Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

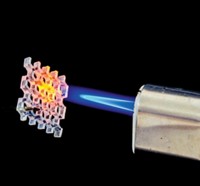

Fluoropolymer Processing Breakthrough

by Stephen K. Ritter

December 20, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 51

Poly(tetrafluoroethylene), or PTFE, best known for its use in DuPont's Teflon brand of products, has been around for 70 years. But it was only 10 years ago that Paul Smith, Theo Tervoort, and coworkers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, applied simple physical chemistry to solve a problem in PTFE processing. The team identified a narrow window of fluoropolymer viscosities that permits conventional polymer melt-processing extrusion methods to be used to make a wide range of molded PTFE products and spun fibers.

PTFE is a mechanically tough polymer with unique chemical-, thermal-, and mechanical-resistance properties. Since its invention in 1938, conventional and textbook wisdom has been that PTFE, unlike most other commercial plastics, couldn't be melt-processed because of the high viscosity of its molten state. It was thought that complex shapes such as machine parts could only be made by powder compaction, sintering, and subsequent sculpting of polymer blocks, or by adding a copolymer and fillers to allow melt processing, which is costly and diminishes PTFE's beneficial properties.

"We believe that our findings will cause a paradigm shift in fluoropolymer processing," Smith said 10 years ago. The researchers started a company, called Omlidon Technologies, based in Wilmington, Del., to develop the technology and license it to others.

The researchers moved ahead cautiously—and with good reason. "Much of the chemical industry feels that it got burned by early investments in advanced materials, and therefore many have elected not to pursue research on novel materials," Smith and Tervoort noted in 2000.

"We did not realize at the time how accurate our statement was," Tervoort now tells C&EN. "To our disappointment, no raw materials producer initially had the courage to step in to commercialize the technology," he says.

But in 2004, ElringKlinger Kunststofftechnik, one of the largest German-based fluoropolymer converters, was experiencing problems in fluoropolymer processing and realized the potential of the melt-processing development. Smith, Tervoort, and their team signed a licensing agreement, and since then "the company has been working hard to introduce this material to the market under the trade name Moldflon," Tervoort says.

Many of the anticipated applications, such as injection-molded PTFE bearings, films, tubings, fibers, and complex parts for the chemical- and food-processing industries and automotive applications—pieces that can't be machined—are now commercially available or at the end of their developmental stage, Tervoort says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter