Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

New Life For Free-Trade Deals

Republicans, Democrats may come together to pass a trio of long-delayed agreements

September 26, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 39

Business groups are increasingly optimistic that Congress will soon approve three stalled free-trade agreements as part of a renewed effort by policymakers to reinvigorate the manufacturing sector and spur job creation.

Capitol Hill observers expect that a series of votes on related tariff and trade issues in the coming weeks will clear the way for ratification—perhaps before the end of October—of the deals the U.S. has negotiated with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea.

“We are confident that we will get this done,” said John G. Murphy, vice president of international affairs at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, at a Sept. 8 briefing on the organization’s push to get the pending free-trade agreements through Congress.

In addition to intensifying its congressional and grassroots lobbying effort, the chamber is also using an advertising campaign to convince lawmakers to vote for the three trade pacts, Murphy said.

The chamber has targeted the massive 85-member House of Representatives Republican freshman class, many of whom expressed strong reservations about the trade deals on the campaign trail last year. The nation’s biggest business lobby has held dozens of events in these representatives’ home districts to build support.

U.S. manufacturers currently export a total of more than $48 billion worth of goods annually to Colombia, Panama, and South Korea. The U.S. International Trade Commission estimates that the three trade agreements combined could boost U.S. exports by $12 billion a year and potentially create 100,000 new jobs at a time of stubbornly high unemployment.

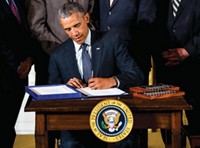

In his speech before a joint session of Congress earlier this month, President Barack Obama cited the trade pacts he inherited from the George W. Bush Administration as a significant component of his job-creation plan.

“Now it’s time to clear the way for a series of trade agreements that would make it easier for American companies to sell their products in Panama and Colombia and South Korea, while also helping the workers whose jobs have been affected by global competition,” Obama said. “I want to see more products sold around the world stamped with the three proud words, ‘Made in America.’ That’s what we need to get done.”

All three trade deals were signed more than four years ago, but they were never submitted to Congress for ratification. During Obama’s first two years in office, his Administration renegotiated certain provisions and added side agreements in an attempt to increase support for the pacts among Democrats and lessen opposition by organized labor.

But the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest union federation, continues to oppose the trade pacts, arguing that they will lead to a further decline in U.S. manufacturing as jobs are outsourced overseas. The organization, which has strong historic ties to the Democratic Party, has been particularly critical of the pact with Colombia, charging that the country hasn’t done enough to stop antiunion violence and improve its labor and human rights record.

“This is the wrong time to put at risk good jobs in our manufacturing sector,” says Thea M. Lee, the AFL-CIO’s deputy chief of staff.

With many Democrats skeptical of expanded trade, the White House has held off on sending the trade accords to Capitol Hill until House Republicans provide assurance that funding for a lapsed worker-assistance program will be renewed—a demand urgently sought by Obama’s union backers.

In early August, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) announced that they had agreed on a deal that will allow votes on a scaled-back version of the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program and then the three trade pacts.

“I do not support movement on the free-trade agreements, which I have never supported, until TAA has passed,” Reid said. The nearly 50-year-old program provides health and unemployment benefits and retraining for workers who have lost their jobs because of foreign competition. It expired in February.

House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) has promised to allow a vote on retroactively reauthorizing the worker aid program “in tandem” with the “job-creating trade bills.” But U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk told reporters on Sept. 12 that details still must be worked out on the House side regarding the sequencing of votes. “We’re continuing to work so we can get TAA done and move forward with the free-trade agreements,” said Kirk, the Administration’s top trade official.

In the first step toward eventual passage of the trade deals, the House agreed by voice vote on Sept. 7 to renew another expired trade program—the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP)—which allows mostly raw materials and certain other goods from 129 developing nations to enter the U.S. duty-free.

Under a carefully orchestrated plan, the Senate now intends to use the House-passed GSP bill (H.R. 2832) as a vehicle to reauthorize the TAA program. The upper chamber would then send the combined GSP/TAA measure back to the House for passage along with the free-trade agreements.

At a Sept. 13 news briefing, Reid said that once the House passes the GSP/TAA legislation, he will allow votes on the three pending trade pacts because they enjoy bipartisan support, even though he personally opposes them.

The free-trade agreements are strongly supported by the chemical industry, which annually ranks as one of the nation’s leading exporters. U.S.-based chemical companies shipped $171 billion worth of products abroad in 2010, accounting for more than 10 cents out of every dollar in U.S. exports.

“American jobs depend on access to important markets, and the free-trade agreements will ensure that access and strengthen our industry’s competitiveness and job creation,” says Calvin M. Dooley, president and chief executive officer of the American Chemistry Council, a trade group representing more than 140 U.S. chemical manufacturers.

“The global market for chemistry is intensely competitive, and the protections of a solid free-trade agreement can mean the difference between market success and failure,” Dooley adds. “Our members are eager to see the free-trade agreements approved and implemented.”

Under the accord with South Korea—the seventh-largest market for U.S. chemical exports—almost 95% of bilateral trade in consumer and industrial products would become duty-free within three years, and most of the remaining tariffs would be phased out within a decade, according to the Commerce Department’s International Trade Administration (ITA).

Over half of U.S. chemical exports to South Korea would receive duty-free treatment as soon as the agreement takes effect, ITA reports; tariffs on an additional one-third of U.S. chemical export shipments would be eliminated within three years.

The deal with Colombia, one of the largest economies in Latin America, would end tariffs on 86% of U.S. chemical exports immediately and phase out the rest within 10 years, according to ITA. The accord with Panama is similarly structured, ITA says.

“The benefits to chemical manufacturers as a result of approving free-trade agreements are real,” says Lawrence D. Sloan, president and CEO of the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates (SOCMA), which represents mostly small and medium-sized batch and specialty chemical makers in the U.S.

As an example, Sloan notes that the chemical industry paid $480 million in duties to Colombia between 2008 and 2010. Colombian chemical tariffs currently average 7.6% and range as high as 20%. “Clearly, this pending free-trade agreement will bring immediate relief to chemical manufacturing companies, allowing them to expand sales to this important market,” he remarks.

Industry leaders say the long delay in ratifying the three trade deals is costing the U.S. crucial market share to the European Union, Canada, China, and others. A free-trade agreement between the EU and South Korea took effect in July, while Colombia and Canada launched a bilateral trade pact in August. China has also begun to make inroads into Latin America, replacing the U.S. as the top trading partner with several South American nations.

“Each day Congress prolongs a vote on these agreements, the more we cede the advantage to foreign manufacturers and further exacerbate the fragile state of the U.S. economy, at a time when we can least afford it,” Sloan says.

However, the chemical industry is optimistic that Congress will ratify the three free-trade deals soon. “Members of Congress in both parties and in each chamber are saying the right things. That makes us confident that they’ll come together and get this done,” says Justine Freisleben, a manager on SOCMA’s government relations staff.

“Although these scenarios are a somewhat complicated series of votes, together, they accomplish the objective of the White House, which is passing TAA before the trade agreements, and also the goal of key leaders in Congress, which is to get these long-stalled agreements moving,” Freisleben tells C&EN.

The trade pacts, she adds, will have a positive impact on U.S. industry, especially chemical manufacturing, for years to come. “With greater certainty, businesses will be more likely to hire additional workers to meet either current needs or growing demand,” Freisleben says. ◾

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter