Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

A New Look At Protein Misfolding

Protein Chemistry: Fluorescence method reveals details of disease-related process

by Celia Henry Arnaud

June 6, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 23

Researchers have used an established fluorescence technique to study misfolded structures that arise in multidomain proteins (Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature10099). Most studies of protein misfolding have focused on single-domain proteins, but the majority of eukaryotic proteins are multidomain.

Diseases such as Alzheimer’s may be caused by a gradual accumulation of such multidomain misfolding events. The fluorescence method and the finding it uncovers could thus lead to a better understanding of protein misfolding diseases, and of protein evolution.

The study shows that “we’re now able to use single-molecule methods to see important rare events that happen in proteins,” Jane Clarke of Cambridge University says.

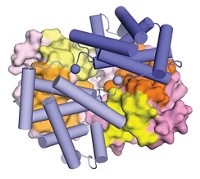

In the study, Clarke and coworkers, in conjunction with Benjamin Schuler’s lab at the University of Zurich, use single-molecule FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) to distinguish between correctly and incorrectly folded forms of multidomain proteins made of repeating domains from the muscle protein titin.

They label each protein with a pair of FRET donor and acceptor dyes. In two-domain proteins, each domain contains one dye. In three-domain proteins, only the first and third are labeled.

The FRET efficiency (the fraction of donor excitation that results in acceptor fluorescence) increases when dyes get closer to one another and reveals the folding state of labeled proteins. High efficiency means the protein misfolded, swapping strands between domains so the dyes are close to one another. In correctly folded proteins, the dyes are farther apart and the FRET efficiency is correspondingly lower.

The researchers constructed proteins with various domains from titin, a large protein containing hundreds of domains. They found that the construct with two identical domains misfolds about 5% of the time, and their simulations suggest that the domains swap strands. But misfolding doesn’t occur if the two domains have sufficiently dissimilar sequences. The three-domain protein forms two types of misfolded structures—one in which an end domain swaps strands with the unlabeled central domain and another in which the two end domains swap strands.

The researchers were surprised to find that the misfolded species have long lifetimes, on the order of several days. “Our back-of-the-envelope picture of what they look like had them living for hours, not days,” Clarke says.

The most surprising aspect of the paper “is the substantial kinetic stability of the misfolded domain-swapped structures,” says Jeffery W. Kelly, a protein-folding expert at Scripps Research Institute. He wonders whether the misfolded forms will be as common and as stable under physiological conditions as they are in buffer.

“Many human proteins contain repeats of the same kind of domain,” Clarke says. “Evolution has had to make sure that you can’t get long-lived misfolded species, which would cause a problem for the biology.” Ongoing studies hope to discover how evolution has avoided such problems.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter