Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Nutrients Speed Oil Clean Up

Exxon Valdez Spill: Adding phosphorus and nitrogen to coastal sediments spurs biodegradation of lingering oil spill

by Sara Peach

September 9, 2010

More than 20 years after the Exxon Valdez spill, toxic crude oil still lingers on the beaches of Alaska's Prince William Sound. Now, researchers at the Environmental Protection Agency and the University of Cincinnati have demonstrated that adding nutrients to contaminated sediment has the potential to speed clean-up even at sites where most of the oil has already degraded (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es101042h).

When crude oil spills into the environment, natural forces such as evaporation, wave action, and consumption by oil-eating bacteria break down and disperse the substance. That process is called weathering.

Researchers have long known that adding nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, to a contaminated area stimulates bacteria to degrade the oil more quickly than under natural conditions. But previous research, conducted by Ronald Atlas of the University of Louisville and James Bragg of Creative Petroleum Solutions in Houston, Texas, suggested that the technique, called bioremediation, would have little effect at highly weathered sites where only small amounts of oil remain.

Albert Venosa and his team suspected that contrary to Atlas and Bragg's findings, bioremediation could be an effective tool for cleaning up lingering oil, says team member Pablo Campo-Moreno, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Cincinnati.

To confirm their suspicion, the researchers obtained contaminated sediment subjected to varying degrees of weathering from three locations in Prince William Sound. In a laboratory at the University of Cincinnati, they added phosphorus and nitrogen to the samples, and they replenished the nitrogen as it was used up. They tracked the degradation of the hydrocarbons present in the samples for 168 days, measuring at regular intervals using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry.

They found that the nutrient-amended samples biodegraded significantly faster than controls without nutrients, regardless of the degree of weathering. Importantly, they also found that samples from Knight Island, the most weathered site, had the highest degradation rate for total polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Their findings suggest that adding nutrients could be an effective treatment for the Valdez spill even where little oil remains. The next challenge, then, is to perform more tests outside of the laboratory, where low-oxygen conditions can limit biodegradation, says Michel Boufadel, a professor of environmental engineering at Temple University.

"We know that if you give oil enough oxygen and nutrients, it will biodegrade," Boufadel says. "One of the main challenges is to do it in the field."

A majority of the lingering oil in the Prince William Sound lies in the subsurface of the beaches, where it is protected from seawater by a layer of cobbles and boulders. Clean-up workers could introduce oxygen and nutrients to the subsurface by drilling wells or pumping in oxygen- and nutrient-saturated water. But scientists must first perform more research on the best ways to deliver oxygen while minimizing additional environmental harm, Campo-Moreno says.

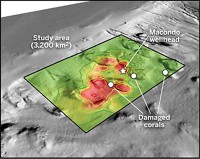

Meanwhile, researchers have their eyes on the Gulf, where bioremediation is under consideration for the Deepwater Horizon spill. Next month, Campo-Moreno and his colleagues plan to begin a new study on the biodegradation of spilled oil lingering in the deep Gulf.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter