Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

More Dioxin Delays

Advisers say EPA needs to do more work on its draft report assessing the risks of the toxic compounds

by Cheryl Hogue

November 15, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 46

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa P. Jackson last year directed her organization to finish its reassessment of the risks from the most potent form of dioxin by the end of 2010. That analysis, which EPA began back in 1991, would update the agency’s current risk numbers, which date to 1984. Community groups have long clamored for the agency to complete this reassessment, an evaluation that will help guide cleanups of polluted sites in their areas.

But the agency will probably miss the deadline Jackson set, delaying the dioxin reassessment further. That’s because a panel of scientific reviewers from outside the agency says EPA needs to do more work on the most recent draft version of the reassessment, which was released in May.

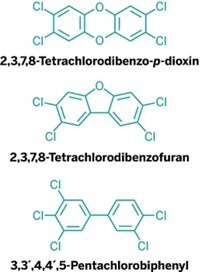

Specifically, the reviewers say that EPA should conduct an analysis that the chemical and paper industries have long sought. The results of this particular assessment are expected to produce risk numbers that would translate into less extensive and lower cost cleanups of dioxins, furans, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Companies that are or were major producers and users of chlorine are seeking to limit the liability they face for cleaning up sites contaminated with these compounds, which are often collectively called “dioxins.”

The reviewers—convened as the Dioxin Review Panel of the agency’s Science Advisory Board (SAB)—are stopping short of recommending that EPA use the results of this analysis for setting regulations, including cleanup levels. They say that good science demands that the agency do the analysis and compare its results with those of the risk calculation method the agency opted for in its most recent draft risk assessment for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD).

This chemical, which is the most toxic of the dioxins, is carcinogenic to humans and is linked to reproductive problems. TCDD is an unintentional by-product of the burning of wastes and of manufacturing processes involving chlorine. Industrial facilities have slashed their releases of TCDD and other dioxins in the past two decades.

In May, EPA released its draft document, which examines cancer and noncancer health risks from exposure to TCDD. In estimating the cancer risk from exposure to TCDD, the agency opted for what is called the “linear model.” This approach assumes that risk rises in direct proportion with dose and that exposure to any amount of the chemical could cause cancer. EPA used the results of high-dose experiments in laboratory animals to extrapolate risk for the significantly lower exposure levels found in the environment.

In an Oct. 27–29 meeting, SAB agreed that the agency needs to conduct a second type of analysis, with a tool called a threshold model. This approach assumes that there is a level below which TCDD does not cause cancer and, therefore, that some low level of exposure to the compound is safe. This analysis would produce lower risk numbers than the linear model and thus would lead to less stringent cleanup and other regulatory standards for TCDD and its chemical relations.

The advisers’ views echo those of the National Academy of Sciences, which reviewed EPA’s 2003 draft version of the TCDD reassessment. In its 2006 report, NAS said the agency should use both the linear and threshold models to estimate TCDD’s risks while describing the strengths and weaknesses of both approaches. Like NAS, the advisers on SAB do not intend to specify which of the two results the agency should ultimately use in calculating TCDD’s cancer risk for regulatory purposes. That policy decision is left to the agency, and according to the panelists, EPA could continue to conclude that its policies dictate a preference for the unsafe-at-any-dose linear approach for TCDD as a means of protecting public health.

EPA’s May draft document, which is the agency’s response to the NAS report, seems to focus on presenting evidence that supports use of the linear model rather than a balanced evaluation of alternatives, SAB panelist Harvey Clewell said. Clewell is director of the Center for Human Health Assessment at the Hamner Institutes for Health Sciences, in Research Triangle Park, N.C., and made his remarks at the end of the panel’s October meeting.

Another panel member, Jeffrey Fisher, a toxicologist for the Food & Drug Administration, asked whether a recommendation for a second risk estimation method will further delay the long-awaited TCDD risk assessment.

“Our job is to make sure the science gets done right,” responded Timothy Buckley, chairman of the panel and chairman of the environmental health sciences division at Ohio State University. Buckley called the recommendation for the second analysis “manageable.”

“We’re not asking them to start over,” Clewell added.

Arnold Schecter, panelist and professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Texas, Dallas, said that EPA’s taking a few months to revise the reassessment “seems indicated as necessary.”

“We want to see the assessment completed as quickly as possible, with the best science possible,” Buckley said. “The scientific issues are as challenging as they are important.”

EPA scientists who attended the SAB meeting indicated that they would start implementing the panel’s recommendations even before the advisers complete their official report in early 2011.

The requests “seem doable,” Rebecca Clark told the panel after hearing its draft recommendations. Clark is the acting director of EPA’s National Center for Environmental Assessment, which conducts chemical risk evaluations.

In addition, the advisers, like NAS, are asking EPA to conduct an uncertainty analysis of its cancer risk estimates. The agency’s May draft document says that it is not feasible to do this sort of analysis on the TCDD assessment. The advisers generally agreed that this argument is not scientifically justified.

“It really does need to be done,” Buckley said of the uncertainty analysis.

The panel also backed EPA’s classification of TCDD as carcinogenic to humans. However, the advisers were divided over whether EPA should include studies on dioxin-like compounds such as PCBs and furans when it calculates the cancer potency for TCDD—a move advocated by the chemical industry. Buckley said the panel might recommend that EPA take these studies into account in a qualitative, rather than quantitative, way to inform its analysis of TCDD.

The advisers’ discussions focused only on scientific details of the EPA draft report, not its policy implications. But the panelists aren’t unaware of the stakes riding on the outcome of the TCDD assessment. They got an earful about the report’s impact from the chemical industry, other business organizations, environmental groups, and a Texas regulator who spoke to them during a public comment session.

Joseph (Kip) Haney, a toxicologist for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, raised the specter that, if EPA ultimately sticks with the linear approach, the results would suggest that the U.S. food supply is unsafe and that mothers shouldn’t breast-feed their infants. The public’s main exposure to TCDD is through the consumption of beef, dairy products, pork, and fish, according to EPA, and the compound has been found in human milk.

Haney noted that the assessment will affect hundreds of sites contaminated with dioxins or PCBs, including areas that have already undergone cleanup to levels that are less protective than EPA’s May draft report would allow. The U.S. lacks sufficient disposal capacity for contaminated soil to meet a strict cleanup level, he said.

Representatives from local environmental groups urged SAB to finish its work swiftly so EPA can complete the long-awaited risk assessment. One was Laura Olah, executive director of Citizens for Safe Water Around Badger, a nonprofit organization working for environmental restoration of the now-closed Badger Army Ammunition Plant, in Wisconsin. The group is concerned about prescribed and accidental fires on military firing and training ranges that release dioxins. The longer the EPA risk assessment is delayed, the more service personnel, Defense Department workers, and communities around military installations will be put at risk from exposure to these compounds, Olah said.

David Fischer, assistant general counsel of the American Chemistry Council (ACC), an industry trade group, criticized EPA for taking a “piecemeal approach” to analyzing risks from TCDD and its related pollutants. In particular, he faulted the agency for its separate process to revise the toxicity equivalency factors that regulators use to compare the relative toxicity of PCBs, furans, and other dioxins with that of TCDD. Regulators use these conversion factors in assessing cleanup needs at a contaminated site.

Fischer also strongly objected to SAB’s five-minute limit on the oral comments made by the 43 members of the public who wished to address the committee.

Nonetheless, ACC was heavily represented among those commenters. In addition to Fischer, four consultants and a Dow Chemical scientist spoke on behalf of the group, and another consultant reported on work done at the request of the Research Foundation for Health & Environmental Effects, a nonprofit established by ACC. They each offered detailed scientific critiques of different sections of EPA’s draft document. In addition, ACC and its consultants offered many pages of written comments—on which there is no limit—to the SAB panel.

Joy Towles Ezell spoke on behalf of four Florida environmental groups and took aim at chemical manufacturers. “If the chemical industry had taken all the money and scientists and chemists and consultants that they put into delays of the EPA dioxin process over the last 20 years and instead put that money into technologies that would stop and avoid dioxins and other toxic emissions, the world would be a much safer and cleaner place,” she told the advisory panel.

“Every day, we continue to live with dioxin contamination in our neighborhoods, our foods, and our bodies while the EPA’s dioxin reassessment has been delayed,” Ezell added.

The SAB panel intends to finalize its report by February 2011, Buckley told C&EN.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter