Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

People

Industry In The Ivory Tower

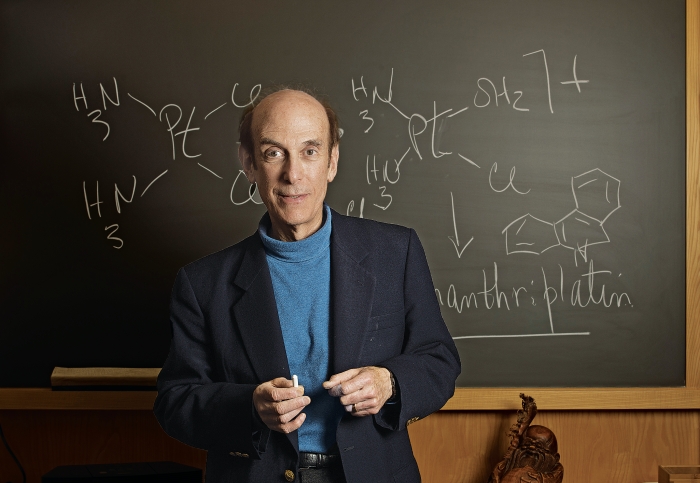

Ronald Breslow, a lifelong academic, garners the chemical industry’s big prize, the Perkin Medal

by Bethany Halford

September 27, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 39

A small and somewhat irreverent plaque welcomes visitors to the fifth floor of Columbia University’s Chandler Hall. It reads: “The Breslow Finishing School For Bioorganic Chemistry,” and it hangs just outside the suite of a dozen or so labs where for more than 50 years some of the finest chemists—bioorganic or otherwise—have toiled away under the tutelage of Ronald Breslow.

Plaques, usually signifying awards rather than inside jokes, are something Ronald Breslow has in spades. He’s won the Cope Award, the Priestley Medal, and the U.S. National Medal of Science, to name just a few. This week, he will add another honor to that list when he receives the Perkin Medal, an award from the American Section of the London-based Society of Chemical Industry.

The award recognizes outstanding work in applied chemistry that results in commercial development. It’s one of the chemical industry’s highest honors, and so at first glance it might seem an odd prize for Breslow, a lifelong academic.

“I was, at first, surprised,” Breslow confesses about his reaction upon learning that he’d won the prize. “I knew that the Perkin Medal normally goes to industrial people who have made some kind of major contribution.”

With research interests that range from the synthesis of the cyclopropenyl cation to artificial enzymes to the origin of chirality in biological molecules, Breslow admits, “I don’t think of myself as a chemist working on applied chemistry.”

But Breslow points out that he’s no stranger to applied chemistry either. He has been a consultant for the pharmaceutical industry almost as long as he’s been a professor. “I came to Columbia in 1956, and I think within a year I was consulting with drug companies,” he recalls.

That experience, Breslow says, was helpful when he founded his own pharmaceutical start-up, Aton Pharma, in 2001. It’s the chemistry that gave birth to and was developed at Aton that Breslow’s Perkin Medal recognizes.

The story actually starts in the 1970s, when Charlotte Friend, who was then a microbiologist and oncologist at New York City’s Mount Sinai School of Medicine, noticed that the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) had the power to turn cancerous red blood cells into healthy cells. In collaboration with Paul A. Marks, a cell biologist at Sloan-Kettering Institute, Breslow sought more potent compounds capable of performing the same feat. Ultimately, they discovered that suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, or SAHA, had the same cell-switching power that was observed with DMSO, only at much lower concentrations.

“The final drug we zeroed in on was not the most potent one,” Breslow says, noting that they found a Goldilocks sort of effect with the anticancer compounds. “The most potent compounds had problems with side effects, and the least potent ones weren’t good enough” at getting the cancer cells to switch to healthy cells, Breslow says.

SAHA “doesn’t poison or kill cancer cells. It actually modulates gene transcription” by inhibiting enzymes known as histone deacetylases, Breslow explains. It turns about half of the cancer cells it encounters into healthy red blood cells. “Once these cells start to turn into normal cells, they can’t go back,” he adds. “The other half of the cells go through apoptosis—programmed cell death” rather than succumb to SAHA’s action.

After raising nearly $100 million to complete preclinical testing, as well as Phase I and II human trials, Aton won approval for Phase III trials of the drug in 2004. At that time, Breslow says, the company’s board of directors decided to sell Aton to Merck & Co. to bring the drug to market. SAHA, renamed vorinostat and sold under the trade name Zolinza, has been approved as a treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the U.S., Canada, and some South American countries. “It was the first drug of its type to have been approved anywhere,” Breslow notes.

Research on SAHA-like compounds is still ongoing in the Breslow lab, but many others in academia and industry are also now exploring this type of chemotherapy. “What came out of this research is not just another drug,” Breslow notes, “but something that really has opened a huge field.”

Apart from his initial surprise, Breslow says he’s very excited to be receiving the Perkin Medal. “I think it’s wonderful, frankly,” he tells C&EN. He also believes that the award demonstrates that big pharma doesn’t assume they’re the only game in town when it comes to drug discovery. Companies are also interested in what’s going on in academic labs, Breslow says.

“Ron has made many contributions to the chemical industry, and what is especially unusual is how many different ways he has done it,” Stanford University chemistry professor and Breslow group alum Eric T. Kool notes. “For example, in developing the field of biomimetic chemistry, he came up with important ‘remote functionalization’ approaches to putting functional groups at specific hard-to-get-at sites on steroids, which became industrially useful.

“In some of his earliest work, he elucidated the mechanisms of catalysis by thiamin and other enzyme cofactors; some of these are used as catalysts today. In fact, he was one of the true architects of organocatalysis, a field that is burgeoning today both in academia and in industry,” Kool continues. “The breadth of his contributions is astounding, and it reflects a truly remarkable level of creativity.”

“I love the freedom to be able to pursue things that I think are interesting,” Breslow tells C&EN in his fifth-floor office one sunny September morning. It’s a large space, dominated by a meeting table in the center of the room and a chalkboard on one wall.

Breslow’s desk, where a newspaper Sudoku puzzle finished in pen rests, occupies one corner. A packed bookcase takes up one sizable wall, and Breslow’s own artwork, including a collaborative piece he made with the school’s glassblower, hangs among other personal and scientific mementos.

Throughout the morning, the buzz and pounding of construction work provide a score of sorts. There’s scaffolding outside the western window, where Breslow is about to lose his view to a new $280 million science building. The view, he says, wasn’t terribly great to begin with. And he’s happy to lose it to such an exciting project. The new structure will be home to Columbia’s new nanoscience center, of which Breslow is the chemistry director.

Breslow will celebrate his 80th birthday in March, an occasion that will be marked with a special symposium at the 2011 American Chemical Society spring national meeting in Anaheim, Calif. About 30 of Breslow’s former students will speak at the event.

“Most everyone has a wonderful sense of the seminal and field-defining contributions that Ron has made to the field of chemistry,” says Yale University chemistry professor Alanna Schepartz, a former student of Breslow’s and one of the upcoming symposium’s organizers. “But fewer know the depth of his contributions to the people of chemistry—his students and coworkers, of course, to whom he is the ultimate mentor, but also pretty much everyone else through his dedicated service and support of ACS.”

The birthday milestone doesn’t mean Breslow will be slowing down anytime soon, however. He currently holds the position of University Professor of Chemistry at Columbia, and retirement isn’t anywhere on his radar.

“It’s hard to imagine anything that’s more enjoyable than academic life,” Breslow says. “Eventually, I’ll figure out why I should retire, but I haven’t seen why yet.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter