Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Industry Adapts To Era Of Low Demand

Chemical firms cut costs and lowered expectations during a rough year for finances

by Assistant Managing Editor Michael McCoy, Senior Correspondent Marc S. Reisch, Senior Editor Alexander H. Tullo (all three in C&EN’s Northeast News Bureau), and Senior Correspondent Jean-François Tremblay (Hong Kong). Senior Editor Melody Voith (Washington, D.C.) collected data and coordinated the work.

July 5, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 27

All-around belt-tightening became the new reality for the world’s chemical firms in 2009. Chemical company executives shelved their strategies for growth and dusted off and implemented numerous contingency plans. With plants idled or running at historically low rates, firms looked for ways to streamline operations and increase productivity.

At U.S. companies Dow Chemical and DuPont, cost-cutting initiatives ran into the billions of dollars. But even smaller firms resorted to restructurings, plant closures, and layoffs. Many firms benefited from lower input costs for raw materials and energy, but then found it difficult to preserve margins when prices for chemicals also declined.

COVER STORY

Industry Adapts To Era Of Low Demand

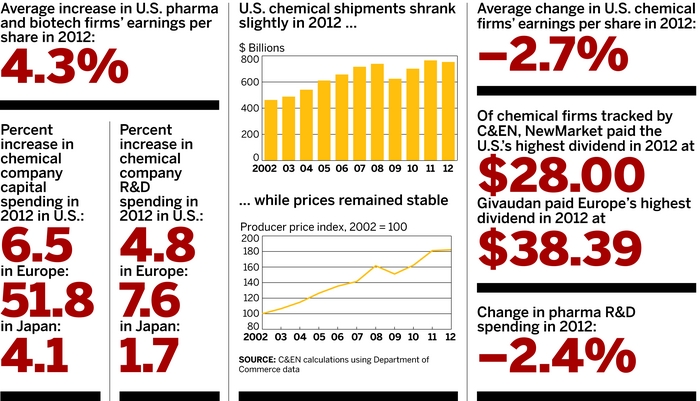

For a graphic depiction of how the recession hit the chemical industry as a whole, one need only look at the data on chemical shipments and prices. In North America, shipments toppled by 15.0% in the U.S. and a whopping 16.1% in Canada. Contributing to the decline were weak prices, which shrank by 6.6% in the U.S. and 5.3% in Canada. The lower prices reflect weak demand as well as lower energy and raw material costs. Still, the drop looks especially sharp compared with 2008, when U.S. shipments shot up by 9.6% and prices rose 14.4%.

In Europe, where the recession hit earlier during 2008 than in the U.S., chemical powerhouse Germany saw shipments retreat by 14.2% in a second year of decline that followed five years of steady growth. Of the countries tracked by C&EN, all shipped significantly fewer chemicals in 2009, but the 24% decline in the Netherlands was the most dramatic.

Unlike in 2008, chemical company executives were able to communicate their response to the ongoing earnings crisis in 2009. First-quarter financial results were foreshadowed with a raft of earnings warnings and press releases detailing cost-cutting measures. Many of the announcements used clever phrasing such as “we are working to reduce our business footprint” to hint at massive plant closings and layoffs. In the end, most firms were able to get out the word that financial results would be poor, lessening the punishment their stock prices took on Wall Street.

And the corporate news was, indeed, bad. In the U.S. and Europe, 2009 revenues declined at every chemical firm. In Europe, where the recession hit the hardest but also the earliest, many firms started to see a glimmer of a rebound in the second quarter. Some of them, including Belgium’s Solvay, Finland’s Kemira, the Netherlands’ AkzoNobel, and Switzerland’s Givaudan were able to wring more earnings out of meager demand in 2009 compared with 2008.

For most U.S. companies, earnings declined along with revenues. Dow Chemical was an exception; the acquisition of specialty chemical firm Rohm and Haas, though a risky move for Chief Executive Officer Andrew N. Liveris, brought high-margin businesses that cushioned the firm’s earnings. In Europe, BASF’s acquisition of Ciba did not have the same effect. In fact, BASF, the world’s largest chemical firm, saw its earnings sliced neatly in half for the year.

Interestingly, a number of U.S. firms saw earnings for the year fall less sharply than revenues. This was of little benefit to shareholders, who saw their earnings per share erode. But the cost cutting meant profit margins increased, leading some analysts to predict that the industry as a whole might be more profitable when the economy finally regains its footing. Companies in this category include Albemarle, Arch Chemicals, Celanese, Dow, DuPont, H.B. Fuller, Georgia Gulf, Lubrizol, NewMarket Corp., Praxair, Quaker Chemical, and Stepan.

In Japan, though sales were universally down, many chemical firms were able to stabilize their earnings—or at least narrow their losses—during the year. There was even one major acquisition as Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings expanded its dominion by buying Mitsubishi Rayon for $2.6 billion.

But what continued to trouble chemical company leaders was that it was unclear when demand would start to come back, and if it would ever again return to the golden era of 2007. The jobs picture continued to worsen, lagging behind all other barometers of economic activity and severely crimping consumer spending. And the easy credit that in years past fueled spending by both consumers and manufacturers appears to be gone for good.

One piece of positive news for the chemical industry was that the downward trend for demand leveled off during the second quarter. But after two full quarters of massive volume contraction, chemical companies continued to cut costs in the April-through-June period, leading finally to earnings improvement in the third quarter. And in the fourth quarter, stronger sales of automobiles, solar panels, and consumer electronics gave executives reason to hope that 2010 would look very different from 2009.

Meanwhile, the comparative strength of the Chinese economy impacted the fortunes of Western chemical firms both positively and negatively. Although developed-world companies were able to sell more products to China’s factories, they were forced in many cases to close down their own domestic plants because local demand was not enough to keep them running. And in contrast to previous recessions, analysts were unanimous in saying that many plant closures and layoffs in the U.S. and Europe would not be reversed even when the economy improves.

For the pharmaceutical industry, 2009 brought a very different set of troubles. Drug companies scrambled to expand earnings in the face of coming patent expirations for blockbuster drugs such as Pfizer’s Lipitor, Eli Lilly & Co.’s Zyprexa, and Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Plavix. Pfizer and Merck & Co. turned to mergers in an attempt to keep a supply of patented drugs flowing, and the combination of Pfizer with Wyeth and Merck with Schering-Plough also meant the loss of thousands of jobs for chemists.

The large pharma firms cut costs by killing projects deemed unlikely to progress. Spending on R&D by big U.S. drugmakers dropped almost 16% in 2009 after a decade of uninterrupted yearly increases.

Spending on research was also weaker at most U.S. chemical firms, though in most cases the decrease was small. Dow’s increased R&D spending was due to its acquisition of Rohm and Haas. Many European chemical firms, however, actually increased their spending on R&D in 2009. BASF boosted its spending for the year after retrenching a bit in 2008. Merck KGaA, Bayer, and Lanxess also spent more.

The bigger cuts came in capital spending. As a group, chemical firms in the U.S. and Japan cut back by more than 30%. In Europe, the decrease was about half that. With chemical plants still operating at lower-than-usual capacity, most chemical executives have promised to refrain from spending on long-term assets through 2011.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter