Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Too Cool for Titan?

Some are jaded about space exploration, but it's still worth getting excited about

by BY ELIZABETH K. WILSON

February 28, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 9

TERR

ESTRIAL ROCKS

The highlight of my weekday evening is Comedy Central's "The Daily Show" with Jon Stewart. I always look forward to Stewart's witty observations about international conflict and politicians' feckless behavior. So I was a tad disappointed when he treated last month's landing of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Huygens probe on Saturn's giant moon Titan with a cynical, blasé attitude he usually reserves for lampooning the business practices of Wal-Mart.

"Despite the project's seven-year time frame and $3 billion price tag, the Titan probe was able to transmit images for only two hours," Stewart snarked.

He's not the only one who was less than thrilled.

"Space exploration has gotten really boring," pop culture critic Peter Hartlaub whined in the San Francisco Chronicle. "It's hard to reconcile all the talk of mind-boggling discoveries when the pictures look like they were taken randomly from a car window during a drive from Barstow to Las Vegas."

Even my editor, a Ph.D. chemist, gave the probe's images of Titan's channels, hills, and shores a lukewarm reception. "They don't look that much different from Mars or Earth," he remarked.

Is it possible that we, living in a time where detailed close-ups of martian landscapes are available, might be getting jaded?

I'd like to think not. The initial public reaction to the Huygens landing was, in fact, huge. ESA reported nearly a million visitors to its website on Jan. 15, the day the probe landed. The event was anticipated in Time magazine and was on the front page of newspapers around the globe.

Meanwhile, other robotic space missions are keeping high profiles. The National Aeronautics & Space Administration's Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft, which carried Huygens on its journey to Titan, is eight months into its four-year orbit of Saturn. Its recent flyby of Titan yielded a photograph of a giant crater the size of Iowa. (Stewart's comments notwithstanding, it's the entire Cassini/Huygens mission, not Huygens itself, that costs $3 billion.) The Cassini mission websites are now getting even more hits than the Mars Exploration Rover mission sites, according to Guy Webster, spokesman for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which manages both missions.

And the Mars rovers and ESA's Mars Express spacecraft recently made complementary discoveries of widespread sulfur-rich gypsum deposits.

Yet there is a casual attitude toward planetary exploration in our popular culture that seems entirely new. It's hard to imagine anyone even venturing to assume a "been there, done that" stance about the fascinating, layered, water-addled geology discovered by the Mars rovers just a year ago.

There are key differences between the Titan and Mars missions, to be sure. Unlike the rovers Spirit and Opportunity, which are still trundling across the Red Planet a year after they landed, the Huygens probe was a one-shot deal, designed to survive just a few hours after landing.

And ESA, whose space missions have usually played second fiddle to NASA's formidable extravaganzas, is still learning how to best spotlight its publicity of Huygens.

But consider this: Titan is a wholly new, exotic frontier, nearly a billion miles away from us. It's the only moon in our solar system with an atmosphere. Titan's geological formations may look similar to familiar terrain here on Earth, but those objects in the photos aren't regular pebbles--they're water ice. That dark stuff covering those ridges? It's not ordinary dirt--it's a hydrocarbon goo. And what carved those channels? Not water, but liquid methane.

"I don't think it's likely that in the lifetime of anyone in the room we will repeat a landing on Titan," David Southwood, director of ESA's science program, said at the Huygens landing press conference.

And if that doesn't impress, consider the engineering it took just to get the probe to Titan intact: After directing Cassini on a nearly 3 billion-mile, seven-year ride, engineers put the spacecraft in the path of Titan's orbit, the moon barreling toward it. With radio commands taking more than an hour to reach the craft and probe, the team dispatched Huygens from the back of Cassini, then eased Cassini out of the way. Right on target, Huygens plunged through Titan's murky hydrocarbon fog, braked by parachutes and protected by a heat-resistant shield. Sampling the atmosphere and snapping pictures, and with only a 20-W lamp to illuminate its surroundings, Huygens came to rest intact in a soggy methane bog. It was, as Martin G. Tomasko, principal investigator for Huygens' descent images/spectral radiometer, noted, akin to photographing "an asphalt parking lot at dusk."

Though one of the two largely redundant channels of data from Huygens never made it to Cassini--the result of a human command error--radio telescopes on Earth were able to pick up faint signals from Huygens, allowing engineers to recover Doppler measurements of Titan's winds.

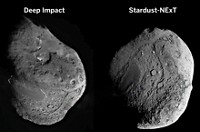

We can expect a lot more in the next few years: ESA's SMART-1 spacecraft is now orbiting Earth's moon, exploring its surface chemistry, and the Rosetta spacecraft will deploy a lander on a comet. NASA's Stardust mission is returning comet dust to Earth. Far from becoming ordinary events, each new mission should only increase our excitement about exploring the solar system.

We've still got a lot to discover before it's time to start yawning.

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter