Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Emissions Controls May Cut Plant Aerosols

Atmospheric Chemistry: Reducing pollution may remove particles previously thought to be part of the natural background

by Michael Torrice

April 30, 2010

Reducing man-made emissions could decrease aerosols that come from plants, according to new simulations by scientists from the Environmental Protection Agency.

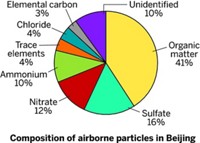

In the atmosphere, volatile hydrocarbons released by trees and other plants form hazardous particles called biogenic secondary organic aerosols. These aerosols can irritate people's airways and scatter sunlight to alter a region's climate. Because the particles' origins are natural, policymakers have considered them uncontrollable. But new simulations (Environ. Sci. Technol., 2010, 44, 3376) suggest that reducing man-made pollution could help manage these biogenic aerosols.

Atmospheric chemists have known for a decade that man-made or anthropogenic emissions provide ingredients to convert plants' volatile organic compounds into aerosols. For example, reactions with nitrogen oxides emitted from power plant smoke stacks can oxidize tree hydrocarbons. Aerosols form when these oxidized compounds condense onto particles, such as water droplets or carbon particles spewed from cars and trucks.

But no one had tried to quantify anthropogenic emissions' influence on the formation of biogenic aerosols, says research physical scientist Annmarie Carlton of EPA's National Exposure Research Laboratory in Research Triangle Park, N.C.

To estimate the anthropogenic contribution to biogenic secondary organic aerosols, Carlton and her colleagues simulated three weeks of air quality over the continental United States. In these simulations, the scientists fed EPA data on average daily emissions levels of plant hydrocarbons, nitrogen oxides, and other anthropogenic and biogenic compounds into chemical models of aerosol formation. After modeling the three weeks' actual air quality, the researchers simulated alternate scenarios with lower levels of man-made emissions.

When the researchers removed all anthropogenic emissions from their simulations, average biogenic aerosol levels fell by 50% in the eastern half of the United States, where volatile plant compounds and pollution are greatest. "Half of the biogenic secondary organic aerosol that forms in the atmosphere only forms when there is enough anthropogenic pollution around," Carlton says.

Average biogenic aerosol levels dropped by about 20% in most of the western half of the United States when the scientists removed man-made emissions. The simulations also pointed to so-called carbonaceous particulate matter, such as the carbon particles that cars and trucks emit, as the most influential pollutant type.

Atmospheric chemist Allen Goldstein of the University of California, Berkeley believes that the results show that the term "biogenic secondary organic aerosol" needs re-thinking. "As soon as the biogenic compounds react with anthropogenic pollutants, we have to ask if the label biogenic continues to be appropriate," Goldstein says. "It's biogenic carbon, but not biogenic aerosol."

Carlton and other researchers believe that the simulations could impact air quality policies. One of the pollution types that EPA regulates is particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers, which includes secondary organic aerosols. Policymakers have seen biogenic particular matter as untouchable, says atmospheric chemist Jose-Luis Jimenez of the University of Colorado, Boulder. "What this study shows is that that's not true," he says, "and that those aerosols should be part of those targets."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter