Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

Women Faculty Make Little Progress

C&EN's annual survey again shows women underrepresented in top chemistry departments

by Corinne A. Marasco

October 31, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 44

Faculty Scorecard

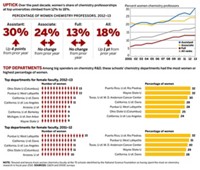

Once again, the only news about the percentage of women faculty members in the top 50 chemistry departments is that there is no news. For the sixth year in a row that C&EN has examined this topic, there has been little growth. Women are still vastly underrepresented among full professors, despite slow and steady progress between the 200001 and 200506 academic years.

C&EN surveyed schools identified by the National Science Foundation as having spent the most money on chemical research in 2003, the latest year for which data are available. The schools were contacted by e-mail and telephone and were asked to provide the number of male and female tenured and tenure-track faculty holding full, associate, and assistant professorships with at least 50% of their salaries paid by the chemistry department in the 2005–06 academic year. These numbers exclude emeritus professors, instructors, and lecturers, as well as any faculty and endowed professors whose salaries are not paid by the chemistry department. The response rate was 100%.

In academic year 2005–06, women represent 13% of the total chemistry faculty at the top 50 institutions. This increase comes after holding at 12% in 2004–05 (C&EN, Sept. 27, 2004, page 32), 2003–04 (C&EN, Oct. 27, 2003, page 58), and 2002–03 (C&EN, Sept. 23, 2002, page 110). In absolute terms, the total number of faculty positions increased from 1,594.5 last year to 1,633, and the total number of positions filled by women increased from 197 to 213.

One change to this year's analysis is the inclusion of the University of California, San Francisco, which was ranked first in terms of spending on chemical research on the NSF list in 2002 and 2003. Although the school does not have a chemistry department, its pharmaceutical chemistry department covers all of the fields a traditional chemistry department would. Therefore, it will be included in C&EN's survey from now on.

Other schools added to the list in 2005 are Emory University, Atlanta; the University of Delaware; and the University of Southern California. Schools that were on the list in 2004 but dropped off in 2005 are North Carolina State University, Wayne State University, and the University of Virginia. Together, those schools had 10 female chemistry faculty members, whereas the schools that replaced them have nine.

Among the schools that have the highest proportion of women in the total chemistry faculty, Rutgers University is still the top school, with 10 women, or 26% of the faculty. The University of California, Los Angeles, is second; its 10 women represent 24% of the faculty. Pennsylvania State University follows with six women, who make up 21% of the faculty. Massachusetts Institute of Technology is fourth, with six women, who account for 20% of the faculty. Purdue University and the University of Arizona are tied for fifth place; 19% of the faculty are women.

On the other end, just two schools on the list this year, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, have only one woman on their faculty. Nine schools have two women, and eight have three.

Women continue to be concentrated in the assistant and associate professor ranks. This academic year, women make up 21% of assistant professors, one percentage point higher than last year. Women's representation among associate professors is up to 21% as well this year; it was 19% last year. Women increased their share among full professors this year, to 9% from 8%. Looking back to the 2000 baseline, the proportion of women full professors has been increasing slowly, as has their share of total faculty positions. The proportion of women in the associate and assistant professor ranks has been more variable but has hovered around 20%. The set of 50 schools surveyed changes somewhat each year, however, so these variations should be viewed with caution.

In an effort to think creatively about the conditions faced by female as well as male professors, the American Council on Education (ACE) convened a conference in September as part of Creating Options: Models for Flexible Faculty Career Options, a project funded by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The conference, which included a national panel of 10 chief executive officers from major research universities and state university systems, focused on the need to reform and enhance the academic career path for tenured and tenure-track faculty.

The panel urged institutional leaders to act immediately to recruit the best faculty for tenure-track positions at research institutions, regardless of gender.

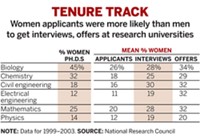

Women represent a substantial proportion of the faculty pipeline; however, women are less likely to pursue tenure-track faculty positions at research universities after earning their doctorates.

This condition is particularly true in science and engineering, where U.S. higher education cannot afford to lose any of its potential intellectual workforce and desperately needs the best talent in research and teaching, according to the panel. Talented scholars are necessary for innovative research and development to contribute to economic development of the country and to keep U.S. higher education in a competitive position worldwide, as well as for the country's security.

The panel strongly recommended changing the current rigid structure of traditional tenure-track faculty career paths. It suggested that universities create hospitable campus environments to support a diverse faculty, develop policies and programs that encourage flexible career paths to help faculty balance work and family responsibilities, and create flexibility in the probationary period for tenure review without altering the standards or criteria.

Advertisement

The executive summary of the conference report, An Agenda for Excellence: Creating Flexibility in Tenure-Track Faculty Careers, is available online at the ACE website (www.acenet.edu/bookstore/pubInfo.cfm?pubID=330). More information about the Creating Options project is also available on the website.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter