Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

The Economy, Demographics, And Jobs

The new economy, the leveling off of working-age adults, and the upsurge in new graduates will impinge on the future job market

by Michael Heylin

January 8, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 2

For the past 14 years, the U.S. economy has been on an exciting, but rather scary, roller coaster. The first eight of these years, 1992 to 2000, brought the longest and biggest boom ever in what is still, by far, the world's greatest economic power. The gross domestic product (GDP) built up to a very strong 4.1% constant-dollar annual growth rate from 1995 to 2000.

This situation was followed in 2001 with the inevitable recession. By historic standards, it was quite mild. Since then, the GDP has grown by a solid, if not spectacular, annual rate of about 2.5%.

So, what's scary? It's the story on jobs.

By one measure, employment hasn't done so badly. According to the monthly survey of a random sample of about 60,000 households conducted by the Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), total U.S. employment grew by an average of 2.3 million per year during the boom and by a still-reasonable 1.4 million per year since 2000.

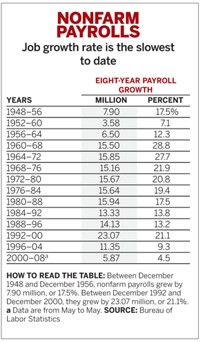

However, and of more significance to chemists, another survey paints a less promising picture. It measures nonfarm payrolls and is considered the most credible and meaningful indicator of employment. By this measure, 109.4 million people were on payrolls in 1992 and 132.5 million in 2000, for a gain of 23.1 million over the eight years. In the six years since 2000, however, payrolls have increased by only another 3.5 million, to 136.0 million.

In other words, total employment, which includes casual and other unrecorded labor, has held up fairly well. But the payroll jobs that chemists hold are lagging.

Another concern for chemists, most of whom still work for firms that make things, is the dramatic and sudden loss of manufacturing jobs. In 2000, 17.3 million people were employed in manufacturing of all kinds. By 2006, this number was down to 14.2 million. For the chemical industry, other than pharmaceuticals, the drop in total jobs has been, in round numbers, from 800,000 in 1992, to 700,000 in 2000, to 600,000 today.

These declines may be almost over, but the prospects for regaining the losses anytime soon are bleak.

Unknown is the degree to which current job market weaknesses are aberrations that will be smoothed out if there is a repeat of the traditional strong and prolonged upswing in payrolls that has followed all recent recessions.

This time, however, some things really are different. The U.S. is at war. An increasing number of jobs that could never be outsourced can be today, and even more may be tomorrow. And the philosophy that the golden key to business survival and success is to keep workforce costs as low as possible is becoming more rampant in the land.

Witness the immediate inflation alarms raised in the business press every time there is a new statistic that indicates that constant-dollar working salaries—which are still well below the levels of the past—have edged up a dollar or so.

Factors that will affect the employment situation and are more predictable include changes in the size and makeup of the workforce. The workforce comprises those with jobs plus those actively seeking jobs.

One factor is that the U.S. population will continue to grow by about 2.8 million per year for many years. This growth translates to the need for an average gain of a little more than 2 million more jobs per year just to keep up in the long run.

Changes within the population can vary enormously with profound effects. For instance, according to the Census Bureau, the U.S. population increased by 8.9 million during the 1930s. For the 1950s, this increase surged to 28.0 million. This gain, plus high birth rates in the late 1940s and into the early 1960s, is the baby boom and the source of a lot of serious economic anxieties today.

As the baby boomers retire in large numbers, starting about now, growth in the population of 20- to 64-year-olds will drop from 19 million during in the 2000s to 7 million in the 2010s and less than 5 million in the 2020s. The big growth will be among the young and especially the retired.

Another ongoing change is in the education level of the workforce. In 1975, 18.3% of working 20- to 64-year-olds had at least a bachelor's degree. By 2005, 32.5% did, including 33.3% of women.

With the number of college graduates continuing to rise, further gains are ensured in the caliber of the workforce, especially the female workforce. Today, women earn 57% of all bachelor's degrees, and this fraction will rise further.

So what's the prognosis for the U.S. workforce of 2020? In addition to it being better educated than it is today, it will likely be about 47% female, about what it is today. But women will be making solid gains at the higher job levels.

The bottom line, however, is that U.S. employment will keep up with the ever-growing population and workforce only if two things happen. First, American ingenuity must produce the potential to create enough domestic jobs in a flattening and increasingly competitive world economy. Second, business must invest in such jobs as it trends toward regarding its U.S. employees more as crucial assets and less as readily disposable liabilities.

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter