Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Salaries and Jobs

Chemists with jobs post solid pay gains, but prognosis for chemical job market remains murky

by Michael Heylin

November 7, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 45

The findings from the American Chemical Society's latest annual surveys of the salaries and employment status of new chemistry graduates and of its members in the domestic workforce are mixed, not unexpected, and not encouraging. And they come at a time when the overall job market is in the throes of some possibly profound changes that could bode ill for the working man and woman in the U.S.

Median starting salaries, as of last October, for chemists who graduated during the 2003–04 academic year were $32,500 for bachelor's, $43,600 for master's, and $65,000 for Ph.D.s. This put them all still below recent peaks-in constant 2004 dollar terms-of $36,700 for the 2000 bachelor's class, $47,600 for master's in 1999, and $74,100 for Ph.D.s in 2001 (C&EN, April 18, page 51).

Constant-dollar salaries for working chemists as a group have also declined slightly over the past three years. The median salary for all those with bachelor's degrees responding to the 2005 survey of $63,000 is down from $64,100, in constant 2005 dollars, for respondents to the 2002 survey. For master's, the parallel constant-dollar decline is from $79,700 to $74,000, and for Ph.D.s, from $94,200 to $93,000. At least part of this decline is due to a continuing dearth of relatively well-paying industry jobs, especially in manufacturing.

When viewed as individuals rather than as a group, chemists are doing better than this. Respondents to the 2005 survey who had not changed jobs in the previous year and who reported their salaries as of both March 2004 and March 2005 had a median gain of 5.0%-from $80,000 to $84,000. This followed a solid 4.3% increase the previous year. Salary gains measured this way include the impact of individual chemists' promotions and growing responsibilities (C&EN, Aug. 1, page 41). The 2004–05 increase for bachelor's was from $61,000 to $64,000; for master's, from $71,000 to $75,000; and for Ph.D.s, from $90,000 to $93,800.

Unemployment among workforce ACS members was down to 3.1% this March from the record high-over the more than 30-year history of the survey-of 3.6% a year earlier. However, the percentage with full-time jobs held at a record low, falling by a nominal 0.1% from the year-earlier level to 90.8%. The upturn in employment was in those with part-time jobs, up from 3.6% to 4.1%. Those on postdocs moved up by 0.1% to 2.0%.

The job market for new 2004 graduates was also quite weak. The 35% of bachelor's graduates, 53% of master's, and 40% of Ph.D.s with full-time jobs were all well below the levels for the 2000 class of 44%, 62%, and 50%, respectively.

The growth has been in the number of chemistry graduates who continue their education. The percentage of new Ph.D. graduates who are on postdocs has risen from 41% in 2000 to 52% in 2004. The percentage of bachelor's graduates who are in graduate school has also trended upward over the period, from 46% to 49%.

Both of ACS's annual surveys-starting salary and member employment-are under the purview of the ACS Committee on Economic & Professional Affairs. Since 1996, the member survey has been conducted by Mary W. Jordan, workforce specialist of the Office of Member Information. Janel Kasper-Wolfe, research associate with the same office, conducted the survey of 2004 graduates.

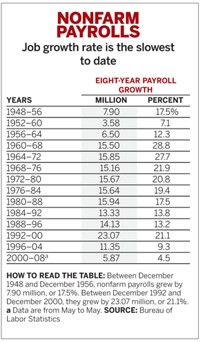

A mid-decade review of the exhaustive employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows that since 2000 the U.S. has suffered its weakest job market since the Great Depression. Depending on how employment is measured, over these five years, jobs grew either very modestly by historic standards or essentially not at all. This followed record or near-record job growth over the previous five years.

For each of the five half-decades between 1975 and 2000, total employment grew by an average of about 10%. From 2000 to 2005, it grew by 4.0%. For nonfarm payrolls, the parallel drop in growth rates was from 11% to 1.4%. For private payrolls, it was from 12% to 0.7%.

Total employment is estimated each month by BLS from a Bureau of the Census survey of households. Similarly, payrolls are estimated from a monthly Census Bureau survey of employers. The payroll total is always lower than total employment because it does not include farm workers, the self-employed, and much casual labor.

What all this means for the job outlook in general for the next half-decade is impossible to discern with certainty because a complexity of demographic, economic, and social factors come into play.

On the positive side, the job gains nationally that were posted between 2000 and 2005 mostly came in the past 12 months. So an upturn is now under way, if belatedly. And most of the renewed growth is in jobs for college graduates.

Of those employed and 25 years old or older, a growing percentage are college graduates-up from 28.6% in 1995 to 33.0% in 2005. They accounted for 62% of the increase in jobs for this age group over the decade.

On the negative side, the deficit of jobs generated by the unprecedented four years of little or no growth from 2001 through 2004 will take a long time to make up. Over these years, the workforce-those with jobs plus those actively seeking them-grew by close to 5 million.

Another issue is the erosion in the percentage of the population that is employed. For all those 16 years old and older, this number fell significantly from about 64.4% in 2000 to 62.3% in 2004, with a very slight uptick this year. For college graduates over 25 years old, this employment/population ratio fell from about 79% throughout most of the 1990s to about 76% this year.

Optimists claim this trend is a good sign because it indicates that more and more families can get by on one income in today's growing economy. This state of affairs is not likely. Private industry weekly earnings have been declining in constant-dollar terms for the past three years, and according to the Bureau of the Census, the number and percentage of families living in poverty has been on the rise since 2001.

Two other factors are of special concern for chemists. One is the possibility of a repeat of their delayed reaction, in terms of more jobs, to the record economic upsurge that started in the early 1990s and ran through 2000.

At that time, total private employment in the U.S. started to turn up in June 1991 and grew steadily for 117 months until early 2001. However, the employment situation for chemists, as measured by ACS's surveys, was weak in 1995 and did not really start to improve until 1997. Chemists fleetingly enjoyed only one really good year in 2001, just as the boom finally ended.

This time, the 2005 ACS member survey indicates little or no gain in full-time jobs for chemists between March 2004 and March 2005, whereas BLS figures indicate a respectable 2.1 million increase in total private employment for the period.

Also, the volume of classified advertising in the print edition of C&EN, a long-established quantitative indicator of the job market for chemists, remains stuck at a low level today. Activity on ACS's job website is increasing. However, it is not clear to what extent these gains are due to upgrading of the system in recent years.

The other factor is the extent of the recent precipitous decline in the number of manufacturing jobs. Over the past five years, they have fallen nationwide from 17.2 million to 14.2 million-a more than 17% decline.

If pharmaceuticals are excluded, chemical industry employment fell from 704,000 in August 2000 to 587,000 in August 2005. Pharmaceutical employment held up much better, with an increase of from 276,000 to 293,000 jobs over the same five-year period. But even here, the bloom may be off the rose: There's been no growth since early 2004.

Manufacturing jobs are still critical to the chemical profession. Forty-four percent of 200304 chemistry graduates who took jobs found them in manufacturing. And more than half-52%-of ACS's workforce members are still employed in manufacturing, with 15% in the chemical area, 22% in pharmaceuticals, and 15% with other manufacturing concerns.

Shifting demographics of the U.S. population will also influence the job market of the next five years. According to the Bureau of the Census, total population will grow from 295.5 million in 2005 to 308.9 million in 2010-a gain of 13.4 million. The number of children and youngsters up to 17 years old will increase only from 73.6 million to 74.4 million. Those of college age, 18 to 24 years old, will increase a little more, from 29.2 million to 30.5 million.

The only group forecast to decline-from 83.2 million to 82.8 million-is 25- to 44-year-olds. This could be good for them, as they will be in demand in any overall employment gain.

The 45- to 64-year-old cohort will grow the most-by 8.2 million, from 72.8 million to 81.0 million. This could make them somewhat vulnerable in the job market. They are the most expensive of employees, and even with a good economy, the number of jobs available to them may not grow as fast as the number of them will be growing.

Since World War II, there have been nine cycles in employment of big booms and little busts with long periods of solid growth followed by much shorter periods of downward adjustment.

For the first eight of these, as measured by private payrolls, the booms lasted an average of 66 months. The bust periods of actual job decline averaged 12 months. This decline was followed by an average 13 months to regain the previous peak-for a hiatus in overall job growth of 25 months. This pattern is very similar if measured in terms of BLS's data for total payrolls.

The latest downturn in private payrolls starting in 2001 lasted 29 months. It then took another 22 months to regain the 2001 level, for a total of 51 months before breaking back into new high ground.

The question is: Was this unprecedented hiatus in employment the result of a unique combination of factors, including the inevitable and unavoidable end of the 1990s boom, the spate of corporate scandals, the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and against terrorism?

Indeed, in light of all this, the economy and employment can be viewed as having held up pretty well since 2000. The gross domestic product (GDP) has been growing healthily since 2001, and with a few notable exceptions, corporate earnings are on the rise.

However, an alternative scenario is that something more fundamental is happening in the economy. The numbers are stark. Private payrolls grew by 17 million in the 1980s and by 20 million in the '90s. So far in the 2000s, they have grown by less than 1 million.

The disconnect between a solidly growing GDP and protracted softness in the job market is of concern. The perception is that the private sector, driven in some cases by unsustainable pension and employee health care costs, is tending less and less to regard its domestic workforce as an invaluable asset to be nurtured and used to its optimal capacity and more and more as an expense to be contained and reduced.

The next 12 months will be crucial. A solid year of job growth, building on the gains posted over the past 12 months, would augur well for many more years of job growth. On the other hand, an employment downturn would be serious. It would represent a second dip with no substantial job growth between-something that has not happened in the U.S. since World War II.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter