Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Farm Emissions Control

Research aims to characterize and control odors and VOC emissions from livestock

by Sophie L. Rovner

September 25, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 39

What's the worst odor you've ever encountered? Outside a laboratory, the stinkiest smell I've had the misfortune of inhaling came from a pig farm. Research taking place at Iowa State University, Ames, could well put an end to such unpleasant sensory experiences. But odors aren't the only agricultural emissions of concern. Dairies, it turns out, are a significant source of smog-forming volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Studies at the University of California, Davis, are revealing the key types and sources of dairy VOCs and pointing to potential controls. Both projects were described during a Division of Agrochemicals symposium about agricultural impacts on air quality at the American Chemical Society national meeting earlier this month.

Jacek A. Koziel, an assistant professor in the department of agricultural and biosystems engineering at Iowa State, discussed his efforts to identify "stinky 'needles' in the chemical 'haystack' of livestock odor."

A typical air sample collected near a livestock operation "is extremely complex," containing "hundreds if not thousands of chemicals," Koziel told C&EN. Relatively little is known about the olfactory impact of specific odorants downwind from these operations, Koziel said. But what's clear is that "even low concentrations of very offensive odorants can be easily detected by neighbors far downwind of swine and beef cattle operations. We are taking a unique route of matching the chemical composition of air samples with the odor impact of specific compounds."

Koziel employed solid-phase microextraction to capture the odor-causing chemicals, which are often present at concentrations as low as parts per quadrillion or even less. This technique "works perfectly for air sampling at the source and far away where the odor is perceived as a nuisance," he noted.

Koziel analyzed the samples with equipment provided by Microanalytics, a firm in Round Rock, Texas, that specializes in aroma and off-odor analytical services and instrumentation. The firm custom-makes instruments that combine mass spectrometry and multidimensional gas chromatography capabilities with a "sniff port" and software for studying odor character and intensity. Multidimensional gas chromatography improves separation efficiency by running samples through both a polar and a nonpolar capillary column in the GC oven. It also allows the user to selectively "pull" specific odorants out of a mixture.

By sniffing the refined fractions that emerged from the instrument and combining that information with the GC/MS data, Koziel managed to identify the "compounds that are specifically responsible for the offensive character of livestock odor. We found that only a few compounds are responsible for livestock odor, regardless of the species," he said. "It's the same few compounds for swine, dairy cattle, beef cattle, or poultry."

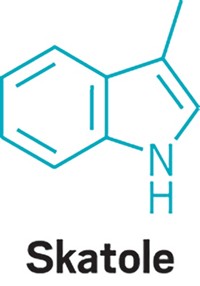

The guilty chemicals include isovaleric acid and hydrogen sulfide, which smell like old dirty socks and rotten eggs, respectively. But the principal odorant is p-cresol, which, at the low levels typically downwind of the livestock environment, has an offensive barnyard-like odor. "Of particular interest was the character-defining odor impact of p-cresol as far as 16 km downwind of the nearest beef cattle feedlot," Koziel said. Strangely enough, "the lower the concentration, the more 'barnyardy' it smells." Even stranger, at higher concentrations, p-cresol smells like a cleaning agent used for bathroom disinfection.

"While most of the separated compounds making up livestock odor are quite offensive and can be quite unpleasant for panelists working at the sniff port," Koziel told C&EN, "there are some aromas that we look forward to smelling. Some of them carry the specific smell of popcorn butter, freshly cut grass, or a wet taco shell." He was also intrigued to learn that "some 'benign' and 'pleasant' samples of coffee, honey, or lilac flowers have the same offensive odorants that cause livestock odor."

After Koziel identified the worst culprits in farm odor, he found that "if we remove just these key odorants, the air does not smell that bad anymore." He is studying practical and inexpensive ways to minimize the stinky compounds.

One method is biofiltration, which cleans air exhausted from a swine or poultry barn by passing it through a large bed of woodchips covered in bacteria. "The woodchips serve as a source of carbon and moisture for bacteria that thrive on the supply of odorous gases," Koziel said. "Literally, they are eating up these odorants, and the air that leaves the biofilter into the atmosphere is scrubbed clean of many odorous gases and dust." The only maintenance this inexpensive system requires is an occasional sprinkle of water to keep the woodchips moist.

Koziel said a number of these systems are being used in Iowa, Minnesota, and South Dakota. Koziel is working with Iowa State colleague Steven Hoff to optimize woodchip type and biofilter depth and age for the removal of odor as well as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and particulates that are of concern to regulatory agencies.

Other technologies Koziel is studying to remove key odorants include ozone and ultraviolet light. He is also evaluating whether commercial products that are marketed as odor-control agents for municipal wastewater can be used as manure additives. "Although livestock waste smells somewhat similar, it's a totally different matrix, so treatments that may be effective for municipal waste are often not effective in livestock systems," he cautioned.

Smelly compounds aren't the only concern for livestock operations. "In California, the dairy industry is believed to be the number one source of smog-forming volatile organic compounds," according to Frank Mitloehner, an associate professor and air quality extension specialist in the animal science department at UC Davis. "Dairies are considered even a larger source of VOCs than cars and trucks."

But "there was a lot of uncertainty whether the current VOC emission estimates for dairies are accurate," Mitloehner told C&EN. "So we were asked to conduct studies to find out what kind of VOCs come from animal waste, from animal feed, and from cows themselves by means of digestive processes" and in what concentrations these compounds are emitted.

"We found that very different compounds are emitted from dairies than was previously thought," Mitloehner said. Rather than volatile fatty acids, it turns out that "the most important VOC group in dairies is alcohols." In fact, he joked, "that's probably why California cows are so happy."

The main alcohols emitted from dairies are ethanol and methanol, and they're produced wherever organic material ferments. "Fermentation occurs basically everywhere on a dairy," Mitloehner noted. For example, it occurs in a cow's rumen, the first of the animal's four stomachs. The feed ferments inside the rumen, and when the animal belches, alcohols are released into the atmosphere. (Cow belching also releases a significant quantity of methane, which is a greenhouse gas but not a VOC.) Mitloehner was intrigued to learn that lactating cows release as much as six times the amount of alcohols through belching and other bodily emissions as nonlactating cows due to their higher metabolic rate and different diet.

Fermentation also occurs in the silage bags in which feed is stored, converting sugars into alcohols. In fact, fermented feed is one of the prime sources of VOCs at dairies, Mitloehner found. Although he hasn't yet finalized the data analysis from his feed experiments, he does know that emissions from fermenting feed can be an order of magnitude greater than emissions from fresh animal waste and other sources on a mass basis.

However, feed is generally stored under plastic in anaerobic conditions, so VOCs generated during fermentation aren't released until the feed is placed in front of cows. That means the actual dairy emissions of VOCs from feed are probably lower than that from fresh or stored waste, Mitloehner said.

Another significant source of alcohols in dairies is the drylot corral, where nonlactating cows are housed. Here, manure remains in the corral pens, and compounds have sufficient time to volatilize into the air.

Lagoons used for long-term storage of animal waste, which had been suspected as the largest source of VOCs, actually contribute very little, according to Mitloehner's research.

The lagoons have less of an impact on smog formation than expected because of the water solubility of alcohols, Mitloehner concluded. "Due to their water solubility, alcohols from waste stay in the lagoon water and don't go into the gas phase when the waste is washed into liquid storage facilities," he explained.

The finding that waste lagoons are only a relatively minor source of smog-forming VOCs is important because regional air districts in California originally decreed that dairies should cover their lagoons to prevent the gases from escaping into the atmosphere. Mitloehner said that step would cost the state's 2,000 dairies about $2 billion yet would have little environmental benefit. The new emission data will be used to revise dairy regulations, according to Mitloehner.

What practical and effective steps can be taken to reduce VOC emissions from dairies? Flushing waste out of animal housing and exposing it to water as quickly as possible improves capture of VOCs, Mitloehner said. Also, "one needs to think about which feed to use," he said. "We compared silage types, and there are large differences in emission potential from these different diets. The reason is that alcohol is an off-product of sugar fermentation. With a silage type that's low in sugar," only a small amount of alcohol is produced.

With the help of such modifications, California will be able to keep its sunny skies clear.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter