Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

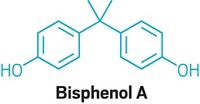

Scientists Find Bisphenol A In U.S. Food

Toxic Substances: BPA appears in meat, poultry, fish, vegetables, prepared food, and infant formula

by Kellyn Betts

November 1, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 45

The first data on bisphenol A (BPA) levels in U.S. canned, packaged, and fresh food to appear in a peer-reviewed journal have been published in Environmental Science & Technology (DOI: 10.1021/es102785d). The low parts per billion levels detected are in line with previous reports on food from other countries and by U.S. environmental groups, says Linda Birnbaum, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a coauthor. Whether the levels represent a concern, particularly for infants and small children, is under debate.

In light of the "large amount of information available from U.S. labs on other aspects of BPA safety, it is surprising that this is the first peer-reviewed study on BPA in U.S. foods," says Laura Vandenberg, a BPA researcher at Tufts University.

The new paper is a "market basket" study, says lead author Arnold Schecter, of the University of Texas School of Public Health. This type of study generally examines meat, poultry, fish, fruit, and vegetables purchased at supermarkets. The scientists included canned and packaged food in this study because the containers include BPA in their epoxy resins.

Olaf Päpke, a coauthor at Eurofins Scientific, an international group of laboratories that specializes in analyzing food and persistent organic pollutants, isolated the BPA and quantified it using high resolution gas chromatography and low resolution mass spectrometry. He detected BPA in many—but not all—of the canned foods, which generally had the highest BPA concentrations. Cans of Del Monte fresh cut green beans had the highest BPA concentrations in the study. Three cans contained between 26.60 and 65.00 ng of BPA per gram of food, which is equivalent to 26.60 to 65.00 ppb. Päpke also detected it in fresh turkey and in foods with plastic packaging, such as Chef Boyardee Spaghetti and Meatballs, which had higher BPA levels than cans of the same food.

Schecter and his colleagues calculated that the levels of BPA that children and adults consume from the foods in the study are below the Environmental Protection Agency's safety limit of 50 µg of BPA per kilogram of body weight per day. However, Vandenberg, together with others including Fred vom Saal of the University of Missouri, Columbia, contend that EPA's BPA limit is too high.

Epidemiological studies have linked human exposure to BPA with heart disease and diabetes in adults and abnormal behaviors in toddlers, Vandenberg says. Dozens of toxicology studies also connect BPA concentrations equivalent to the levels found in the U.S. population with a range of health problems, vom Saal adds.

On October 13, Canada added BPA to its official list of toxic substances, opening the possibility of regulating it. In January, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that it had "some concern about the potential effects of BPA on the brain, behavior, and prostate gland in fetuses, infants, and young children."

Although chemists have had a hard time formulating BPA-free can linings, the cans of tomato paste analyzed in the new study had non-detectable levels of BPA. Because acidic foods like tomatoes are known to enhance BPA leaching, the findings suggest that effective new linings exist and that companies are using them, says Ruthann Rudel of the Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit research group.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter