Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Materials For Adventure

New fibers and membranes make outdoor gear lighter and more comfortable

by Melody Voith

October 5, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 40

Todd Rutledge knows much more about advanced materials than the average apparel shopper. As a mountain guide in Alaska working under extreme conditions, he has good reason to be picky.

He recounts one memorable climb on North America’s highest peak. “I was on Denali, and we were waiting for snow conditions to improve on the West Rib route,” Rutledge recalls. “We decided that rather than wait, we would take the West Buttress Direct instead. This route had only been climbed maybe 10 times, ever, so no one really knew much about it. I underestimated the amount of time it would take for my client and me to climb it. We packed light, the bare minimum for eight to 10 hours—but it ended up taking us 18.”

An adventure that could have turned dangerous in the cold was merely tiring. “I was very thankful that I had a PrimaLoft-insulated jacket that weighed very little,” Rutledge says. Both climbers were wearing the same hooded jacket, made by Patagonia. “It extended our comfort range well into the night. It was light enough that we could move quickly, as we had a long way to go, but the insulation kept us warm enough at 16,000 feet at 2 AM.”

Rutledge has become a connoisseur of performance materials that will provide warmth, wind protection, and a moisture barrier while removing ounces from his personal kit. Recently, he has adopted a new type of layer: lightweight soft shell pants made with a Schoeller Textiles fabric. “They are so breathable and comfortable that I can wear them every day on a three-week trip,” Rutledge enthuses.

Every season, performance materials firms and outdoor gear manufacturers strive to sell a higher level of comfort to adventurers like Rutledge. Innovations can come from big firms such as Invista and Gore or from niche players that capitalize on the shortcomings of established brands. But finding a new material that gets high marks from both scientists and marketers is a tall order.

The market prospects for materials that do make the grade are considerable. High-performance outdoor apparel is a $9 billion-a-year industry, according to market research firm Plunkett Research. Founder Jack W. Plunkett tells C&EN that “water-resistant, wicking, lightweight, and versatile materials are top of mind for the market. I should know—I’m a skier and climber. I spend way too much money on gear.”

Furthermore, the outdoor gear market boasts strong growth and has not been much affected by the recession, according to Plunkett. “While the apparel market in general is dismal, active wear is holding up well. A lot of outdoors people are gear-heads and wouldn’t think of showing up on the mountain without the latest products from their outdoor magazines.” It is also one of the few noncommoditized corners of the textile industry.

The pace of innovation is swift and it is difficult for any material maker to stay on top. Rutledge knows that Primaloft is a top-of-the-line brand of insulation, as is its competitor, Climashield. But ultimately he trusts his favorite gear makers, like Patagonia and Black Diamond Equipment, to test out and incorporate the latest materials.

Among consumers in this market, “there is a lot of brand awareness about materials, which is unusual,” Plunkett observes. And material makers with strong brands can earn higher profits. The challenge, however, is to gain the attention of one of the few leading gear makers and get into their supply chain.

One firm that has been successful getting its materials—and its brand names—onto the bodies of outdoor adventurers is Invista, the one-time fibers business of DuPont that is now part of Koch Industries. “The outdoor and activewear segment is certainly one of our most strategic,” says Julien Born, Invista’s global segment director for activewear and outdoor apparel. “Customers are looking for our brands on hangtags to see what will sustain a comfortable temperature and manage perspiration better.”

Invista’s core apparel fibers are Thermolite and Coolmax, both made of polyester and used in the base layers of garments that are closest to the skin. Thermolite provides insulation from the cold with fibers that are made with a hollow core. “From the base technology, most development has been around improving the weight of the fabric,” Born says.

He describes Coolmax as a fast-wicking fiber with a cross-section shape that allows more air permeability and fast evaporation of humidity from perspiration, even under high-activity conditions.

Since weather conditions and activity levels can change rapidly, athletes are looking for garments that can be worn in warm and cold weather. Born says Invista’s newest fiber, launched this year, combines Thermolite and Coolmax. “Coolmax All-Season fabric is based on a fiber with a Coolmax cross section for evaporation and moisture management, but it also has a hollow core.” According to Born, the fabric can handle sweat but also keeps the wearer warm in chilly conditions.

To keep expensive gear from falling apart during the physical strains of an expedition, Invista makes a durable fiber called Cordura. Apparel, backpacks, stuff sacks, and boots made with Cordura have high tensile strength and can resist tears and abrasions. Today’s Cordura is an umbrella name for several products that began life as a so-called ballistic nylon developed for luggage in the 1970s.

To make Cordura, Invista extrudes nylon or polyester into long filaments, yarns, or shorter staple fibers. Then a proprietary texturing process gives the fiber its strength. In some versions the extrusion and texturing are handled in a single process called air-jet texturing, where yarn and water are sprayed from a nozzle in a high-speed jet of air.

Like many performance materials makers, Invista’s link in the outdoor gear supply chain is small: It makes only fibers. From its manufacturing sites, fibers go to a fabric mill to be woven, either on their own or in combination with other materials. Then the fabric journeys to a cut and sew facility, which works with an end-product manufacturer or retailer. Though the end product is several steps removed from Invista, it will carry the material brand name on its hangtag.

The long supply chain means R&D efforts fan out in many directions. “We have a dedicated team that goes out to the brands and brings back the voice of the customer for performance characteristics,” explains Cindy McNaull, global Cordura brand manager. “But we also have an R&D team at Invista looking at the molecular level to develop something that no one has even thought about yet.”

The military market shares some traits with the outdoor enthusiast market, and innovations can migrate between the two. McNaull describes a new wicking layer that Invista originally developed for the military.

“They were concerned about the polyester used in fabrics worn close to the skin. The heat of explosions from improvised devices can exceed the melting point of the fabrics, causing third-degree burns,” she recounts. Invista worked on a texture treatment for a lightweight nylon fiber and blended it with cotton to create a layer that would not melt, but was durable, comfortable, and quick-drying.

The next version of the product, called Baselayer, will have a silver-based treatment called freshFX. McNaull sets the scene: “When troops are out on their missions, they aren’t washing T-shirts in the Afghan desert. Anything you can do to reduce odor is an upgrade that they really love.”

Another tough fiber that has crossed from the military into the outdoor adventure market is DuPont’s Kevlar. “You’ll see manufacturers using Kevlar on the corners of a backpack where seams get damaged from rubbing” says Brian E. Foy, product design and development manager at DuPont Protection Technologies. It also appears in hiking boots, outdoor apparel, and motorcycle garments. For nonmilitary uses, Kevlar is usually used in combination with nylon to lighten the fabric and add abrasion, puncture, or tear resistance.

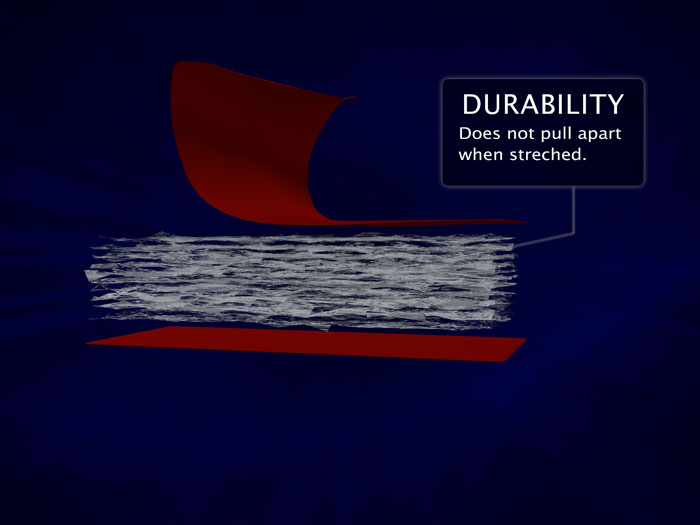

The overlap between military and outdoor recreation applications is not just for tough stuff. Both groups want to stay warm and dry in their jackets and sleeping bags and are pushing firms such as Harvest Consumer Insulation, which markets Climashield, to continually improve their products. Matt Schrantz, Harvest’s chief operating officer, says Climashield’s performance is because of its continuous polyester fibers. “Since we’ve never cut the fibers and we have a continuous filament, whatever weight we have has twice the loft. It is also tremendously durable, so it doesn’t come apart,” Schrantz explains.

But Harvest’s customers, from Patagonia and North Face to the U.S. military, are pushy. “You constantly have to bring new things to them or they will go out and find new things on their own,” Schrantz says. “The military has particular requirements, such as that the fiber has to be a certain diameter and thermal efficiency, even after washing 20 times. They want the sleeping bag to be the same size but twice as warm as they have today,” he says.

The pressure has made Harvest more competitive, Schrantz contends. He says new bags made with Climashield are lighter weight, smaller in volume, and have waterproof but breathable surfaces. “We put durable water repellant on it which drops the surface tension so the moisture transport rate goes through the roof. You can get in wet, wake up in the morning and be dry,” Schrantz boasts.

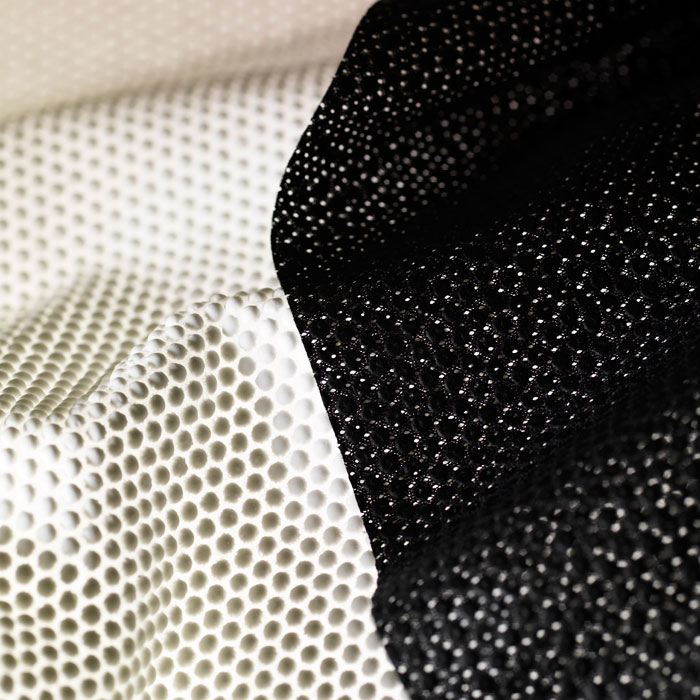

The push to reduce bulk and weight while retaining comfort goes all the way from innermost layer to the outer shell. Gore makes its Gore-Tex waterproof, breathable shell material with a membrane made from expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). The material’s small pores allow water vapor to move away from the body while keeping larger water drops out. The membrane is usually sandwiched between two other layers—an outer layer that protects the membrane from rips and tears and an inner one that protects it from damaging skin oils.

But a there is a new PTFE membrane on the scene, and it has garnered rave reviews from outdoor gear critics and manufacturers alike. BHA Group, a subsidiary of General Electric, makes eVent fabric, a breathable membrane that does not require an additional inner layer. Kansas City, Mo.-based BHA originally developed laminated venting membranes for industrial air filtration. “Then they looked for other businesses that could benefit and found a pretty significant outerwear marketplace that uses PTFE,” relates Glenn Crowther, global product line leader for GE Performance Fabrics.

The growing focus on green materials could haunt sellers of PTFE membranes, however. The fluoropolymer has been a subject of concern because its manufacture requires the use of perfluorooctanoic acid, which has been shown to persist in the environment and may be carcinogenic. Crowther acknowledges that the PTFE supply chain has issues. “As we get it in powder form, most of the PFOA has already been driven off,” he says. “We are staying current with what our suppliers are doing to replace PFOA as a processing aid.”

According to Crowther, the water vapor transmission rates of most PTFE membrane products are compromised by the inner layer that protects the oleophilic membrane from body oils. If the membrane becomes impregnated with oil, the surface tension alters, and water can seep in. But the extra layer dramatically slows the movement of moisture away from the wearer.

In contrast, the eVent membrane is oil-repellant and “a truly microporous material. Water vapor just moves right through it by diffusion,” Crowther asserts. The membrane is laminated to textiles, and the resulting eVent fabric is wind-resistant. Waterproof garments require an additional surface treatment.

So far, most of the equipment makers using eVent fabrics in their gear have been smaller European firms such as Germany’s Vaude, but in the past year, U.S.-based manufacturer and retailer REI has begun incorporating eVent into some jacket designs. While it waits for new consumer-market customers, BHA is busy developing applications for the military. Crowther says one new product, called eVent Active, includes a component made with a “decontaminating polymer that works in coordination with our membrane for chemical and biological protection applications.”

Advertisement

Schoeller Textiles wants to protect athletes from a much more common danger—the sun. The company worked with chemical industry partner Clariant to develop a fabric-finishing technology that reflects sunlight and protects the wearer’s skin from ultraviolet-A and ultraviolet-B rays. According to Tom Weinbender, head of Schoeller USA, the reflective quality of the treatment also prevents dark-colored clothing from absorbing heat from the sun. “Lab testing has shown that we get 10–15 degrees cooler on the body,” Weinbender reports.

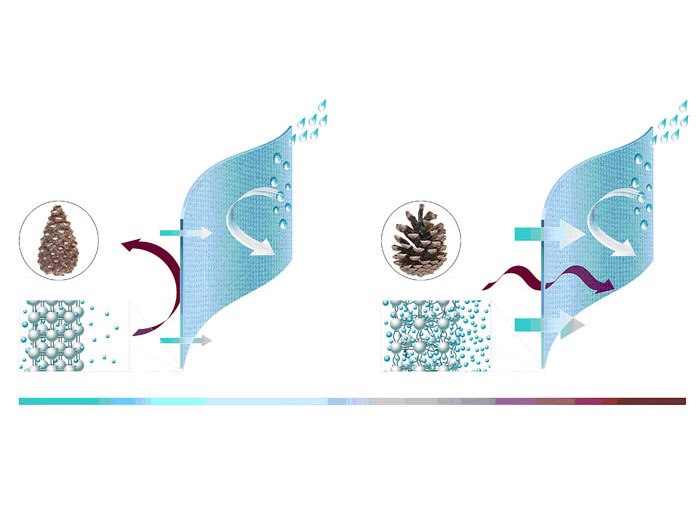

Like Gore and BHA, Schoeller has its own breathable waterproof material—a biomimicry of the way a fir cone opens and closes in response to different weather conditions. The membrane, called C-change, is made from a polyurethane that reacts to changing temperatures and humidity. “As temperature or humidity increases, the molecular structure of the membrane changes and it opens up” to release body heat and moisture, Weinbender explains. The response can be triggered by ambient temperature or by increased activity. Then, as the body produces less heat and energy, the polymer structure returns to its original position to keep the body warmer.

For another active material, Schoeller uses a concept originally designed for the National Aeronautics & Space Administration to moderate heating and cooling cycles on the space shuttle as it traveled from sun to shade. Encapsulated in the material is paraffin that absorbs excess heat when it melts and releases heat when it hardens. “We buy these capsules, mix them together with polyurethane foam and apply the foam filled with capsules onto a fabric,” Weinbender says. “We can put it in gloves, footwear, outerwear, ski jackets, and even bedding materials.”

Even the most exciting technical breakthrough can only succeed in the marketplace if it is embraced by people like Jeff Nash, director for materials development and testing at outdoor product maker the North Face. And he’s a tough customer.

“When someone comes to us with a product, we already know the landscape of each technology relevant to our business very well,” Nash says. “If we see opportunities in new technology, we review the company’s own testing, and we also validate it ourselves.” The North Face headquarters in San Leandro, Calif., has its own physical property test lab.

What performs well in the lab often fails under real-world conditions, so Nash is wary of any material until extreme athletes test it. “We do as much performance testing as possible, like for waterproofness, breathability, or odor absorption. We put it on our athletes or our in-house team here for daily use, he says. “They use new technologies for as long as possible, on multiple-day expeditions, very early in the process.”

Harvest’s Schrantz has seen the North Face testing regime in action. “A lot of our work is done in joint development. We make a proprietary insulation for the North Face that they helped us develop. They will put it in a new sleeping bag and come back with results for us.”

Similar testing has shown that phase change and other active materials have not worked well in the field. “We like the idea of active fibers, but the challenge we have is getting to commercial implementation,” Nash explains. He says phase-change materials and active fibers work excellently in lab conditions, but they don’t change fast enough to keep up with extreme athletes who shift rapidly between periods of high and low activity.

More promising in the near-term, Nash says, are the efforts under way to green the supply chain for outdoor apparel. Polyester from recycled bottles can now be used for the highest-end products because the yarns are very close to virgin quality. “We get much finer, stronger fibers, and much less chemical residue allows for better dyeing,” Nash says.

Invista’s Coolmax EcoMade is fabricated almost entirely from postconsumer bottles. Although the quality of the recycled polyester is improving, Born says, “you have to have checks all throughout the value chain” to make sure your raw material comes from a trustworthy recycled source.

Nash points out most consumers don’t realize that dye finishing is the most energy-,water-,and chemical-intensive process of apparel making. An independent standard for the textile industry, called bluesign, is helping companies clean up the supply chain. Manufacturers REI and Patagonia, and material and chemical makers Schoeller, Clariant, and Huntsman Corp. also work with bluesign standards.

In addition to greener manufacturing, Nash sees some exciting new technologies on the horizon, including new laminates for waterproof, breathable products. “Instead of a coating or traditional polymer film laminate, there are electrospun nanofibers laid together like a nonwoven material,” he says. The manufacturer can control pore size very precisely to balance water repellence and permeability. Manufacturers normally must trade one for the other, but Nash says the nanotechnology version can give higher levels of both.

To deal with material weaknesses caused by thread holes, seams, and other openings, Nash suggests that apparel manufacturers should think inside the box—a plasma treatment box, that is. With plasma surface treatment “you ionize the surface or entire finished product of a material in a high-pressure chamber, which puts your functional finish on in a durable, complete manner, he says. “You coat the threads, zipper, everything.” So far, Nash says, the equipment required for the treatment is the main barrier to commercialization.

Equipment makers and end users are looking to material makers to solve the vexing problems that remain for the extreme outdoors sports person. Nash would like to see materials with advanced cooling technologies for endurance athletes and mountaineers. Harvest’s Schrantz expects more laminates and membranes will unify several performance needs while reducing weight. Mountaineer Rutledge would like better abrasion resistance for his outer-shell garments. And for his backcountry ski adventures, he’d like to wear protective apparel that hardens on impact.

Rutledge has no doubt that new performance materials will come on the market at a fast pace. “It seems like the textile market is a crazy-competitive, fast-moving environment,” he says.

Schoeller’s Weinbender agrees. Outdoor gear makers—his company’s customers—travel the world looking for new technologies, he says. “We get many performance and design ideas from our customers—they are very consumer-driven.” Even a once-in-a-lifetime recession won’t slow down the North Face, Nash vows. “We’re already looking 12–24 months ahead for new technologies and materials to develop.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter