Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Rate Of CO2 Rise Accelerates

Economic growth and reduced uptake by ocean and land are responsible

by Bette Hileman

October 23, 2007

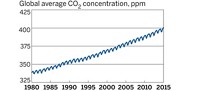

Release of CO2 due to human activity is increasing faster than ever while "carbon sinks"—CO2 uptake by oceans and land—are weakening, according to a new report (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0702737104). These conclusions are based on an analysis of data from CO2-monitoring stations around the world.

Human activities such as burning fossil fuels, cement production, and tropical deforestation added a net average of 4.1 billion metric tons of CO2 (measured as carbon) to the atmosphere each year between 2000 and 2006, the study says. As a consequence, the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere rose 1.93 parts per million per year during this period to reach 381 ppm. In contrast, average CO2 growth rates were 1.58 ppm per year during the 1980s and 1.49 ppm per year during the 1990s.

The current growth rate "is the highest since the beginning of continuous monitoring in 1959," according to the report, whose lead author is Christopher B. Field, director of the Carnegie Institution's department of global ecology at Stanford University. Recent emission increases have been "above the spectrum of any of the scenarios described by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change," he says.

The rapid rise in CO2 levels is primarily a result of three things, Field continues. First, the carbon intensity of the global economy has increased. Contrary to expectations, the amount of carbon, in kilograms, produced per dollar of global economic activity has risen recently, in contrast to the 1980s and 1990s, when the intensity fell. The intensity has gone up because most new power plants that have come on-line since 2000 are fueled by coal, the most carbon-intensive fuel, Field says.

Second, the ability of the oceans, especially the Southern Ocean near Antarctica, to absorb CO2 has declined, Field says. This conclusion is based on an analysis of data from Antarctic waters, which now have a higher concentration of carbon than in prior decades. And third, large droughts have reduced the uptake of CO2 by forests and other plants, he says.

"The new twist here is the demonstration that weakening land and ocean sinks are contributing to the accelerating growth of atmospheric CO2," Field says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter