Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Olympic Air Quality Questionable

Athletes going for gold worry about Beijing's air

by Rachel Petkewich

July 28, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 30

BLUE SKY rarely peeked through the smog in Beijing at the turn of the millennium. So in 2001, when China's capital city was chosen to host the 2008 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games, the world wondered whether Beijing could clean its air in time for the arrival of the world's elite athletes.

Earlier this year, several athletes made headlines by saying they weren't going to risk their health and athletic careers by competing in an Olympics surrounded by polluted air. Other athletes suggested they would skip the opening ceremony, arrive in Beijing as late as possible, and wear face masks to avoid breathing outdoor air until moments before competing in their respective events.

China has reduced its pollution sources, but at press time, Beijing was still routinely shrouded in smoggy skies. Atmospheric chemists say the air quality during the Beijing Games literally rests on which direction the winds blow.

Scientists from China and other countries have been studying the air in preparation for the Olympics, and policymakers have been instituting standards to reduce emissions. The air pollutants of most concern for athletes and spectators alike are high levels of ozone and particulate matter, says Tong Zhu, an atmospheric chemist at Peking University, in China.

Both pollutants pose known respiratory hazards for athletes, and Olympic officials said last year that outdoor endurance competitions may be postponed or relocated if the air quality is particularly poor.

Particulate matter derives mostly from power plant and vehicle emissions. High summer temperatures, humidity, and nitrogen oxide emissions from cars promote photochemical formation of ozone. Beijing's average concentrations of particulate matter and ozone over the past five years have exceeded China's standards for similar cities and the stricter U.S. national ambient air quality standards.

Compared with those of the U.S. and Europe, China's atmospheric chemistry studies of ozone and particulate matter are in their infancy. "The notion that Beijing could have made its air permanently clean in seven years from the day it was awarded the Olympics was always a pipe dream," says Chris P. Nielsen, executive director of the China Project at Harvard University.

Hosting the Olympics has served as an impetus for China to make major changes in its infrastructure to clean up Beijing and surrounding provinces. Since 2001, for example, much of the energy infrastructure near Beijing has been switched from pollution-spewing coal-fired power plants to cleaner burning natural-gas facilities. A huge steel refinery was relocated outside Beijing and fitted with emission controls. The city overhauled its public transportation. Vehicle emission controls similar to European regulations have been instituted and strictly enforced. Beijing residents planted thousands of trees.

YET A RECENT STUDY by air quality researchers from China and the U.S. warned that just controlling emissions from Beijing will not attain air quality goals set for the Olympics (Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 480).

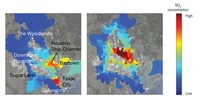

In the summertime, roughly one-third of the fine particles and up to two-thirds of the ozone in Beijing come from outside the city. The surrounding areas would have to cut their emissions as well to make a difference, says David G. Streets, an air pollution emissions expert at Argonne National Laboratory who worked on the study.

Therefore, in July before the competitions, during the Olympics in August, and during the Paralympics for elite disabled athletes in September, vehicles that do not meet stringent emission standards will not be allowed in Beijing, and many factories within hundreds of miles of the city are being temporarily shut down (see page 39). Because of these provisions, Streets is sure that air quality won't be as bad as last summer's or the summer before. "The question is 'Will it be good enough for the Olympics?' " he asks.

Many of the sweeping changes worked because China's authoritarian government ordered them. But the country's officials didn't account for the surge in China's economy that has occurred in the past five years or the fact that increased construction in preparation for the Olympic Games would undercut progress to reduce air pollution.

Construction dust aside, geography and weather may turn out to be the biggest challenges. Summer winds often bring to Beijing pollution from the south that lingers because of the region's position between mountain ranges to the north and west.

The Chinese government can't control the wind, but they may try to make rain. The China Meteorological Agency (CMA) has been flying planes that seed clouds with silver iodide particles to make rain since 1958, according to the agency's website. The Chinese could use the technique during the Olympics, for example, to prevent thunderstorms from disrupting the opening and closing ceremonies or to clean up the smog, says Russell R. Dickerson, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Maryland, College Park. Attempts to contact CMA for more detailed information went unanswered.

Some atmospheric chemists say cloud seeding could backfire. Even if the rain washes the particulate matter out of the air, ozone and ozone precursors, including hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides, remain. When clouds clear and the sun comes out, ozone levels could rise. Harvard's Nielsen says, "The Chinese government is much more focused on particles than ozone" because particles are visible, better understood, and "recognized as more deadly than ozone."

Beijing's blue sky may have looked inviting for the Aug. 8, 2007, celebration commemorating a year to go until the Olympics began, but it didn't look like that the day before. Luckily, the wind shifted the smog away from the city on the celebration day. This was exactly the situation that saved previous steamy summer Olympics in Athens; Atlanta; Seoul, South Korea; and Los Angeles from the burden of unhealthy air.

And fortuitous winds could blow again in Beijing. J. William Munger, an atmospheric chemist at Harvard, has studied China's air quality. He says, "Our measurements suggest that typical meteorology will help Beijing in August because the monsoonal flow from the ocean helps ventilate particles from Beijing and extensive cloud cover reduces ozone formation."

"Until then, scientists are just watching the weather along with everyone else," says Armistead G. Russell, professor of environmental engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology.

IN THE MEANTIME, naysayers have started to question whether air quality in China will continue to get better after the Olympics end. But Peking's Zhu asserts that "the improvement to air pollution will continue in Beijing after the Olympics because many measures taken now will have positive long-term impacts."

To follow up their initial Beijing air studies, Argonne's Streets says right after the Olympics and Paralympics end, he will again collaborate with the same scientists in the U.S. and China from their first project—plus a few National Aeronautics & Space Administration scientists with access to satellite data.

Streets and his colleagues will have access to the air quality data collected before and during the Olympics, along with details such as what actions to reduce emissions China actually took during the Olympics. About a year ago, China began internalizing its scientific studies and policy decisions related to air quality at the Olympics. Officials kept confidential all of their data collection and modeling, Streets says.

The Games present a boon for atmospheric science studies because emissions rates don't usually change that much in one place over an average three-month time frame, Streets adds. "It's going to be quite exciting."

Although the future of fledgling atmospheric science and policy in China will take decades to play out, the speculation surrounding whether some Olympic athletes will boycott the opening ceremony over concerns for their health will be answered starting next week. Let the Games begin.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter