Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

High-Speed Organic Electro-Optics

by Mitch Jacoby

December 20, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 51

Ten years ago, the University of Washington's Larry R. Dalton and coworkers turned to materials chemistry to boost the performance of electro-optic devices. The team designed a new type of conjugated organic chromophore and used it to fabricate high-speed electro-optic modulators, replacing standard inorganic crystals, such as lithium niobate, typically used in such devices.

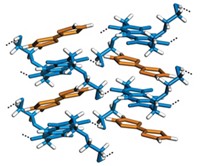

The key property of electro-optic materials that makes them attractive for light-manipulating applications is the ability to change refractive index with an applied electric field. To achieve that effect, the molecules must be aligned in a polymer or other matrix such that there is no center of symmetry.

"Our breakthrough came from understanding how to control the noncovalent interactions that guide lattice formation so that we could build supramolecular assemblies with architectures that are very rare in nature," Dalton says.

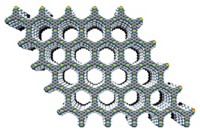

Putting that knowledge into practice, Dalton and coworkers designed a chromophore known as CLD-1 that features a bulky segment positioned between its electron-donating and electron-accepting moieties. The goal of that design strategy, which was derived from the team's computational analysis, was to overcome the inherent electrostatic interactions between the molecules that invariably drive them to align centrosymmetrically. It worked like a charm.

The devices Dalton's team made operated on less than 1 V and converted electrical data into optical information at rates exceeding 110 gigahertz. Similarly high data rates had been reported for other polymer-based devices prior to 2000, but those systems required much higher drive voltages, which affected noise levels and limited signal gain. High-speed, low-voltage devices are desired for applications in fiber-optic and satellite communication systems and for optical-switching technology.

The advances reported by Dalton's team a decade ago, which helped meet those application goals, were commercialized by a company called Lumera, based in Bothell, Wash. Lumera was later bought by Gigaoptics, a company with headquarters in Konstanz, Germany, that sells electro-optic devices for terahertz spectroscopy and other laser accessories based on Dalton's original discovery.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter