Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Ancient Animals Leave Steroid Footprints

Molecular fossils push back earliest appearance of animal life

by Carmen Drahl

February 10, 2009

Gordon D. Love started out hunting for oil and ended up striking paleobiology gold. Together with an international team of scientists, he has unearthed chemical calling cards that constitute the oldest fossil evidence for animals.

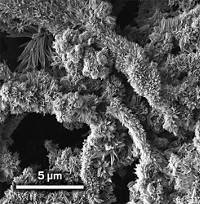

The earliest animals were soft-bodied creatures such as marine sponges, which don't leave skeletons for researchers to find. However, a class of modern sponges with ancient ancestors contains a distinct chemical signature, a series of 30-carbon biomarkers that arise when steroids in sponge cell membranes break down over time. Love, a geoscientist at the University of California, Riverside, found those hardy biomarkers, which are called 24-isopropylcholestanes, in rock that dates back 635 million years, trumping the next oldest evidence for animal life by tens of millions of years (Nature 2009, 457, 718).

Love and collaborators working in the research group of Roger E. Summons, a geobiologist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, made the find while helping a petroleum company locate oil, Love says. They analyzed hydrocarbons in sedimentary rock samples drilled at the southeastern edge of the Arabian Peninsula, which is home to rich oil deposits. The drilled rocks contain sedimentary layers, with each deeper layer coming from an earlier point in time, Love explains.

The team determined ages for certain layers of rock with uranium-lead isotope dating. They then extracted organic compounds from the rock and used a high-sensitivity version of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to study each layer's molecular signature. The 24-isopropylcholestane signature turned up among many other hydrocarbons in one of the deepest, oldest layers.

To ensure that the molecular fossils couldn't have migrated from younger rocks, Love turned to a technique called catalytic hydropyrolysis, which he helped develop in the 1990s. The method combines high-pressure hydrogen gas and a molybdenum catalyst to fragment hydrocarbons, including 24-isopropylcholestanes, off kerogens, which are insoluble mixtures of organic matter that can't migrate between rock layers. By using catalytic hydropyrolysis to identify 24-isopropylcholestanes in kerogens, Love and coworkers were able to "more confidently equate the age of our biomarkers with the age of the host rock," Love says.

Although the new find doesn't prove that these sponges were the very first animals, it does indicate that they thrived prior to the end of a great ice age called the Marinoan glaciation, Love says. "To me it suggests a change in ocean chemistry during the glaciation was important in the transition to animal life," he adds.

Kevin J. Peterson of Dartmouth College has independently estimated that sponges were around at the new, earlier date, but Love's work is the first experimental proof of his prediction. "Our work, in conjunction with the new study, suggests that if one were able to go back in time and bring back the last common ancestor of all living animals, it would resemble, quite closely, a modern bath sponge," Peterson says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter