Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Big Biotechs Take Antibody Approach To Blocking Met Receptor

by Lisa M. Jarvis

August 20, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 34

The ubiquity of Met, a tyrosine-kinase receptor that helps a wide range of cancers proliferate, spread, and resist drugs, lends it strong commercial appeal. The pipeline is packed with small molecules that block the protein, but the major biotech drug companies are also rolling out their antibody expertise to interrupt the pathway of Met and its ligand, human growth factor (HGF).

COVER STORY

Big Biotechs Take Antibody Approach To Blocking Met Receptor

"It is harder to come up with a tumor type where there's no evidence of the involvement of Met and HGF than it is to find one where it is involved," says Terri Burgess, a director of research at Amgen. "And really, the only way to interrogate the pathway is with a very specific molecule like the one we have in patients."

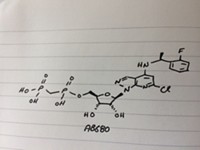

Burgess is referring to AMG 102, a fully human monoclonal antibody that came out of a collaboration between Amgen and Abgenix, which Amgen acquired in 2006. While all the other drugs in clinical development aim to block Met directly, AMG 102 works by neutralizing HGF, which is Met's only ligand.

"In many cases, there are multiple ligands for a receptor, so targeting only one wouldn't be a good strategy," Burgess points out. She notes that Amgen's drug also has a high degree of specificity for its target, a characteristic that could translate into an attractive safety profile.

Interim data from a Phase I trial of AMG 102 in patients with advanced solid tumors produced reasonable results. None of the 31 patients treated with the drug had tumor shrinkage of more than 50%, a result that some small-molecule inhibitors of Met were able to achieve. However, in 12 patients, the disease stabilized for more than three months, a significant result for a patient population that has exhausted all other avenues of treatment. The drug is now in Phase II trials against brain and kidney cancers.

Genentech, meanwhile, is using a "one-armed" antibody, OA5D5, to directly inhibit the Met receptor. For years, Genentech had also attempted to develop an antibody against HGF but found that it inadvertently activated Met in the process. When the firm tried antibody fragments instead, they blocked HGF without provoking Met, but the fragments cleared from the blood stream too quickly to be useful as drugs.

The solution, discovered by Ralph Schwall, a senior scientist at Genentech who succumbed to colon cancer in 2005, was to engineer an antibody with a single binding site. So, whereas currently marketed antibodies such as Genentech's Herceptin and Avastin grab their target with two binding "arms," OA5D5 makes a one-armed grab.

By using a single arm, the inhibitor appears to block Met without stimulating the protein and while retaining the favorable pharmacokinetic properties seen in two-armed antibodies. Genentech says the drug is in "the early stages of clinical development" for solid cancer tumors and will be the first one-armed antibody to be given to patients.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter