Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Probing Chemical Timekeeping

Scientists find a new role for posttranslational modification in circadian rhythms

by Sarah Everts

January 31, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 5

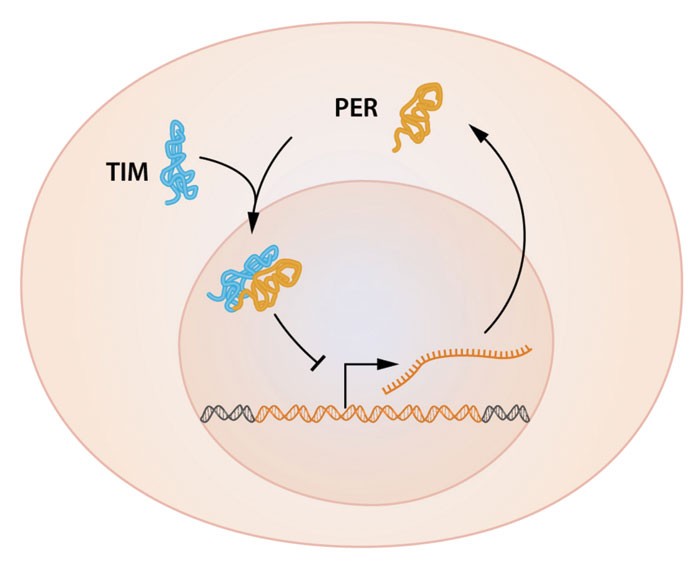

Our internal clocks may be a pain for frequent flyers dealing with jet lag, but the timekeeping helps us regulate metabolism so that we efficiently use energy when we are awake or asleep. Researchers based in the U.K. and France now report that such cellular timekeeping—also known as circadian rhythms—involves a previously unknown cycle of posttranslational modifications, in addition to the transcription of a well-known handful of clock genes. Better understanding of circadian rhythms may help scientists optimize the efficiency of cellular metabolism and allow them to, for example, engineer better biofuel-producing algae and monitor metabolic diseases such as diabetes. According to Akhilesh B. Reddy of the University of Cambridge, Andrew J. Millar of the University of Edinburgh, and coworkers, cellular timekeeping involves a repetitive sequence of oxidations and reductions of a cysteine thiol on a peroxiredoxin protein (Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature09654; DOI: 10.1038/nature09702). The team showed that circadian rhythms are maintained without transcription in red blood cells—which don’t have a nucleus and therefore can’t transcribe—and in a model alga in which transcription had been turned off with a chemical inhibitor. “The research is provocative and inventive,” says Joseph T. Bass, a medical researcher at Northwestern University. “The work opens up new questions concerning the origins and functions of molecular clocks.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter