Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Philosophizing Chemistry

Philosophers delve into the central science

by Jyllian N. Kemsley

October 5, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 40

Philosophy as a discipline is an explicitly rational, logical, and critical way of examining fundamental questions of existence, knowledge, reason, and morality. The philosophy of science, in particular, reflects on the nature of science and how science works.

Philosophical questions go to the heart of how chemists communicate and conceptualize their subject and explore the limits of chemical knowledge—issues that are particularly important in teaching chemistry, said Jay Siegel, a chemistry professor at the University of Zurich. Siegel gave a talk on prebiotic chemistry at the International Society of Philosophy of Chemistry (ISPC) meeting, held in Philadelphia in August. Siegel noted that because no sentient being was around to observe the prebiotic world and there can be no fossil record, the philosophical questions about what kinds of things we ask, what we know, and how we know it are central to his research.

Although chemistry often brings up such philosophical questions, philosophers have tended to ignore the field in favor of physics and biology. Philosophers typically viewed chemistry as something that could simply be reduced to physics, said Eric R. Scerri, a philosopher and chemistry lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles. Also, “chemists are seen as more concerned with making molecules and not sitting back and philosophizing,” Scerri said.

In the past two decades, however, philosophers have increasingly turned their attention to chemistry, according to Michael Weisberg, a philosophy professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the organizer of the ISPC meeting. At the meeting, he and other philosophers of chemistry described how they are trying to better understand the underpinnings of the language and structure of chemistry, as well as the purposes and limits of models and other tools that chemists use.

Scerri, for example, described one area of philosophical consideration as defining the concept of an element at its most fundamental level: Is sodium, for example, that piece of gray metal stored in a lab, or is it something more abstract? It is more proper, perhaps, to think of elemental sodium as that thing that gives properties not just to the metal but also to NaCl and other compounds. Sodium may be best described as that abstract thing that you point to on the periodic table, defined only by its atomic number, Scerri said.

In a similar vein, Joseph E. Earley Sr., a professor of chemistry at Georgetown University, spoke about what it means to consider the properties of a molecule. Properties of composites are often considered to come from the properties of their components, he said, “therefore the components have been considered to be property bearers.”

But it’s problematic to think of molecules and their components that way, Earley noted. If one looks at the dye ruthenium red, for example, one sees a deep red substance that absorbs light at 532 nm. None of ruthenium red’s component parts has that characteristic. Or, considering the structure of a proton, the masses of its three component quarks add up to only 5% of the mass of the proton. The conclusion, Earley said, is that the properties come not just from the components but how they’re connected—just as a ham sandwich is not merely ham and bread but ham between two slices of bread.

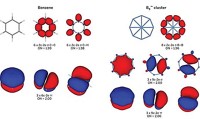

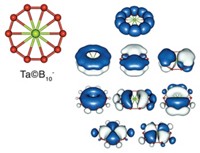

Philosophers’ ponderings of how molecules are connected then raises the philosophical question of what, exactly, is a bond. For all of the ways that bonds permeate chemistry—in standard structural notation for organic chemistry, in particular, most of what one sees are bonds—a bond is something that has never been directly observed. Experiments such as X-ray diffraction, for example, “give electron density distribution for molecules,” said Robin F. Hendry, who studies the history and philosophy of chemistry at the University of Durham, in England. Analysis of the topology then yields the chemical structure. Additionally, so-called facts about chemical bonding—bond energies, for example—are actually facts about energy changes between molecular or supramolecular states.

Bonds and chemical structures are, therefore, really models—a means of understanding complex systems. They, along with other models in chemistry, are simplifications that nonetheless have the advantages of visualization, generality, and the ability to serve as an aid to learning and problem solving, said Jeffrey Kovac, a chemistry professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The next question, then, Kovac said, is to decide what it means to give a scientific explanation or have a scientific understanding of a phenomenon such as a molecular bond or a chemical reaction. This involves deciding whether a model, or which of several models, will suffice, or whether it’s necessary to delve deeper—for example, when you can use Lewis structures or molecular orbital theory, or when you must do ab initio calculations.

Many of these questions are not new. “One of the frustrations of philosophy is that, in fact, philosophers are asking some of the same questions people have been asking for a long time,” and it’s not clear that there will ever be final answers, Kovac said. Nevertheless, in terms of both his research and teaching, “I think that at least for me some of the things that I have read in the philosophy of science or philosophy of chemistry have helped me to understand my science better.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter