Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Conserve Water To Reduce Arsenic In Rice

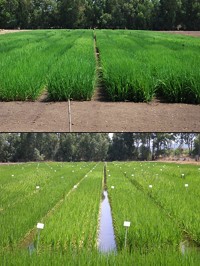

Water Pollution: Alternate wetting and drying of rice paddies in Bangladesh cuts arsenic contamination

by Janet Pelley

December 17, 2010

Rice is the staff of life for millions of Bangladeshis, but it could also damage their health. The well water drawn for irrigating rice in Bangladesh is naturally high in arsenic, a carcinogen with no safe dose. Now a study shows that a simple farming practice promoted to save water could also help cut exposure to arsenic (Environmental Science & Technology (DOI: Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es102882q).

Rice usually grows in perpetually flooded fields that provide a reducing and anoxic environment. In such an environment, arsenic becomes bioavailable and gets released from the soil. Plants can then readily take it up. Rice in a typical Asian diet can lead to daily arsenic exposures equivalent to drinking 2 L of water that is at or above the World Health Organization's limit for arsenic of 10 µg/L. Researchers have found that growing rice on dry fields cuts arsenic levels in the grains by 90% but also slashes yields.

A different farming method has been catching on fast in Bangladesh as a way to save water. In it, farmers irrigate their fields and then wait up to 10 days to let their paddies dry out before irrigating again. Stephan Hug, an aquatic geochemist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, and colleagues in Switzerland and Bangladesh wondered if intermittent irrigation could also lessen plant exposure to arsenic.

At a Bangladeshi rice paddy that is intermittently irrigated, the scientists measured the concentrations of arsenic and silicate in irrigation water and water trapped in the top 60 cm of soil. The researchers found that, compared to continuous flooding, alternating wet and dry cycles reduced plant root exposure to arsenic significantly throughout the soil, including a 75% reduction in the top 25 cm. What's more, Hug says, arsenic concentrations were lowest at the corner of the field farthest from the irrigation channel. Next, the researchers plan to measure arsenic levels in the plants themselves.

The researchers also found that silicate and arsenic concentrations peaked at the same depth in the soil. Hug thinks that elevated silicate could help cut arsenic levels in rice, because silicate competes with arsenic for uptake by plants.

"Alternate wetting and drying is a promising way forward to mitigate the problem of arsenic in rice," says Andy Meharg, a biogeochemist at the University of Aberdeen. Short of preventing arsenic from reaching rice crops, Hug says, irrigating as little as possible and not planting near irrigation inlets may be the best strategies.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter