Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Molecular Gastronomist Hervé This Tries To Define What We Eat

by Lisa M. Jarvis

July 7, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 27

The uninformed audience could easily mistake Hervé This for a country doctor. On the lecture circuit, the French scientist, known for his playful experiments with food, tends to carry a large leather medical bag that he mysteriously sets on the stage.

But instead of a stethoscope, thermometer, or bandages, out comes a whisk, a mixing bowl, test tubes, and a carton of eggs. He's like a modern day Mary Poppins; by the time he produces a mason jar containing an egg soaking in vinegar, This's audience—whether it's full of medical students curious about food or culinary students curious about science—is rapt and ready to believe anything can fit in his magical satchel.

Even more magical than his bag is what he makes out of its contents. In his demonstrations, This often whips up mayonnaise from egg yolks and olive oil in a beaker and then puts it in a microwave. The mixture balloons, then quickly turns into a solid. He upends the beaker to prove the density of the product. And voilá, he has produced a substance that can be spread like butter but tastes like olive oil.

This is a physical chemist at the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), in Paris, and the grandfather of "molecular gastronomy," a term used to describe the study of chemical aspects of cooking. In many ways, This's dalliance in food makes perfect sense; a physical chemist often tries to quantify observations made in the laboratory to come up with an equation to explain a physical phenomenon. This, meanwhile, is merely trying to come up with a scientific way to describe what we eat. The mayonnaise trick, for example, can be described as a two-step transition of two liquids to an emulsion and then to a gellified emulsion.

For the past 25 years, This has been collecting what he calls "precisions"—historical writings on the preparation of food. A piece about soufflé, which he found in 1980, sparked his addiction. That interest turned into a career spent contemplating the chemistry of ingredients and the physical transformations involved in cooking. To date, he has catalogued over 25,000 of his precisions, some dating back to the 1600s.

In addition to these collections, This has done his own experimentation, some of which is documented in "Molecular Gastronomy: Exploring the Science of Flavor." Much of his experimentation is serious stuff. His lab is well equipped for studying the physical properties of food and cooking, resulting in numerous publications in academic journals. His book explains the thermodynamics of a rising soufflé, and the level of detail devoted to the rate of protein coagulation will make you think twice the next time you boil an egg.

Sometimes his experimentation is simply about satisfying a curiosity. For example, when a colleague mentions that her salad dressing works better when the oil is mixed into the lemon versus the lemon being added into the oil, This will jot the observation down in a tiny notebook, adding it to a long list of food phenomena to explore in his lab.

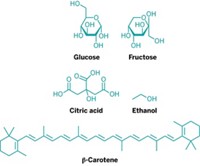

As part of his studies, This has devised a shorthand for describing food and dishes based on their physical states. An emulsion of oil in water would be described by "O/W," and the "formula" for making whipped cream by (O + S)/W + G →G/[(O + S)/W], where S and G stand for solid and gas, respectively. He's even built a machine in his lab—essentially a series of microreactors—to test his formulas by producing, in a controlled way, mixtures, dispersions, emulsions, and suspensions.

Some in the culinary world are up in arms about this technical, calculated way of describing and studying food. This has attracted his share of critics, many of whom collaborated with him in the early days of the molecular gastronomy movement. In 2006, renowned chefs Ferran AdriÀ, Heston Blumenthal, and Thomas Keller and food science writer Harold McGee printed something of a critical manifesto on the topic of molecular gastronomy in England's newspaper the Guardian.

The problem, McGee says, is that the term "molecular gastronomy," which first came out of a scientific workshop organized by This in the early 1990s, overemphasizes the science of cooking and underrates its art and creativity. Cutting-edge chefs like AdriÀ had long been using scientific tools in their kitchens, but this type of food "came out of the kitchen, not the lab," McGee says.

With their manifesto, the group seemed to want to underscore that they are interested in using technology to make food better or push the boundaries of taste, but not to make food preparation a primarily scientific pursuit, as they believe This intends.

Indeed, many other chefs whose work has been described as molecular gastronomy—Grant Achatz at Chicago's Alinea or David Arnold, director of culinary technology at the French Culinary Institute, for example—actually reject the term. "To me, molecular gastronomy means a cuisine that focuses on science—not a cuisine that uses science as a tool," Achatz says.

To his critics, This offers a rather obscene (and decidedly European) gesture. Molecular gastronomy is "only science," he says. "It's really just physical chemistry applied to the purpose of cooking." He seems frustrated and genuinely hurt by the derision.

Despite having attracted a handful of naysayers, This still captivates many food lovers. And France certainly adores its quirky culinary scientist; last month, the president of INRA presented This with the Légion d'honneur, an award akin to knighthood.

- Kitchen Chemistry

- Our love of food is helping bring science to the masses

- Formula Of Food

- Molecular Gastronomist Hervé This Tries To Define What We Eat

- Food For Thought

- A student finds a way to incorporate his love of science and food in his graduate work

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter