Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Proline Is Found To Prevent Protein Aggregation

by Sarah Everts

September 25, 2006

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 84, Issue 39

A small molecule that normally helps a cell survive dehydration can also prevent the formation of protein aggregates that lead to Huntington's disease.

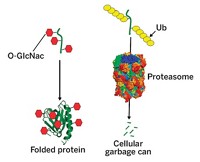

When a cell is exposed to salty conditions, or high osmolarity, water exits the cell, thereby increasing the concentration of proteins that are already in an extremely crowded environment. This stressful situation can lead to protein misfolding. To cope, the cell turns on a cell membrane pump that transports small molecules called osmolytes into the cell for damage control.

Given that osmolytes such as proline, trehalose, or ectoine help cellular proteins deal with stressful situations, biochemists at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, wondered if osmolytes could work in pathological situations-for instance, by helping to prevent aggregation in protein-folding diseases like Huntington's. Proline proved their hunch (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13357).

To test their theory, Lila Gierasch and Zoya Ignatova put together a protein chimera that favors partially unfolded states because it has a sequence of 53 glutamine residues attached at the end. Such strings of glutamine residues lead to protein aggregation and are the pathological agent of Huntington's disease. Using proline, the researchers blocked the unfolding-prone protein from forming aggregates and reversed the formation of small, early-stage aggregates in vitro and in vivo.

Proline works its magic by destabilizing an aggregation-prone intermediate, by breaking up small aggregates, and by stabilizing the native state of the protein, Gierasch said. The limitation is large, existing aggregates: Proline can prevent further accumulation but it cannot break up large aggregates, Gierasch pointed out. As such, using proline would be more prevention than cure.

Gierasch presented the work during a session of talks that celebrated her receipt of the Francis P. Garvan-John M. Olin Medal, which was cosponsored by the Divisions of Biological Chemistry and Biochemical Technology.

"Lila has shown very elegantly that one way a cell controls its folding environment is with osmolytes like proline. It's very nice work, very insightful," said Jeffrey F. Kelly, a protein-folding chemist at Scripps Research Institute, who also spoke at the session. "Proline prevents the aggregation of natively unfolded proteins, whose aggregation appears to cause Huntington's disease. Strategies that enhance osmolyte production could therefore serve to ameliorate aggregation diseases."

"Protein aggregation and misfolding reactions are also the bane of protein production and impede pharmaceutical drug development," wrote Mark T. Fisher of the University of Kansas in a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences commentary. He suggests that mixing proline along with other antiaggregation osmolytes such as trehalose could be used to "enhance everyone's protein-folding toolbox."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter