Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Oxygen's Turbulent History

Geochemistry: Isotope studies reveal new details about the rise of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere and oceans

by Carmen Drahl

September 16, 2009

Primordial Earth had little oxygen in its oceans and atmosphere until two major spikes in levels of the gas occurred, paving the way for complex flora and fauna. The details surrounding those events are fuzzy, but two new studies of isotope records flesh out the story.

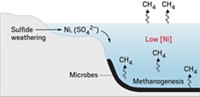

With nitrogen isotope data, Linda V. Godfrey and Paul G. Falkowski of Rutgers University reaffirm other groups' evidence that oxygen-producing bacteria, the probable cause of the first spike, were in the oceans long before it occurred. The researchers suggest that the first spike lagged behind the bacteria's appearance because the oxygen-producing bacteria's metabolism deprived the microbes of the nitrogen needed to substantially increase their numbers and the amount of oxygen they produced (Nat. Geoscience, DOI: 10.1038/ngeo633).

Meanwhile, Robert Frei of the University of Copenhagen and colleagues report a new way to study ancient oxygen: chromium isotope levels (Nature 2009, 461, 250). Their data imply that after the first spike, oxygen levels in the atmosphere fell back to lower levels before rising again, contrary to the prevailing view that the levels were always on the rise. "We are learning that the transition from an anoxic world to an oxygenated one was bumpy," says biogeochemist Ariel Anbar of Arizona State University.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter