Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Concocting A Crystalline Lair

Artist conscripts chemical phenomenon to create a shimmering blue realm

by Bethany Halford

January 5, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 1

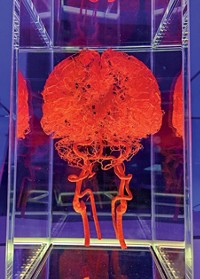

YOU MIGHT CALL IT Roger Hiorns' blue period. In "SEIZURE," his latest and most ambitious work, the 33-year-old English artist has taken a derelict London studio apartment and encrusted it floor to ceiling with brilliant blue copper sulfate crystals.

Although Hiorns has a penchant for unusual materials for arts—detergent, disinfectant, perfume, and fire have all been featured in his works—he says that he uses crystallization to give a natural phenomenon a hand in creating the artwork. "Copper sulfate is very useful as a material to stop me from having to make decisions on how something will look," he explains. "The crystallization process dictates its own aesthetic."

This isn't the first time Hiorns has relied on copper sulfate's crystallizing ways. He used the compound to overlay thistles and a BMW 8-series engine with a sparkly cerulean coating. Crystallizing an entire apartment, however, was something of a scale-up. After reinforcing the floor and ceiling and covering the ground-floor dwelling in plastic sheeting, Hiorns' team pumped 90,000 L—about 23,775 gal—of a supersaturated copper sulfate solution into the apartment through a hole in the floor of the apartment above.

"The wonderful nature of chemistry is that everything is very rigorous and everybody is focused on how things really work. That's how the science of it is," Hiorns notes. "This wasn't very scientific. We knew how to do this on a small scale in the studio, so we just made it a lot bigger."

With funding from the arts- and education-focused Jerwood Foundation, Hiorns and his crew purchased (and subsequently resold) all their equipment on eBay, including appliance-sized, 1,000-L stainless steel barrels for mixing the solution and industrial strength crude oil pumps for draining the copper sulfate supernatant. The group purchased 90 tons of copper sulfate, which is commonly used as a fungicide in Europe's wine-growing regions, from an Italian agricultural chemistry company. Remarkably, the project required no special permits or consultants, aside from an engineer who was called in to ensure the apartment wouldn't collapse.

Hiorns says he wasn't even entirely certain the crystallization would work. It could have turned out to be a mass of blue mush. "We had to sit on our hands for about three weeks just waiting for the solution to cool down," he says. The cool London summer turned out to be perfect for the experiment, gradually dropping the temperature in the apartment a degree each day. "We found when we drained the apartment that the crystals were far, far bigger than we anticipated," Hiorns says.

"The walls and ceilings are covered in blue copper sulfate crystals, their rhomboid facets glinting in the gloom," art critic Adrian Searle wrote in the Guardian newspaper. "Silvery shards of cold light spangle and wink and beckon. Every surface is furred and infested; big blue crystals dangle like cubist bats from the light fittings."

During its exhibition from September through November of last year, the installation drew more than 25,000 people to a soon-to-be-demolished housing complex near London Bridge. Only four people could enter the apartment at one time, so visitors stood in line for hours in a concrete courtyard as they waited to pull on rubber boots and see the crystalline cavern. Artangel, the organization that commissioned the work and that supports works that explore the relationship between art and place, described "SEIZURE" as "an extraordinary chemical intervention in the heart of the city."

Now that the exhibition has ended, Hiorns hopes to recycle the copper sulfate in some fashion, possibly as a fungicide or as an herbicide to kill invasive aquatic plants. Hiorns tells C&EN he is weighing the possibility of doing another large-scale crystallization. "Now we know how to do it, it seems perverse not to do it again," he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter