Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Pipeline Pitfalls

Big pharma’s R&D revamping is hitting biotech company partners

by Michael McCoy

April 11, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 15

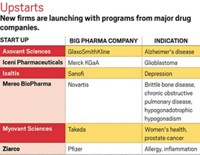

Research pipeline reassessment by big pharma companies is taking its toll on biotech industry partners. In recent weeks, at least three investigational medicines or programs have been dropped by big companies and returned to their partners. Although the biotechs involved are shrugging off the impact, the trend does not bode well for the industry.

Late last month, Merck & Co. returned all rights to betrixaban to Portola Pharmaceuticals. Betrixaban is a Factor Xa inhibitor anticoagulant being evaluated for the prevention of stroke in patients with a heart disorder known as atrial fibrillation.

The two companies had announced a collaboration and license agreement for the small-molecule drug in July 2009. Merck paid Portola an initial fee of $50 million and committed to making up to $420 million in additional payments, depending on milestone achievement. Merck also agreed to assume all development and commercialization costs, including the considerable price tag for Phase III clinical trials.

The companies had advanced betrixaban through Phase II trials when Merck announced its decision. “As part of an ongoing prioritization of our late-stage pipeline, we have decided to return rights for betrixaban to Portola,” stated Luciano Rossetti, Merck’s senior vice president for global scientific strategy. Portola, which is privately held, said it will work with its academic partners on an independent development plan to bring betrixaban to the market.

In February, Merck ended another partnership, this one still in the discovery phase. It returned rights to metabolic, cardiovascular, and inflammatory disease targets developed with Belgium-based Galapagos. Kathleen M. Metters, Merck’s senior vice president for external discovery and preclinical sciences, attributed the end of the alliance to “changes in our early discovery strategy” that “required us to make some challenging decisions.”

Another victim of portfolio reassessment was an alliance between GlaxoSmithKline and Targacept. Last month, the British firm announced the end of its pact with Targacept to discover drugs that target neuronal nicotinic receptors in five areas: pain, smoking cessation, addiction, obesity, and Parkinson’s disease. The decision came about a year after GSK revealed a research restructuring that included an exit from select neuroscience areas, including depression and pain.

In announcing the termination, J. Donald deBethizy, Targacept’s chief executive officer, sought to put a good spin on the turn of events. “While we are disappointed that we will be no longer working with our colleagues at GlaxoSmithKline, we are energized to have increased flexibility to apply our resources where emerging science dictates,” he said.

Interestingly, investors were unfazed by the news, and Targacept’s stock barely budged. Kimberly Lee, a stock analyst who covers Targacept for Global Hunter Securities, explains that the writing was on the wall for the GSK deal. “GSK had indicated last year that they would be reassessing their pipeline,” Lee says. “When they finally decided, it wasn’t a surprise to us.”

Lee doesn’t see the end of the deal as necessarily bad news for Targacept. She points out that it was a preclinical collaboration with no significant value yet to the company. As for funding the research in the future, she notes that Targacept has received grant support from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the National Institutes of Health. “The company may not need to seek a partner to replace GSK,” Lee says.

But the overall deal-dropping trend is disquieting, says Daphne Zohar, founder and managing partner of PureTech Ventures, a Boston-based private equity firm that invests in novel therapeutics, medical devices, diagnostics, and research technologies. “Unfortunately, I do think we’ll see this trend continuing,” she says. “Senior leaders at many large pharma companies are reassessing everything from fundamental approaches to drug discovery to specific portfolio priorities.”

Biotech companies on the losing end of a portfolio reassessment, she observes, have to deal with two issues: combating the perception that the cancellations stem from deficiencies in their drug programs and finding the money to continue the programs in a market where many alternative investors are strapped for cash.

“If they have sufficient capital to go it alone, then they may be okay,” Zohar says. “But given the liquidity deficit of many previously large venture funds, it will probably be a painful process—even if they can overcome the perception issue.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter