furthermore, the hippocampus tends to be smallest in those patients who go without treatment for their depression for the longest period of time, according to Yvette I. Sheline, an associate professor of psychiatry, radiology, and neurology at Washington University in St. Louis, and colleagues [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 1516 (2003)]. "The key implication of this study," writes Sheline's team, "is that antidepressants may protect against hippocampal volume loss associated with cumulative episodes of depression."

Findings by other researchers support this idea. Although serotonin and norepinephrine levels rise rapidly after a patient begins taking an antidepressant, "the onset of an appreciable clinical effect usually takes at least three to four weeks," note René Hen, an associate pharmacology professor at Columbia University, and colleagues in a Science paper [301, 805 (2003)]. The Hen team set out to provide evidence that the lag represents the time needed to grow new neurons in the hippocampus and that the growth is necessary for the antidepressants to work.

The researchers determined that mice in which hippocampal neurogenesis is prevented by X-ray damage do not respond to tricyclic or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants. They also studied mice lacking the gene to make the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor. When such mice--which are more anxious than normal mice--are treated with an SSRI antidepressant, their behavior doesn't improve, nor do they undergo neurogenesis. However, these mice show both behavioral improvements and neurogenesis in response to tricyclic antidepressants, which affect the neurotransmitter norepinephrine rather than serotonin.

One possible cause of the hippocampal damage seen in depressed people is stress. Stress apparently interacts with depression to shrink existing neural cells and limit growth of new ones, explains Ronald S. Duman, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology and director of the molecular psychiatry division at Yale University's School of Medicine. Stress and depression exert this control in part through a cellular signaling cascade involving cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and the associated cAMP response-element binding protein (CREB).

Duman has found evidence that antidepressants counteract the deleterious effects of stress and depression by boosting activity in the cAMP pathway, which in turn upregulates, or cranks up, the pathway for the gene transcription factor CREB. This increases expression of neurotrophic factors that enhance survival of neural cells. Antidepressants also appear to increase production of new neural cells through the cAMP-CREB pathway.

An individual's physiological and psychological vulnerability to stress may depend in part on genetic makeup. For instance, University of Pittsburgh psychiatry professor George S. Zubenko has found that variations in the gene for CREB are linked to susceptibility to depressive disorders in women--possibly offering one reason that more women than men experience depression [Mol. Psychiatry, 8, 611 (2003)]. Zubenko has identified several other chromosomal regions that may influence susceptibility to depressive disorders [Am. J. Med. Genet., 123B, 1 (2003)].

In response to stressful life events, individuals carrying the short version of an allele in the promoter region of the gene for the serotonin transporter, 5-HTT, are more likely to develop depression and to consider or attempt suicide than those who have the long version, according to Terrie E. Moffitt, a professor of social behavior and development at King's College London, and colleagues [Science, 301, 386 (2003)]. The serotonin transporter retrieves serotonin after it's been released into the synapse. SSRI antidepressants block this transporter.

WHERE ANTIDEPRESSANTS can block serotonin reuptake, stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines block dopamine reuptake, giving a pleasurable feeling that leads to addiction, says Karley Y. Little, associate professor of psychiatry and director of the Laboratory for Affective Neuropharmacology at the University of Michigan Medical School. As time passes, however, it becomes increasingly difficult for drug abusers to achieve a high. They tend to become depressed, possibly because the drug damages their dopamine transporters and levels of the neurotransmitter consequently drop. Brain tissue from cocaine users shows an apparently compensatory increase in the number of dopamine transporters on the neural cell surface at the synapse, Little and colleagues found [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 1 (2003)]. "Those cocaine users who upregulate their dopamine transporters the most are the ones who are most depressed."

Like dopamine transporters, serotonin transporters also adapt to being chronically blocked, Little has found. "We're interested in how that happens molecularly,<br > how that parallels symptoms and clinical problems, and"--with antidepressants--"if that is an important part of the therapeutic effect." Little has found evidence that the promoter polymorphism involved in Moffitt's study affects how much serotonin transporter a person expresses, as well as its reaction to antidepressants. "The big issue now is, does this matter or not? Are people who have one version of the gene more likely to get depressed, to commit suicide, to have a positive response to medication, or to have side effects?"

Advertisement

Gerard Sanacora, assistant professor of clinical neuroscience and director of Yale's Depression Research Clinic, is trying to determine whether the antidepressant effect of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors is due to their modulation of the release of two other neurotransmitters, -aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate, from "GABAergic" neurons.

Serotonergic neurons, for the most part, terminate on GABAergic interneurons, which are small neurons that link larger neurons, he says. "So there's good reason to think that serotonergic input could regulate GABA function."

A few years ago, Sanacora found that GABA levels in depressed patients were lower than those in healthy controls. "Since then, we've shown that treatment, either with electroconvulsive therapy or SSRIs like Celexa, causes an increase or normalization of this amino acid neurotransmitter in depressed brains," he says [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 577 (2003)]. Another recent study that Sanacora conducted shows that the GABA results most likely pertain to a subtype of those with depression: patients with melancholic or psychotic depression.

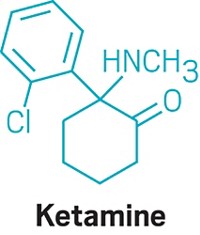

THESE PATIENTS also had elevated glutamate levels. Several pharmaceutical companies are working on antidepressants that target receptors for glutamate, Sanacora says. They include antagonists for NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptors and potentiators for AMPA (-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) and kainate receptors.

The GABA and glutamate systems also appear to be important in bipolar disorder. The anticonvulsants used to treat BPD may interact with these systems, according to Terence A. Ketter, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who heads Stanford University's Bipolar Disorders Clinic. Anticonvulsants with sedating profiles may increase GABA neurotransmission, whereas those with activating profiles may reduce glutamate neurotransmission [Ann. Clin. Psychiatry, 15, 95 (2003)].

BPD may involve abnormalities in other neurotransmitter systems. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region for the G protein receptor kinase 3 (GRK3) gene may contribute to the disorder, according to John R. Kelsoe Jr., a psychiatry professor at the University of California, San Diego [Mol. Psychiatry, 8, 546 (2003)]. Along with other research, "these data argue that a regulatory mutation in or near the GRK3 promoter causes this gene to fail to be expressed when dopamine stimulates receptors in the brain," Kelsoe notes on his website. "This results in an effective supersensitivity to dopamine" that leads to mood extremes.

University of Maryland associate professor of biomedical sciences Michael S. Lidow and colleagues believe that abnormalities in the brain's dopamine system elevate the level in the prefrontal cortex of dopamine receptor-interacting proteins (DRIPs) [Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 100, 313 (2003)]. These proteins modify and expand the functionality of dopamine receptors. Such abnormalities may be involved in schizophrenia as well.

Linkages between BPD and schizophrenia have cropped up in other work. For instance, brain samples show that expression of genes associated with myelin development is lower than nor- mal in both bipolar and schizophrenic patients [Lancet, 362, 798 (2003)].

Infections, particularly during pregnancy or early in a baby's life, may also link schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as well as serious unipolar depression. "The idea is that these infections might interact with the developing brain, presumably also interacting with genetic factors, to yield the disease state," says Robert H. Yolken, a pediatrics professor at Johns Hopkins University.

Yolken has found that "mothers who have evidence of infection with herpes<br > simplex virus type 2 (genital herpes) or of inflammation--as evidenced by increased cytokines--are more likely to have children with psychosis." The psychosis can take the form of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder.

Yolken published a paper [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 2234 (2003)] "suggesting that some individuals who get antiviral drugs show some improvement in their symptoms. That was in schizophrenia, but I think the study should be done in individuals with bipolar disorder as well." Yolken used the antiviral Valtrex (valacyclovir hydrochloride). Now he's doing a similar study using medications that fight Toxoplasma gondii, "a parasite that also appears to be implicated in some cases of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder."

Clearly, many mysteries remain in terms of understanding the causes of depressive disorders. Similarly, scientists don't fully comprehend how treatments for these disorders work. Nor can they tell who might respond best to a particular treatment.

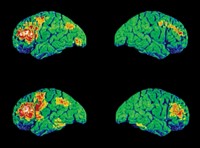

Doctors could better choose which of the wide array of treatments to use if they knew which ones were likely to work. Eventually, they may be able to use brain scans to make this determination. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) shows less activity in the anterior cingulate of depressed patients than in healthy controls in a test measuring reaction to visual stimuli that elicit an emotional response [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 64 (2003)]. Depressed patients whose anterior cingulate activity is mildly impaired respond more fully to treatment with Effexor (venlafaxine hydrochloride) than do those with more impaired activity.

Another study showed that those MDD patients whose pretreatment glucose metabolism is low in the brain's amygdala and thalamus and high in the medial prefrontal cortex and rostral anterior cingulate gyrus respond better to the SSRI Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) than other MDD patients do [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 522 (2003)].

Doctors would also benefit from knowing which of their patients would be more susceptible to the side effects of particular antidepressants. For instance, variations in the gene for the serotonin receptor 5-HT2a are suspected of affecting patients' vulnerability to some side effects. In a recent study, Greer M. Murphy Jr., an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, and coworkers provided further evidence for this hypothesis. They found that a single-nucleotide variation in the gene that codes for the receptor tripled the likelihood that a patient would stop a course of treatment with Paxil as a result of intolerable side effects [Am. J. Psychiatry, 160, 1830 (2003)].

Until such disparities are better understood, choosing the right therapy will remain an art. For now, doctors consider a patient's array of symptoms and vulnerability to side effects when they prescribe a pharmaceutical, psychotherapy, or other forms of treatment, such as electroconvulsive therapy.

If doctors could harness it, they might even find success using the placebo effect, which is a powerful one in depression treatment. About one-third of patients with major depression respond to placebo compared with about half who respond to the newer antidepressants, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, part of the Department of Health & Human Services. Relapse rates are higher with placebo than with antidepressant treatment, however.

A placebo can yield a clinical response that is indistinguishable from that seen with active antidepressant treatment, Emory University psychiatry professor Helen S. Mayberg and colleagues report [Am. J. Psychiatry, 159, 728 (2002)]. Inside the brain, however, the responses diverge. Mayberg's team found that patients treated with placebo or with Prozac (fluoxetine hydrochloride) showed a metabolic increase in the cortical region and a decrease in the limbic-paralimbic region. But patients given Prozac also showed brain-stem increases along with a drop in hippocampal and striatal metabolism, which "may convey additional advantage in maintaining long-term clinical response and in relapse prevention." The magnitude of change also was greater for Prozac recipients.

If doctors decide to use a pharmaceutical, they can choose from a wide array of treatments. The market for these compounds is huge, with antidepressant sales topping $11 billion annually, according to Bristol-Myers Squibb. Options include tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), SSRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs).

AMONG THE TRICYCLIC antidepressants are Elavil (amitriptyline), Norpramine (desipramine), Sinequan (doxepine hydrochloride), Tofranil (imipramine hydrochloride), Pamelor (nortriptyline hydrochloride), and Vivactil (protriptyline hy- drochloride). These drugs initially block reuptake of both norepinephrine and serotonin, which is also called 5 hydroxytryptamine (5-HT). Continued treatment also downregulates postsynaptic 1-adrenergic receptors. MAOI treatments include Nardil (phenelzine sulfate), Parnate (tranylcypromine sulfate), and Marplan (isocarboxazid). MAOIs block the oxidative deamination of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin, thus effectively increasing concentrations of those neurotransmitters.

SSRIs include Prozac, Zoloft (sertraline hydrochloride), Paxil, Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide), Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate), and Luvox (fluvoxamine). SSRIs block reuptake of serotonin, leaving more of the neurotransmitter available for pickup by postsynaptic receptors.

SNRIs behave similarly to SSRIs and include Effexor. NDRIs include Wellbutrin (bupropion hydrochloride).

Tricyclics and MAOIs were used primarily from the 1960s through the 1980s; they have since fallen out of favor because of their side effects, according to NIMH. Tricyclics cause dry mouth, constipation, bladder problems, sexual problems, blurred vision, dizziness, and drowsiness. Patients using MAOIs have to avoid some medications, such as decongestants, and some foods, such as cheese, wine, and pickles. High levels of tyramine in these comestibles can interact with this class of antidepressants to drive up blood pressure and cause a stroke.

SSRIs and medications that control neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine have fewer and less significant side effects, including headache, nausea, nervousness, insomnia, agitation, and sexual problems.

Advertisement

In addition to antidepressants, BPD patients must take mood stabilizers. Otherwise, their antidepressant treatment may push them into a manic episode or into rapid cycling between mania and depression.

The mood stabilizer lithium carbonate won Food & Drug Administration approval in 1970. Treatment with this compound has to be monitored closely because it can be toxic. Other side effects include weight gain, tremor, excessive urination, lowering of thyroid levels, and birth defects.

Despite these problems, lithium continues to be one of the most effective drugs available to treat bipolar disorder. In one study, risk of death from suicide was reported to be almost three times higher for bipolar patients treated with Depakote (divalproex sodium)--the most prescribed mood stabilizer in the U.S.--instead of lithium [J. Am. Med. Assoc., 290, 1467 (2003)]. Lithium was also found to be more protective than the mood stabilizer Tegretol (carbamazepine).

Other treatments used for BPD include the anticonvulsants Lamictal (lamotrigine), Topamax (topiramate), and Neurontin (gabapentin). So-called atypical antipsychotics such as Clozaril (clozapine), Zyprexa (olanzapine), Risperdal (risperidone), Seroquel (quetiapine fumarate), and Geodon (ziprasidone) can be used, as well as conventional antipsychotics, including Haldol (haloperidol) and Thorazine (chlorpromazine).

NEW AND BETTER drugs and formulations for depressive disorders are continually introduced. Forest Laboratories won FDA approval for the SSRI Lexapro, the S enantiomer of its racemic antidepressant Celexa, in August 2002. A year later, FDA approved GlaxoSmithKline's Wellbutrin XL, an extended-release version of the company's NDRI treatment for major depressive disorder.

In December 2003, FDA approved Eli Lilly's Symbyax to treat depression in BPD patients. The medication is a combination of the active ingredients in the firm's Zyprexa and Prozac.

Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka Pharmaceutical have submitted a Supplemental New Drug Application for the use of the schizophrenia drug Abilify (aripiprazole) to treat acute bipolar mania.

Few drugs have been approved for treating depressive disorders in children, so FDA is encouraging drugmakers to test their products' safety and efficacy in this population. A year ago, the agency approved the use of Prozac in patients aged seven to 17 for major depressive disorder.

Manufacturers are finding that they may need to be cautious with this patient population. FDA issued a public health advisory last October warning that a preliminary review of citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, mirtazapine, nefazodone, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine showed that the drugs might increase suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in pediatric patients with MDD. The agency continues to study the issue. The U.K. is urging doctors not to treat children under 18 with most SSRI antidepressants for this reason.

Those with depression can look beyond the pharmaceutical industry for help with the disorder. Natural treatments said to help depression and BPD include omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish oil), SAM-e (S-adenosyl-l-methionine), and the herbal supplement St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum).

Many people claim to find relief with these treatments, though the efficacy of such treatments remains unproven. St. John's wort, for example, "is no more effective for treating major depression of moderate severity than placebo," according to NIMH. To find out whether St. John's wort can help with minor depression, NIH is assessing its safety and efficacy as compared with Celexa and placebo.

Researchers at Stanford's Bipolar Disorders Clinic are also examining whether the ketogenic diet that is used for epileptics may alleviate depression in BPD patients. The diet is high in fat and low in carbohydrate, protein, and liquids.

ANOTHER ALTERNATIVE to pharmaceutical antidepressants is electroconvulsive therapy, also known as shock therapy. A patient is given an anesthetic and muscle relaxants prior to the procedure, which induces brief brain seizures by delivering an electric current through electrodes attached to the scalp. The patient receives up to a dozen treatments over three or four weeks, and follow-up treatments are often needed. Side effects include memory loss. Doctors still don't know how or why the treatment works, though it may reduce neuronal activity in some brain regions. Nor can they agree on its efficacy. Electroconvulsive therapy has gone in and out of vogue since it was introduced as a treatment for mental disorder in the 1930s.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is under study as a possible treatment for bipolar disorder at Stanford's BPD clinic, among other locations. This technique aims a magnetic field into the brain, creating an electric current in the prefrontal cortex. In turn, this depolarizes cortical neurons, as does electroconvulsive therapy.

If nothing else, the breadth of research under way into the causes and treatments of depressive disorders indicates how complicated the subject is. "The phenomenon of depression is probably extremely complex as far as what's going on in the brain," the University of Michigan's Little says. "It's not likely that one gene or one protein is the whole story."

But that very complexity offers numerous avenues for treatment of symptoms as well as possible cures. "We used to think of the brain as a computer, a hard-wired system, where once you lose neurons or a neural circuit, that's it, they're gone forever," Yale's Duman says. "However, now we know that the brain is much more malleable or resilient, and we're finding that even loss of neurons can be reversed. The brain is very adaptive, and it can be regenerated to a certain extent, which is of great hope for people who are depressed."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter