Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Electronic Chemicals

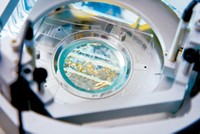

Behind the scenes, materials suppliers help make electronics faster, brighter, smaller, cheaper

by Jean-François Tremblay

July 11, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 28

Pushing the limits of the feasible is standard in the electronics industry. Apple’s iPhone has more processing power than desktop computers did a mere 10 years ago. Relatively cheap products like the Amazon Kindle can hold a library of books. Flat-screen televisions are now larger and more brilliant than ever, yet consume less power.

COVER STORY

Electronic Chemicals

Better components enable the development of popular consumer items. And performance materials provided by chemical companies, in turn, enable the manufacture of these components.

Even worse, materials makers don’t even know what types of memory chips their clients will be producing in 2015. As the first story in this package explains, DRAM and flash memory will still be industry mainstays. But other chip architectures are poised to enter the mainstream, primarily due to the mounting challenge of making DRAM circuitry ever smaller.

Shrinking the circuitry of microchips presents difficulties in lithography. Semiconductor industry participants are generally surprised by how much mileage they have squeezed out of 193-nm lithography, which they had expected would be outdated by now. The second story details how materials suppliers have helped extend 193-nm lithography and how they are preparing for the next generation of lithography based on extreme ultraviolet light.

The future seems clearer for materials companies that supply the light-emitting diode industry. Adoption of LED lighting devices has enjoyed several growth spurts, starting with cell phones and laptops, moving to televisions, and now emerging in residential applications. The third story chronicles the scramble by materials companies to ramp up supply of trimethylgallium, which is needed to create the semiconductor at the heart of a white LED.

The electronic materials market is fast paced and potentially very profitable, but it is not for the faint of heart. Spending precious research dollars on new materials that may or may not be adopted is enough to keep any R&D director up at night.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter