Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Bioplastics Gathering

At the first BioPlastek forum, delegates met for an exchange of information and pointed discussion

by Alexander H Tullo

July 11, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 28

Two camps are emerging in the biobased plastics industry. Some companies are focusing on new-to-the-world polymers such as polylactic acid. Others are sticking with the stable of traditional plastics, but harnessing biology to derive “drop-in” substitutes for p-xylene and other petrochemical raw materials.

Representatives from both sides of the divide spoke two weeks ago at the 2011 BioPlastek Forum at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City. Lively debate spilled from the presentations and into question-and-answer sessions.

This is precisely the kind of discussion that Ronald S. Schotland, president of event organizer Schotland Business Research, wanted to provoke with the first BioPlastek Forum. The gathering brought together representatives from major polymer users and start-up firms trying to develop new biobased materials. “We need to bring together all elements of the bioplastic chain in order to foster discussion,” Schotland said.

At the event, executives from brand owners such as H. J. Heinz, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Ford Motor Co. said they were open to new-to-the-world materials and have even been testing them. But they also need materials that meet their specifications and work well in their existing manufacturing and recycling infrastructure.

The keynote speech at the event was given by Michael O. Okoroafor, vice president of packaging R&D and innovation at Heinz, which was a sponsor of the event along with Coke and the Chemical Development & Marketing Association. Okoroafor profiled Heinz’s partnership with Coke for the PlantBottle.

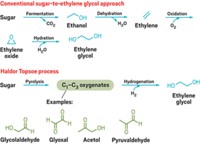

The initiative is decidedly in the “drop-in” category. The PlantBottle is made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in which the ethylene glycol monomer is derived from ethanol instead of petroleum, giving the bottle roughly 30% biomass content. Coke introduced the bottle in 2009. Heinz is currently rolling out ketchup bottles using the polymer.

For Heinz, the benefits of using the bottles are an 8 to 14% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, performance and recyclability identical to those of conventional PET, and the ability to get to market quickly. “You can eat ketchup from the PlantBottle this afternoon,” Okoroafor said, referencing a reception after the presentation where sliders and ketchup were served.

Okoroafor shared the podium with Scott Vitters, general manager of Coke’s PlantBottle Packaging Platform. Vitters said the company spent a year experimenting with various biobased plastics, but none of them performed as well as PET. “Comparing other materials to PET reminded us of the performance that we were getting,” he said.

Vitters hopes eventually to debut a 100% bio-content bottle. It would require a biobased route to PET’s other monomer, purified terephthalic acid (PTA), which in turn is derived from p-xylene.

Denise Lefebvre, vice president of global beverage packaging for Pepsi, spoke after Vitters. Pepsi has an even more ambitious plan: to pilot 100% renewable PET bottles by 2012. Moreover, the company aims to use agricultural waste as the feedstock. But when asked by the audience about the company’s plans for biobased PTA, Lefebvre declined to give more details. “We are not going to be disclosing that information at this time,” she said.

The forum held no shortage of start-up firms that would be happy to oblige Coke and Pepsi with their biobased routes to p-xylene or PTA. One was Anellotech, which uses a catalytic process developed by George W. Huber, professor of chemical engineering at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, to make a stream of benzene, toluene, xylenes, and olefins from biomass.

Anellotech’s chief executive officer, David Sudolsky, told attendees that the company plans to be running a demonstration plant by the end of 2012 that will process 2 metric tons per day of feedstock into a half ton of product. He claimed that the process can already make aromatics more cheaply than petrochemical plants can. Plans call for a 250-metric-ton-per-day commercial plant by 2015.

Another start-up at the meeting, Virent Energy Systems, discussed its BioForming process, which partially deoxygenates and then reforms sugar. The result is a blend of hydrocarbons that is similar to the petroleum reformate that yields gasoline and aromatic streams at refineries. The company recently announced that it had obtained p-xylene from the process.

“We have known for a long time we could make p-xylene,” said Kieran Furlong, commercial manager for chemicals at Virent. “To prove it to the world, we separated it and purified it.” The company runs a pilot plant in Madison, Wis., that can make 10,000 gal per year of bio-reformate. It aims to have a commercial plant by 2015.

Draths Corp. presented a route to PTA. The company uses fermentation to make muconic acid, which can then be a starting point for chemicals including PTA, caprolactam, caprolactone, and adipic acid.

The company plans to offer sample quantities of PTA by the end of this year, said Allen Julian, head of market development. Draths wants to have a 50,000-metric-ton demonstration unit running by 2014 and a commercial plant with up to 500,000 metric tons of capacity sometime later. The firm’s route to the nylon 6 intermediate caprolactam is a little further along. Draths plans a pilot plant with thousands of tons of capacity next year.

Julian claimed to be unfazed by the number of companies with sights set on p-xylene, PTA, and other big-volume chemicals. “The market is so big for some of these products that no company will be the clear winner,” he said.

While many presenters emphasized that working with proven commodities eliminates marketing uncertainties, others stressed recycling. Breck Speed, CEO of water bottler Mountain Valley Spring, noted that launching brand-new biopolymers in the name of going green might have unintended environmental consequences. “People should do nothing to upset the recycling stream that exists now,” he said. He went on to praise Coke and Pepsi for “reading the tea leaves and understanding what needs to be done.”

Richard A. Gross, professor of chemical and biological sciences at the Polytechnic Institute of New York University, took the microphone during the question-and-answer session following Speed’s talk. He acknowledged that “drop-ins” can leverage existing infrastructure but said new polymers present other opportunities. “With bio-building blocks, you will come up with improved functionality and improved materials,” he said. “It is just a matter of time.”

At BioPlastek, several companies offered new-to-the-world materials. One was SyntheZyme, which was founded on technology developed by Gross at NYU-Poly.

The company uses genetically modified Candida tropicalis yeast to convert triglycerides and sugar feedstocks into ω-hydroxy fatty acid monomers. SyntheZyme polymerizes them in a polycondensation reaction using a titanium catalyst. The resulting polymer, said CEO Guy Penard, has ductility and other properties somewhere between high-density and low-density polyethylene. He suggested it might be blended with polylactic acid to make up for shortcomings in that polymer’s properties. “We believe that we fill a gap in the existing application range,” he said.

Avantium CEO Tom van Aken gave a talk on a catalytic technology his company developed to turn sugar into furan dicarboxylic acid (FDCA), which can be reacted with ethylene glycol to make a polyester called polyethylene furanoate (PEF). The target application is beverage bottles. The plastic, he said, boasts an oxygen barrier six times greater than PET’s. “If you are looking at products that are sensitive to oxygen, this is a major step forward,” he said.

The Avantium CEO was also critical of drop-ins. “Drop-in substitutes have one big disadvantage,” he said. “There is only one thing that they can compete on, and that is price.”

After van Aken’s talk, Mountain Valley Spring’s Speed pressed him on PEF, noting that the oxygen barrier wouldn’t be necessary for products such as water and that a new recycling infrastructure would be required to accommodate the material.

“Many people have a broader view of this and are looking for enhanced materials,” van Aken re sponded.

A telling point on the debate was made in a talk near BioPlastek’s close by William L. Tittle, director of strategy at the chemical consulting firm Nexant. He observed that NatureWorks, the Cargill unit that was one of the first to bring a new biobased polymer to market with polylactic acid, needed eight years to utilize all of its plant capacity. Braskem, which makes polyethylene from ethanol in Brazil in a similarly sized plant, sold out its capacity in three months. ◾

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter