Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Molecules For Memory

Several companies are developing compounds that improve memory, but ethical issues abound

by Sophie L. Rovner

September 3, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 36

COVER STORY

Molecules For Memory

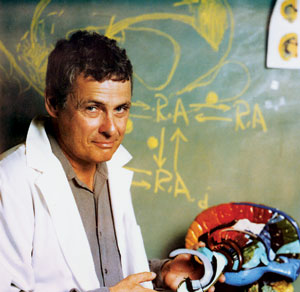

"MEMORY PROBLEMS in humans begin between ages 20 and 30, and they're progressive," says Gary S. Lynch, a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the University of California, Irvine.

An effective memory aid could get a warm welcome in our aging society, yet drug development has been slow. Only a few modestly effective drugs for treating memory problems associated with Alzheimer's disease are available, including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and Namenda (memantine), which blocks the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor on neurons. But "by and large, this is an untapped area," says UCLA neurobiologist Alcino J. Silva.

Many companies recognized the growth potential of the market and launched programs to develop cognition enhancers. Despite early enthusiasm for such products, however, the field "ran into molasses," because of the difficulties in pushing the drugs through the regulatory process, Lynch says. The main impediment has been convincing the Food & Drug Administration that it's acceptable to market this type of cognition-focused drug.

Tim Tully, a neuroscience professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, in New York, who cofounded the drug company Helicon Therapeutics, thinks there's a plausible way ahead for memory-enhancing compounds. If Helicon can show that one of its compounds helps Alzheimer's patients, Tully believes, FDA might then allow the company to evaluate the compound for a less severe condition called mild cognitive impairment. Ultimately, he hopes, the compound could be tested for age-associated memory impairment, "which is essentially what a large fraction of all 50-year-olds suffer from.

"Any people who are 50 or 55 and in the workplace would happily take a drug that could help improve their memory, because it would keep them competitive with the 30-year-old bucks who are vying for their jobs," Tully adds. "But age-related memory impairment is not really accepted as a medical need by FDA."

Lynch agrees that "the government is not in the business of saying you can go out and sell drugs to treat what is a normal condition." But what about Viagra? Lost libido and the other symptoms the drug is intended to overcome "are perfectly normal conditions of aging," he points out.

In the end, Lynch notes, "that says the government will probably recognize that it's okay to treat some of the other normal aspects of aging if we don't use the word 'disease.' "

If a drug is approved for older people, however, it's likely to end up in the hands of younger people, and not always for its intended purpose, Lynch acknowledges. "The Ritalin experience has sensitized the world to the possibility of off-label or recreational use" of drugs. Ritalin (methylphenidate) is prescribed for its calming and focusing effect in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but it's also a stimulant. "If you've got to finish your term paper tonight," Lynch says, "stimulants are going to help you do that."

Drugs that improve memory also conjure up a problematic divide between the haves and the have-nots. If "you have access to this drug and somebody else doesn't, and you're studying for an exam, you have an advantage over everyone else," Lynch says.

As society works through the ethics involved in enhancement, several academics and industrial researchers continue the hunt for compounds that can improve memory. UC Irvine's Lynch cofounded Cortex Pharmaceuticals to develop ampakines, which ease the process by which a long-term memory is created, also known as long-term potentiation. These compounds do so by enhancing the effects of glutamate on α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors on neurons (see page 13).

The first generation of ampakines spurs AMPA receptors to effect greater depolarization of neurons. That augmentation increases activation of the NMDA receptors that trigger long-term potentiation. Second-generation ampakines that are under development additionally prolong the opening of AMPA receptors, resulting in even greater NMDA activation. These newer compounds also boost production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). This growth factor is believed to increase production of new AMPA receptors and promote the growth and survival of neurons.

The compounds, several of which are benzamides, have been shown to improve memory in humans. Cortex is currently conducting a clinical trial of one of the first-generation ampakines in Alzheimer's patients, Lynch says.

Companies such as Memory Pharmaceuticals and Helicon are pursuing drugs that reduce the effort needed to form a long-term memory by enhancing activity of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor that's critical for memory consolidation. Memory consolidation is the process by which recent memories are stored for the long haul. Examples of these drugs include inhibitors of the phosphodiesterase PDE 4, an enzyme that normally reduces CREB activation.

Tully, who simultaneously with UCLA's Silva discovered CREB's involvement in memory consolidation, says Helicon is developing drugs that target a variety of steps in the CREB biochemical pathway. The compounds are all small molecules designed to cross the blood-brain barrier. Helicon is currently testing safety and dosage regimens in Phase II clinical trials of a PDE inhibitor in patients with age-associated memory impairment.

"The obvious patient to target is an Alzheimer's patient," Tully says, "but drugs that act on the CREB pathway should also be beneficial to treat many types of memory dysfunction." The drugs might help Parkinson's and stroke patients, for example.

Because of the early-reported successes of start-up companies such as Helicon, Cortex, and Memory Pharmaceuticals, Tully says, "several of the big pharmaceutical companies like Wyeth, Pfizer, and Merck now have programs that target this biochemical pathway. For instance, they now have PDE programs."

Plenty of other firms are looking into memory-enhancing drugs. Eli Lilly & Co., for example, has an advanced ampakine program, notes Graham L. Collingridge, a neuroscientist at the University of Bristol, in England.

IN ADDITION to compounds that interact directly with AMPA or NMDA glutamate receptors, researchers are targeting a third type of glutamate receptor known as the G-protein-coupled metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptor, Collingridge notes. Evidence suggests that activating a particular class of these receptors enhances the activity of NMDA receptors. Such compounds could treat cognitive deficits associated with conditions such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer's.

"At present, there's much less known about the fourth class of glutamate receptors, the kainate receptors," Collingridge adds. "But the available evidence suggests that they are involved in memory processes as well." He notes that his Bristol colleague chemical pharmacologist David E. Jane has developed potent antagonists that block glutamate from binding to a specific subtype of the kainate receptor. Collingridge and other researchers are now beginning to use these antagonists to sketch out the receptor's role in memory and other processes.

There are plenty of other potential targets in the brain. Nicotine, which enhances learning and memory, activates receptors for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Of course, no one is advocating smoking as a memory-enhancing technique, but researchers could conceivably create a nonaddictive nicotine mimic that would do the trick.

Until such drugs make it to the market, your best bet might be to swing by Starbucks. Karen Ritchie of the French National Institute for Health & Medical Research (INSERM), in Montpellier, recently discovered that memory function declines less over time in women who drink more than three cups of coffee per day, or the equivalent in tea, than in women who drink just one cup per day (Neurology 2007, 69, 536). Caffeine doesn't appear to offer the same benefit for men.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter