Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

Making Dinitrogen

Environment: Pathway involves microbial oxidation of ammonia via nitric oxide and hydrazine

by Jyllian Kemsley

October 10, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 41

The mechanics of a key biogeochemical reaction that affects atmospheric chemistry have been identified by an international research group. The research shows how one of two major routes for putting dinitrogen into the atmosphere happens via a microbiological process known as anammox, for anaerobic ammonium oxidation.

In the new work, Boran Kartal of the Netherlands’ Radboud University Nijmegen and colleagues demonstrate that microbes turn ammonium into dinitrogen anaerobically through a pathway that involves the intermediates nitric oxide and hydrazine (Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature10453).

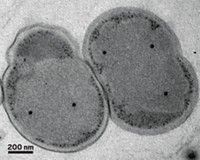

To pin down the reaction sequence, Kartal and colleagues worked with the bacterium Kuenenia stuttgartiensis. They grew the microbe in a bioreactor and studied which genes the microbe transcribed, which enzymes it made, and the activity of those enzymes.

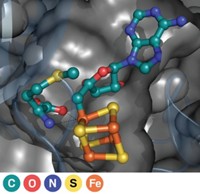

Kartal and colleagues found that K. stuttgartiensis first uses a reductase enzyme to convert NO2– to NO. Then a three-protein hydrazine synthase complex combines NO and NH4+ to form N2H4. Finally, a hydrazine dehydrogenase enzyme converts N2H4 to N2. The electrons for the first two steps of the process come from the final oxidation of N2H4 to N2.

Scientists used to think that N2 in the atmosphere came only from denitrification, or reduction of NO3– to N2. But about 15 years ago, anammox came to light, and now researchers believe that as much as half of atmospheric N2 comes from that process, says Daniel J. Arp, a professor of botany and plant pathology at Oregon State University. Anammox is also of interest as a way to remove nitrogen from wastewater streams.

Although there was some evidence that allowed researchers to guess at the mechanics of the anammox process,“there was not a fully integrated pathway with supporting evidence for each step,” Arp says. The new work provides that complete pathway. Arp was not involved in the research.

Arp is particularly excited to learn more about the hydrazine synthase complex that Kartal and coworkers discovered. “It will be fascinating to learn about the mechanism” of hydrazine formation and what intermediates are formed, how electrons are transferred, and which metals may be involved, he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter