Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Chopping Up Lignin

Organic Chemistry: Catalyst selectively cleaves key bond in models of complex plant polymer

by Carmen Drahl

April 25, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 17

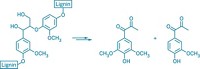

Using a nickel catalyst, chemists have found a way to break an aromatic ether bond while leaving the aromatic ring itself unscathed (Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1200437). The work provides proof of concept that metal catalysts could be used to convert lignin—a biopolymer that is replete with aromatic ether linkages and that lends stiffness to plants—into fuels or commercial chemicals.

Lignin gums up some chemical processes for obtaining energy from other plant components such as cellulose. And although it can be burned to provide heat and energy, it’s a solid that is tough to transport, says organometallic chemist John F. Hartwig of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. “It would be nice to be able to chop it up into small enough pieces to make it a liquid” suitable for processing into transportation fuels or aromatic chemical feedstocks, he says.

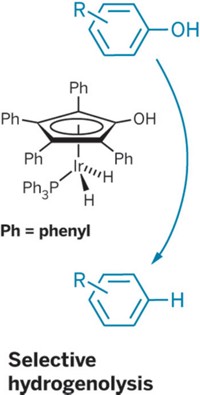

But enzymes have trouble breaking down lignin, and chemically cleaving aromatic ether bonds such as those in lignin is messy, requiring harsh conditions and leading to mixtures of products, some with reduced aromatic rings. Using hydrogen and a new nickel catalyst, Hartwig and postdoctoral researcher Alexey G. Sergeev selectively cleaved aromatic C–O bonds in lignin model compounds. So far, the method requires relatively high amounts of the catalyst and a strong base, but Hartwig says his team, which is among several Illinois research groups in the BP-supported Energy Biosciences Institute, is working to eliminate those drawbacks. He has filed a provisional patent application on the process.

“There’s a saying that you can make anything you want to from lignin except for money,” says George W. Huber, an expert in biomass conversion at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Researchers have been trying to break down lignin for a long time, but selectivity has always been an issue, he says. The catalyst must be improved to work cost-effectively on lignin itself, but “this route shows that selective lignin depolymerization chemistry is possible,” he says. “It shows the power of modern chemistry for solving energy problems.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter