Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Anticancer Agents Found in Aged Wine

Compounds from oak casks react with wine components to form topoisomerase II inhibitors

by Stu Borman

October 31, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 44

Wine stored in oak barrels may be good for more than just the soul, researchers in France have found. Oak-aged wine contains bioactive compounds with the same type of activity and higher potency than a commercial anticancer drug.

Professor Stphane Quideau of the Research Center for Molecular Chemistry at the University of Bordeaux and coworkers recently found a new class of bioactive compounds in oak-aged wine-derivatives of multicyclic natural products called ellagitannins. The finding is potentially significant for wine drinkers because a substantial amount of wine is indeed aged in oak. A survey last year by Wine Business Monthly found that 5080% of U.S. wineries age their wine in oak barrels, for example.

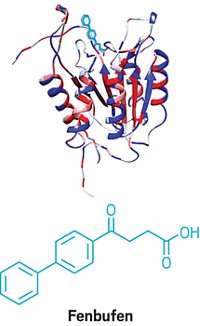

Some of the active compounds identified by Quideau and coworkers are more potent than the commercial anticancer agent etoposide, an inhibitor of the enzyme topoisomerase II (Chem.-Eur. J., published online Aug. 19, dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.200500428). A number of aged-wine components inhibit the same enzyme.

To jump to conclusions and say that drinking wine will protect people against cancer will be too much and not scientifically sound at this stage, Quideau says. We do not make such a claim, although the potential is definitely there.

Biologically active compounds have been found in wine before. For example, the phenolic stilbene resveratrol is rumored to have life-extending properties and is sold as a nutritional supplement.

This latest discovery of potentially healthy compounds in oak-aged wine is part of a flood of recent findings about the health effects of foods. In just the past couple of months, researchers have reported the following:

◾ Coffee is the number one source of potentially healthful antioxidants in the U.S. diet.

◾ A diet high in phytoestrogens, found in some soy products, grains, and vegetables, correlates with lower risk of lung cancer.

◾ Folate in leafy green vegetables and citrus fruit may protect against cognitive decline in older adults.

◾ Inositol pentakisphosphate, found in beans, nuts, and cereals, limits the supply of blood to tumor cells and inhibits tumor growth in mice.

◾ Isothiocyanate derivatives found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cauliflower block lung cancer progression in animal studies and in tests with human lung cancer cells.

◾ Pomegranate extract slows prostate cancer progression and decreases levels of prostate-specific antigen, a prostate cancer marker, in mice.

◾ Pomegranate extract also blocks enzymes that contribute to osteoarthritis.

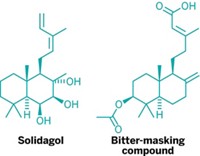

Quideau and coworkers now add to this cornucopia of findings by reporting that C-glycosidic oak ellagitannin derivatives in oak-barrel-aged wine have potent anticancer activity. C-Glycosidic ellagitannins are known natural products in oak. It now appears that they are extracted into wine during the aging process and then participate in nucleophilic substitution reactions with grape-based species found in wine, such as ethanol, flavanols, anthocyanins, and thiols. The resulting products include a number of topoisomerase II inhibitors, including -1-O-ethylvescalagin, two known acutissimins, two new epiacutissimins, vescalene, and (-)-vescalin.

Vescalin had been reported in earlier studies of plant extracts used in traditional Asian medicine. But its anti-topoisomerase II activity was not checked before, and through our evaluation, it turned out to be one of the most potent compounds, together with vescalene, Quideau says. He and his coworkers were also first to demonstrate that other anti-topoisomerase II ellagitannin derivatives, such as the known acutissimins, form in wine upon aging (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 6012). Their new study is a follow-up in which they report on the compounds' anti-topoisomerase II activities.

Most of the wine-related ellagitannin derivatives they tested were much more potent than etoposide at inhibiting topoisomerase II-mediated unraveling of DNA strands in vitro. This finding suggests potential antiproliferative activity and their potential use as new anticancer drugs, the researchers note.

Quideau and coworkers have filed a patent on the tumor cell antiproliferative effect of the compounds. They also have formed a partnership with Fluofarma, a biotech start-up based at the European Institute of Chemistry & Biology, in Bordeaux, to develop them. We are currently investigating whether these species can be used as catalytic inhibitors in specific types of cancer cell lines, or whether they could be used in combination with drugs for the treatment of various malignancies, Quideau says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter