Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Sludge Sloughs Off Perfluorinated Chemicals

Toxic Substances: Biosolids can leach perfluorinated chemicals into farm soil, albeit at low levels

by Rebecca Renner

April 8, 2011

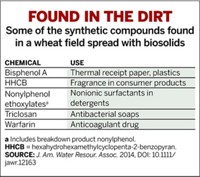

Farmers often add nutrients to their fields in the form of treated sewage sludge, also called biosolids. Environmental scientists worry that chemical contaminants—in particular perfluorochemicals—in these biosolids could leach into the soil and eventually enter groundwater. In the first rigorous field study of how perfluorochemicals could leach from biosolids, researchers have found relatively low levels of the chemicals in soils treated with urban sewage sludge (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es103903d).

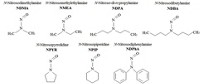

Many consumer products, such as clothing and food wrappers, use perfluorochemicals as stain- or grease-resistant coatings. These chemicals get into household wastewater and eventually reach sewage systems. The contaminants are persistent and studies have linked them to reproductive and developmental problems in animals.

In 2008, scientists from the Environmental Protection Agency studying fields in Decatur, Ala., measured some of the highest concentrations of perfluorochemicals ever recorded in U.S. soils. They also found perfluorochemicals in groundwater, grass, and cattle that grazed nearby. The Decatur findings raised the possibility that sludge applied to farm soils could contaminate groundwater, says chemist George O'Connor of the University of Florida.

But Decatur's municipal sludge contained industrial waste, so its levels of perfluorochemicals were greater than most biosolids' levels, O'Connor adds.

To study a more average system, chemist Chistopher Higgins of the Colorado School of Mines, and his colleagues analyzed Chicago biosolids. Higgins and his team measured perfluorochemicals in samples of biosolids and soil from fields treated with biosolids for more than 30 years, which had been performed by The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago.

In the fields, trace amounts of perflurochemicals penetrated almost 4 feet below the surface. At this depth, higher levels of the chemicals could lead to groundwater contamination from leaching. Longer chain perfluorochemicals leached more slowly than shorter chain chemicals did, which confirmed results of laboratory experiments. However, one common pollutant, perfluorooctanoic sulfonate, leached less than theoretical studies had predicted. Higgins says that perfluorochemical behavior in biosolids-amended soils is more complex than previously thought.

According to chemist Jennifer Field of Oregon State University, the study addresses a major knowledge gap in perfluorochemical research: whether the contaminants move from biosolids to agricultural soils. But the study doesn't address all perfluorochemicals, she notes, such as ones used on food wrappers.

Although the levels of perfluorochemical leaching in Chicago are too low to affect groundwater, Higgins won't rule out biosolids as a possible source of contamination. The question remains: How typical are Chicago's biosolids and farm soils? "We certainly need to look at other biosolids and other soils," he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter