Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

People

Ralph F. Hirschmann Award In Peptide Chemistry

Sponsored by Merck Research Laboratories

by Bethany Halford

January 3, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 1

It’s easy to imagine how pursuing studies in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy could doom a scientist to a career spent chained to a spectrometer in some cool, dark, instrument lab. But that hasn’t been the case for David J. Craik. In his quest to discover and study the cyclic peptides known as cyclotides, you’re just as likely to find Craik, 55, scouring the Australian countryside or African plains for plants as you are to find him locked up with instrumentation.

“We’ve had a lot of adventures,” Craik tells C&EN of his search for cyclotides. Consider, for example, the time his lab drove through the Australian desert from Brisbane to Alice Springs, carrying all the food, water, and fuel needed for the five-day journey. “It takes skills other than chemistry,” observes Craik, who is currently a Professorial Fellow at Australia’s University of Queensland.

But it’s Craik’s sense of scientific adventure that’s being recognized with the 2011 Ralph F. Hirschmann Award in Peptide Chemistry. “Professor Craik has made outstanding contributions to our understanding of the structure-function relationships of peptide toxins and circular peptides and proteins,” notes Paul F. Alewood, Craik’s colleague at the University of Queensland. “His multidisciplinary approach not only requires great intellect and drive but courage to learn new disciplines and employ them in smart ways.”

A native of Australia, Craik earned bachelor’s and doctoral degrees from La Trobe University, in his home country. After postdoctoral stints in the U.S. and back home, he joined the faculty at Australia’s Victorian College of Pharmacy. In 1995, he moved to the University of Queensland.

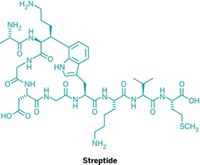

It was during a sabbatical at England’s Oxford University, in 1991, that Craik discovered the first cyclotide—a cyclic peptide with six cysteine residues in a knotted arrangement. The protein, named kalata B1, had originally been identified in the 1970s by Lorents Gran, a Norwegian doctor who isolated and identified the compound as the active component in a tea that women in the Congo drank to shorten their time in labor.

“It was a complete accident that I came across this peptide,” Craik recalls. “I did the structure using NMR and we discovered the knotted disulfide arrangement and with colleagues discovered it was a head-to-tail cyclic peptide. No one had seen a cysteine knot before, and a head-to-tail cyclized backbone for a peptide of that size was unprecedented.” There was some skepticism over the structure, he remembers. “It was stubbornness, I suppose, that kept me working in an area that wasn’t fashionable.”

Since then, Craik has discovered many other examples of the cyclotides, and that research has dovetailed nicely with his work on the peptides known as conotoxins. By linking the N- and C-termini of a conotoxin from cone snail venom, essentially transforming it into a cyclotide, Craik’s group has made a stable peptide with promising properties for treating chronic pain.

As for the Hirschmann prize, Craik says, “I’m just really honored and delighted to receive the award.”

Craik will present the award address before the ACS Division of Biological Chemistry.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter