Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Insect Gardeners Rely on Chemicals

by Bethany Halford

September 26, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 39

CHEMICAL ECOLOGY

Two new studies provide insights into how insects and chemistry help plants survive and thrive. One report could bear fruit in the area of pest control for crops, while the other reveals the source of "devil's gardens" in the Amazonian rain forest.

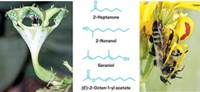

When faced with hungry arthropods such as spider mites and caterpillars, certain plants seek extra protection from an outside source. Once the herbivores begin to nibble away at their leaves, these plants produce volatile terpenoids that attract the herbivore's natural enemies--often carnivorous, predatory mites. The mites attack the feasting herbivores, thus defending the plant. This behavior has prompted scientists to nickname the predatory mites "bodyguards."

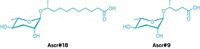

Of course, as anyone who cultivates homegrown tomatoes can attest, not all plants are chemically equipped to mount the bodyguard defense. Researchers at Wageningen University in the Netherlands and the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel, genetically engineered Arabidopsis thaliana plants with a strawberry gene so the plants would produce (3S)-(E)-nerolidol, a sesquiterpene that's been detected in mixtures of bodyguard-recruiting chemicals (Science 2005, 309, 2070).

In the past, scientists have tried, with little success, to engineer Arabidopsis plants to release these attractant molecules. The Dutch-Israeli team, led by Harro J. Bouwmeester, Iris F. Kappers, and Asaph Aharoni, succeeded by using the sesquiterpene-making enzyme to target the mitochondria. Earlier unsuccessful attempts had used the enzyme to target the cytosol or the plastids.

The new genetically engineered plants produced substantial amounts of (3S)-(E)-nerolidol as well as 4,8-dimethyl-1,3(E),7-nonatriene, another compound known to attract bodyguard mites. In lab tests, the bodyguards preferred the genetically modified Arabidopsis to the unmodified plant. The team notes that the transgenic plants' growth is similar to that of nontransgenic controls, suggesting that this type of genetic modification has the potential to protect crops against arthropod pests.

While chemistry prompts some insects to protect plants, other insects use chemical herbicides to secure their environment. Devil's gardens are large areas in the Amazonian rain forest made up of a lone species of tree, Duroia hirsuta. Local legend attributes the curious cultivation to an evil forest spirit, and scientists had thought the phenomenon was a result of allelopathy--a chemical process whereby one plant keeps another from growing too close. Now, Megan E. Frederickson and Deborah M. Gordon of Stanford University and Michael J. Greene of the University of Colorado, Denver, report that D. hirsuta's dominance of the devil's garden is actually due to ants (Nature 2005, 437, 495).

Formicine ants make their nests in D. hirsuta's stems. The team found that the ants use formic acid to kill any other plants that try to get a toehold in the devil's garden.

This report is the first to show that ants use formic acid as an herbicide, according to the Stanford group. The acidic gardening strategy seems to work well for the ants: Some of their colonies live as long as 800 years.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter